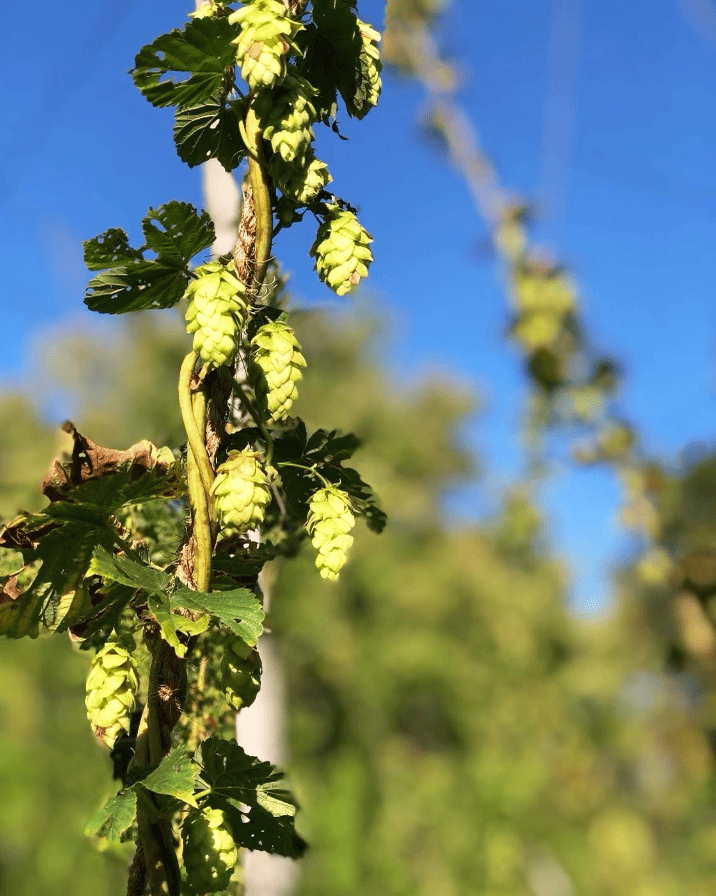

Hops are little pine-shaped powerhouses. You may not even recognize them when you see them, but the flowers of the hop plant (Humulus lupulus) provide flavor and aroma to beer. Brewers use more than 100 commercial varieties, selecting for factors like floral taste, bitter flavor, and citrusy aroma.

The plant was probably domesticated in China, but the first record in written history comes from Benedictine monks brewing beer in the 8th century in Munich, Germany. Renowned Brooklyn Brewery brewmaster Garrett Oliver explains that beers used to feature different species of plants for flavor. However, hops became the primary source of flavor since they have properties that delay bacterial growth (the more hops in a beer, the longer its shelf life will be).

Today, most hops used in the United States are grown in the Pacific Northwest, but in the 19th century, New York State was the epicenter of hop production. Billions of flowers were grown, harvested, treated and exported to beer makers across the nation through railways and the Erie Canal. Flash forward to today, though, and just about 300 acres of hops were grown in the entire state in 2022. For perspective, that’s an area smaller than half of Central Park in New York City. That same year, 43,000 acres of apple orchards were harvested.

Larry Smart is a professor in the horticulture section in the School of Integrative Plant Science at Cornell Agritech in Geneva, N.Y. For the last 25 years, he has been working with emerging crops, finding ways to showcase hops’ uses and economic benefits. Despite their history, hops are still considered an emerging crop in New York State because of the small production scale.

Smart explains that hops are notably a hard crop to grow and produce. First, the installation of a hop yard is costly. Hop bines — yes, they’re called “bines” rather than vines — are planted in rows. The bines grow vertically and must be support by the help of poles and cables. The setup requires specialized equipment to maintain and harvest the flower, Smart says. This is an initial barrier for new growers to invest in the product.

Additionally, they are very susceptible to several fungal diseases. “If you have a bad disease year, then the whole crop is wiped out,” Smart adds. He and his colleagues aim to grow varieties that will be more resistant to diseases and grow successfully in New York State.

This disease pressure led the industry to move hop production to the Pacific Northwest at the beginning of the 20th century, where the weather benefited large-scale production. In New York, Prohibition was the final nail in the industry’s coffin.

For the nearly century since Prohibition ended, there’s been an interest in improving hops knowledge and varieties at Cornell. In the archives at Cornell Agritech, Smart found a report from a research project from 1934 which aimed to determine the most suitable hop varieties for growing in New York and to propagate and improve desirable and disease-resistant varieties.

The state does have a nonprofit group that advocates for the growth of hops here. Adam Kreider is the executive director of that organization, the Hop Growers of New York. He says that after the Farm Brewery Law, which aimed to increase demand for locally-grown products and support the growing brewing industry in the state, passed in 2013, there was a massive spike in “upstart and new growers.” Yet in Kreider’s experience, the most successful growers are not the first generation, but those that have been growing for several generations.

“I would say if you want to start growing hops and to be profitable, it probably requires a minimal $250,000 to $500,000 initial investment,” says Kreider. Once hops are harvested, they must be treated correctly (after harvesting, the flowers have to be squeezed down and turned into pellets) and stored correctly. A “long mindset” is needed to grow a profit, Kreider says.

Long-term profits present many challenges, but the support from the state government on revitalizing the industry has been “very inspiring,” says Kreider. Additionally, there are distinct advantages to producing a commercial crop in New York State. For example, he argues that New York has a “big advantage on carbon footprint and cost of export to Europe” in comparison to the West Coast hops.

Smart believes that the most important thing for growers is to be “judicious” in choosing varieties, as they have to consider flavors and aromas attractive to brewers and consumers who are interested in buying locally.

“We also realized during the pandemic how fragile our agricultural supply chains are,” says Smart. He argues that growing hops in the state will benefit local growers and consumers, but diversifying the growing regions across the country can provide an essential buffer to failures in the supply chain.