Long before bagels or pizza, New York City was famous for its oysters. Best served fresh from the nearby bays and waterways, these oysters were mostly a local cuisine. But that changed when the Erie Canal was completed in October of 1825, reducing the six-week journey from Albany to Buffalo by land to just six days by water. Oysters suddenly became a hit in Buffalo and beyond.

This small piece of history illustrates how the Erie Canal was a path to otherwise impossible opportunities for New York State and the wider world. As the 200-year anniversary of the canal’s completion is marked in October 2025, it’s worth reflecting on how the canal changed economies, communities, and also ecology along its 363-mile path from Lake Erie to the Hudson River.

A Historic Impact on Communities Big and Small

As more goods flowed through the Erie Canal to inland America, immigrant workers flowed into the cities and towns along its path. New York City’s population boomed. Buffalo, Rochester, and Syracuse also quadrupled between 1830 and 1850, and more than 200 other communities along the canal and the Hudson River similarly grew or emerged. Today, 80% of Upstate New York’s population still lives within 25 miles of the Erie Canal.

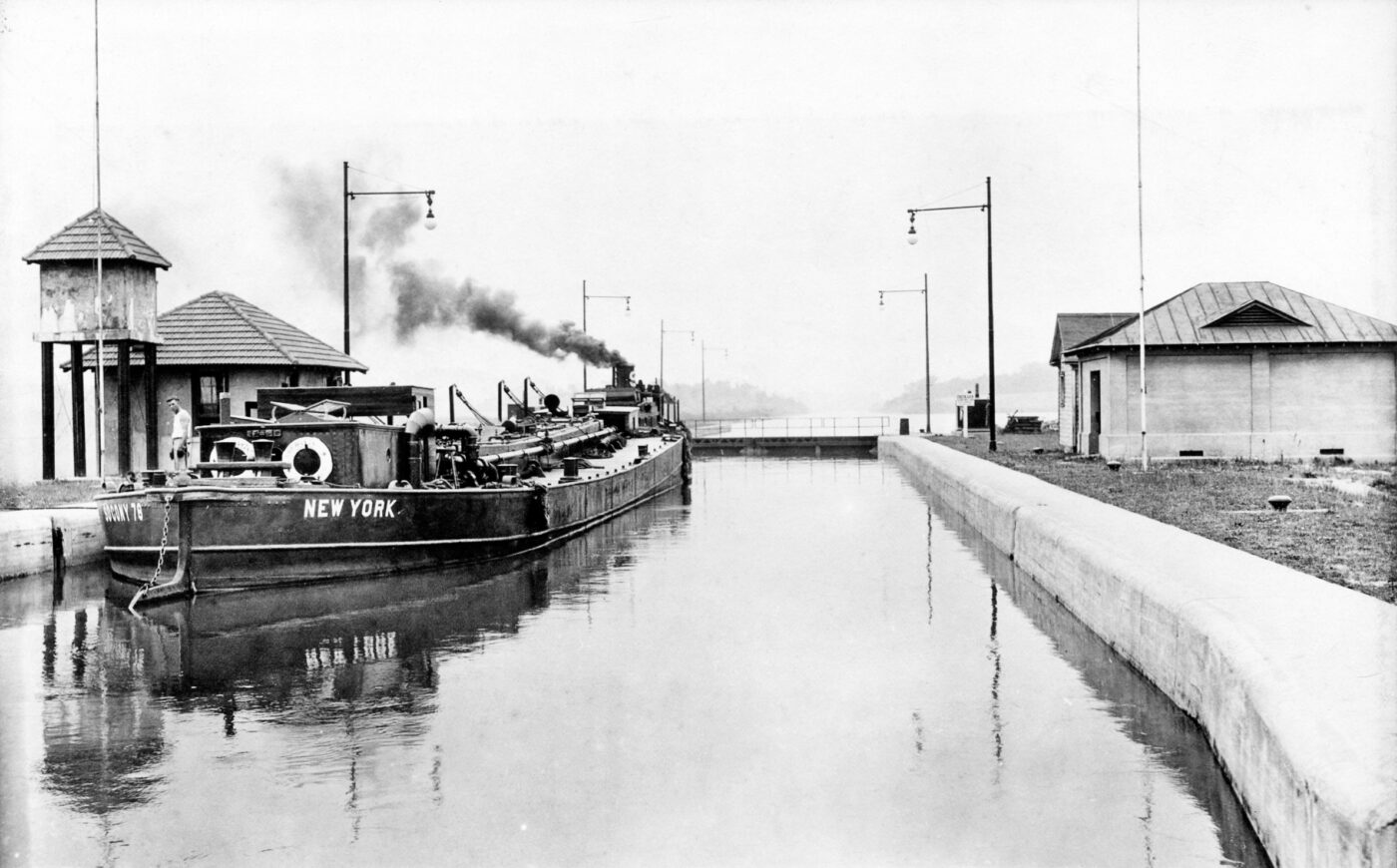

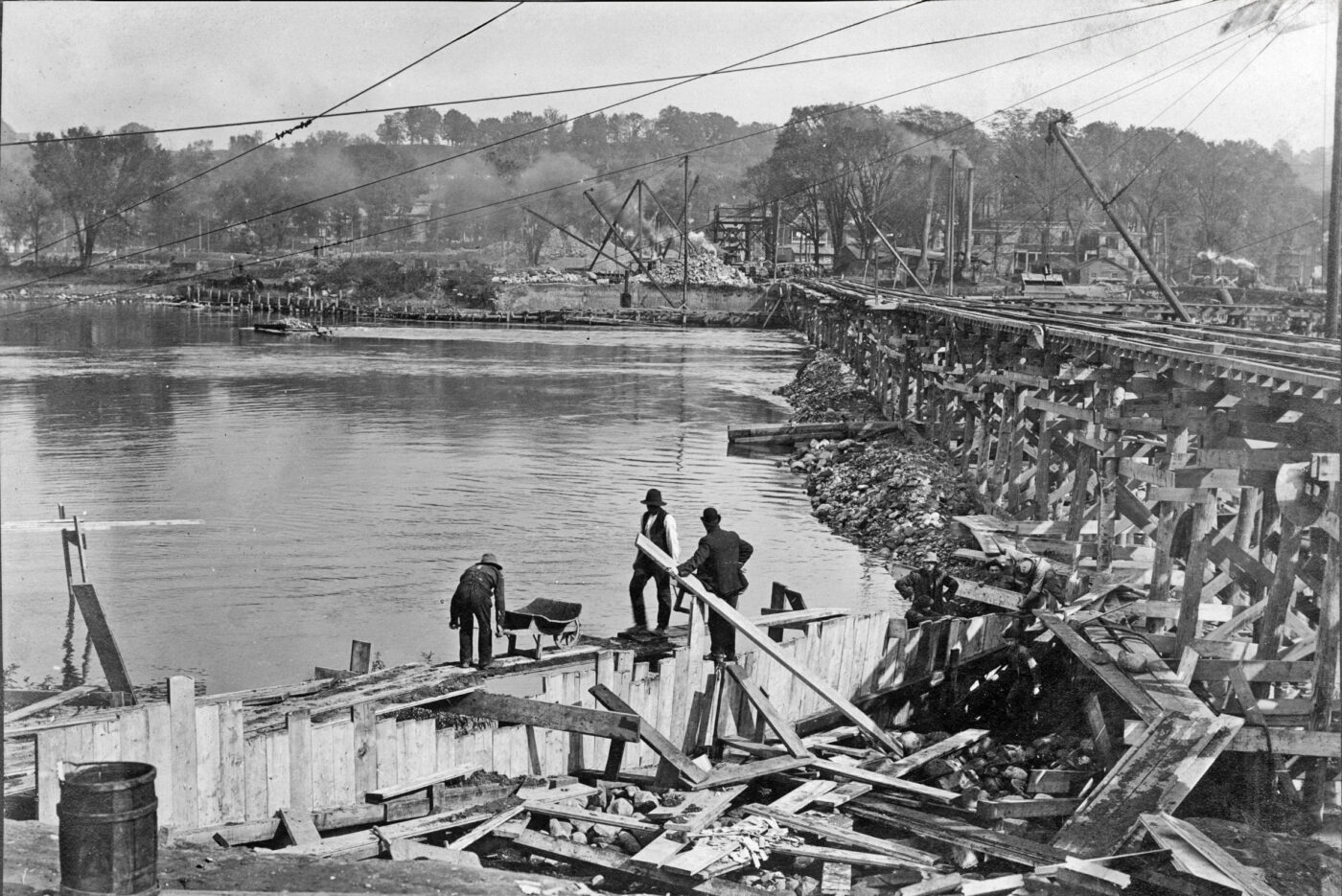

Not long after it was completed, the Erie Canal got crowded. Twice it was expanded to accommodate increasing traffic: enlargements between 1835 and 1862, and its evolution as part of the Barge Canal System completed in 1918. But as railway transport and the St. Lawrence Seaway eventually became more favorable options, commercial traffic on the canal dried up by the 1990s.

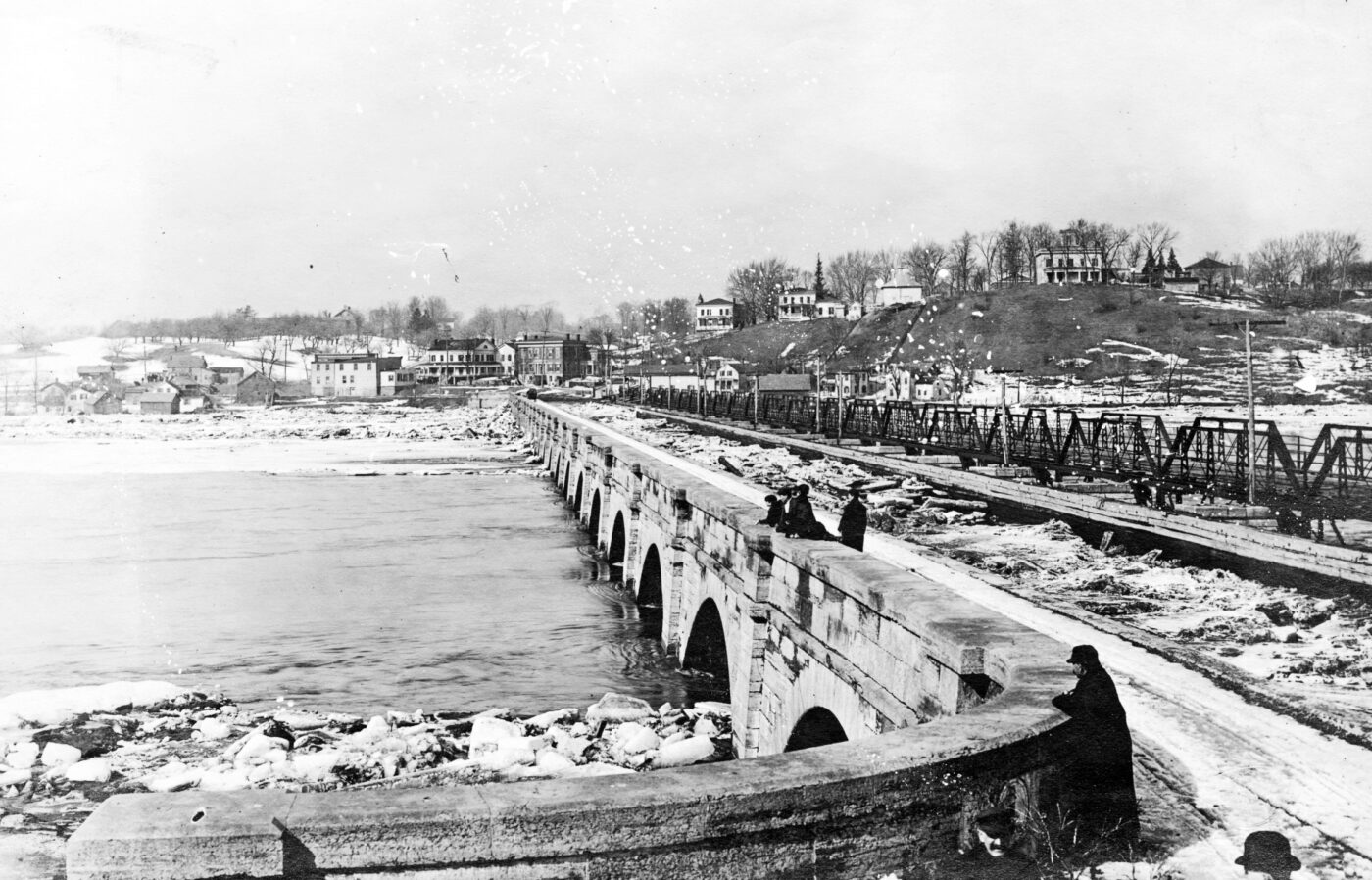

Perhaps the best place to catch a glimpse of the canal’s whole history is at a historic site in Montgomery County, not too far from the Hudson Valley. “Schoharie Crossing State Historic Site features all three major phases of the Erie Canal, from the original ‘Clinton’s Ditch’ of the 1820s to the Enlargement era canal of the 1840s onward, and the site is situated adjacent to the modern and still operating Erie Canal,” says David Brooks, education director and historic site assistant at Schoharie Crossing. The site also features much of the canal’s early engineering, including the remains of an iconic 600-foot aqueduct with 14 arches that once lifted the canal over Schoharie Creek.

As the canal’s path and usage changed over time, smaller towns on its banks had to adapt the most. Montgomery County historian Kelly Yacobucci Farquhar says that when the canal’s route was moved, some of the towns in her county “filled in the old Erie Canal bed and surfaced them to become streets and/or building sites.”

While many businesses and communities that relied on the canal suffered when commercial traffic subsided, Farquhar says some have found ways to keep going. “The community of St. Johnsville utilized the Barge Canal to operate a marina which is still in use today for recreational traffic,” she says. “Other communities are now also working toward that recreational traffic with creation of riverfront parks for events.”

Ecological Challenges Flowing Into the Modern Age

When the Erie Canal was planned, not much thought was given to how opening a portal between two major waterways could impact ecology. “The term ‘invasive species’ probably didn’t exist before 1958. So they wouldn’t have had really a way to think about that sort of thing at that time,” says Simon Litten, retired research scientist in the Bureau of Water Assessment and Management for the New York Department of Environmental Conservation.

But inevitably, aquatic life began to migrate through the canal. A recent example is round gobies—chubby little bottom-dwelling fish hitchhiked in boat ballast water from Europe-Asia to the Great Lakes around 1990. Slowly, they scuttled their way through the Erie Canal and made their first appearance in the Hudson River in 2021. These fish feed on things like mussels and crustaceans with voracious appetites, often outcompeting native fish for food. Similarly, zebra mussels and European water chestnuts have also used the canal — and other means — to spread to new waters.

The round goby is still on the move, says Stuart Findlay, aquatic ecologist emeritus with the Cary Institute. “It’s spread both north and south through the Hudson. It has a salinity barrier that will keep it out of the harbor, but clearly it’s going north up the Hudson,” he says, noting that the round goby has been documented north of Troy so far, and is at risk of moving into the Champlain Canal. He worries that invasive Asian carp species that are in or near the Great Lakes could soon find their way into the Erie Canal, and be even more problematic for the Hudson watershed. “This is a big, fast-swimming fish,” he says. “They can get through the Erie Canal in a few days.”

Imagining a Future for the Erie Canal

These days, recreational boating has replaced barge transport on the Erie Canal. Many cyclists and pedestrians also use the Erie Canalway Trail that runs alongside the whole canal and includes many of its historic sites and remaining locks. In 2019, the Reimagine the Canals Task Force was convened to explore what a useful future could look like for the canal.

The task force explored preventing aquatic invasive species from passing through certain points in the canal by using hydrologic separation — interrupting the canal flow at certain points to lift boats and remove anything that might be tagging along. Findlay sees this as the best solution to the invasive species problem. “Myself, and many other people, feel that the hydrologic separation, the physical block, is really the only way to go,” he says, arguing that it would be the most cost-effective option in the long run. Unfortunately, decision-makers have been slow to act on it, he adds. “Nobody wants to bite the bullet and get going.”

The task force also proposed several other promising ideas for the Erie Canal’s future, including using the canal as a water management tool for expanding irrigation, controlling river flow in ways that enhance recreational fishing, or restoring wetlands.

“The Erie Canal is an important part of New York State’s history,” Findlay says, adding that he hopes ideas like these will be pursued. Taking action, he says, will ensure that the canal is not only critical to New York’s past, but also an important part of the state’s future.