1949 is often cited as the end of the commercial sailing era, when a ship called Pamir rounded Cape Horn — the maritime route between the Atlantic and Pacific oceans — for the last time. Coal and oil-fueled ships gradually overtook wind during the the 19th and early 20th centuries due to their speed, reliability, and smaller crew needs. But until then, it was primarily wind that carried cargo around the world.

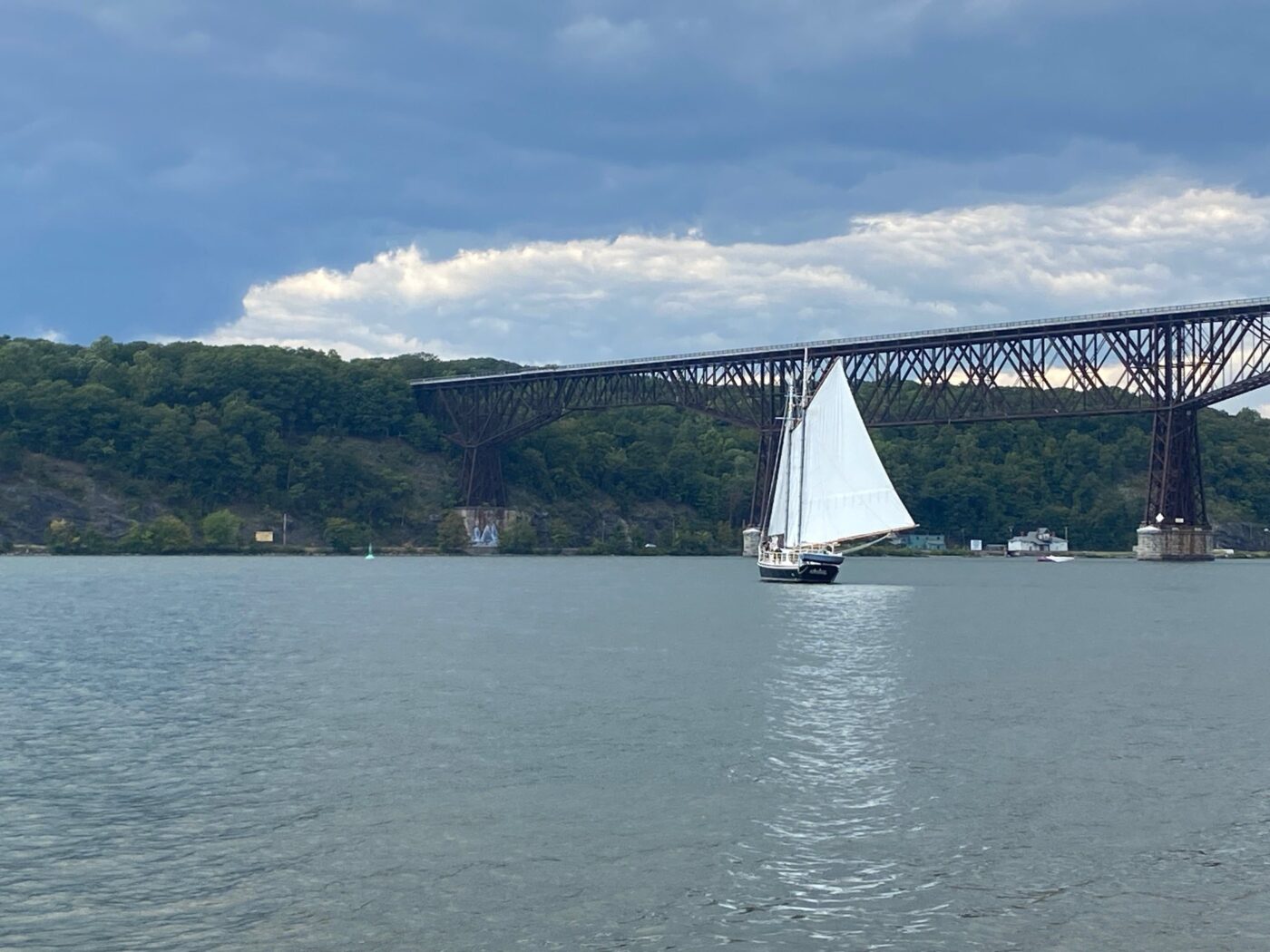

Which is why, when Hudson Valley’s Schooner Apollonia rolls into the dock carrying coffee, maple syrup, and other local goods after a voyage down the river, the scene feels nostalgic, even comforting, in an age of hyper-efficiency and digitization. The carbon-neutral vessel is in its sixth year of trying to revive wind-powered shipping up and down the Hudson River.

“The Hudson River has become this kind of universal backdrop for people these days,” says Apollonia captain Sam Merrett. “But the idea that it actually connects us, that it moves stuff along it, reminds you that it’s a living waterway you can interact with.”

The first wind-powered vessel to transport cargo along the East Coast in decades, the Apollonia has completed 22 cargo runs between Hudson and New York Harbor since its maiden voyage in 2020.

While other initiatives have brought attention to reviving local waterways and infrastructure, the Apollonia continues to be the only operation that actually transports cargo via sail in the U.S.

How come? Is the current moment of two-day shipping to blame? Merrett faults tricky overall financials rather than consumer expectations for super-short shipping times per se.

“The economics of moving cargo on the river are really tricky,” says Merrett. “But the more of us that do it, the more practical it becomes. The more vessels there are going up and down the river, the more it makes sense to have a dock in your town.”

Many of the river’s working docks have withered throughout their inactive years, and waterfronts need investment before smaller cargo vessels can truly return at scale.

The Apollonia turns to other streams of income beyond cargo to support its operation, which Merrett says is a must in the current industry. The crew receives funding from public programming, philanthropic support, and occasional corporate sponsorships.

“To make it economically viable, it does need to have this fun cultural component,” says Merrett. While that may make others apprehensive to adopt sail freight, he sees as an opportunity. “People say, ‘Oh, to sail cargo we’d have to do waterfront education.’ And I’m like, ‘Cool! We get to sail cargo and do education.’”

The team even partnered with Grain de Sail II, one of the world’s largest modern cargo sailboats, to bring Hudson Valley goods across the Atlantic Ocean, back to the ship’s home port in France.

There are many reasons to advocate for a wind cargo renaissance — one being that a recent report suggests that to hit the global shipping industry’s net-zero emissions goal by 2050, both massive volumes of hydrogen-based fuels and wind power will be necessary.

Unfortunately, “the total emissions from shipping are currently still creeping upwards,” according to Gavin Allwright, secretary of the International Windship Association. “But if you look at them through a cargo-moved-per-mile lens, the drift is downwards. So it’s becoming more efficient, but our demands on shipping are growing.”

This is exactly the reason why the Apollonia hopes to inspire a broader shift than just a one-to-one tradeoff of commercial shipping to wind. That change in itself doesn’t address the realities of our cultural expectations around the speed of shipping.

For the Apollonia, the shift is far more about reconnecting communities to their waterways than just offering a low-emissions solution to an environmental-cultural problem. So the fact that transportation takes longer than it would by truck or commercial ship isn’t a drawback — it’s part of the point.

The team also knows that people aren’t going to be quick to pay a premium for products that take longer to arrive. That’s why they’re committed to keeping prices comparable to truck-transported goods — a cost that is compensated for through their other streams of income.

And of course, environmental benefits are a necessary outcome of this cultural change.

Allwright says retrofitting conventional vessels to support wind assistance could create significant fossil fuel savings near-term. Over time, a network of “primary wind” ships (vessels designed to use sails first and motors second) can offer more prolonged impact.

“The big shipping companies are certainly embracing alternative fuels, but not as much wind as we’d like to see,” says Allwright. “Existing ships can be run far more efficiently with wind propulsion retrofits, probably with a 20-30% reduction in demand. And that’s for the very large ships that are burning fossil or alternative fuels.”

According to Allwright, the upfront investment is a major deterrent to adoption of wind. “We have a trend developing in the primary wind sector, which the Apollonia definitely fits into,” he says. “That segment is growing, but it’s taking longer. Of course, if we take the total cost over the lifetime of the vessel, it’s a lot cheaper. Your upfront expenditure is repaid over about 10 years, and then you’re basically operating with a free energy source.”

Allwright imagines a complementary future: hundreds of wind-assisted large ships and dozens of cooperating small wind vessels forming interconnected freight networks, revitalizing waterways as the networks develop.

Until then, the Apollonia offers a glimpse of what’s possible, where slower doesn’t just mean less carbon. It also means a richer connection to waterways and communities — an outcome that’s sustainable on every level.