As the first woman state paleontologist in the country, Winifred Goldring changed the way New York thought about its natural history. What did its forests look like hundreds of millions of years ago? How did its plant life form and evolve? These were the big, awe-inspiring questions Goldring grappled with not just for her fellow researchers, but even more so for the general public.

She began as a paleobotanist for the New York State Museum starting in 1926, and then became the first woman to serve as State Paleontologist anywhere in the country in 1939. And she did it decades before her time — when she retired from her position at the state museum in 1954, women in leadership positions in virtually any industry, let alone the sciences, were still practically unheard-of.

Goldring was born in 1888 near Albany to two true plant appreciators. Her father, Frederick Goldring, had come to upstate New York to manage the orchids at the massive Erastus Corning estate, having been trained as an orchid grower in London’s famous Kew Gardens. Her mother, Mary Grey, was the daughter of the estate’s head gardener.

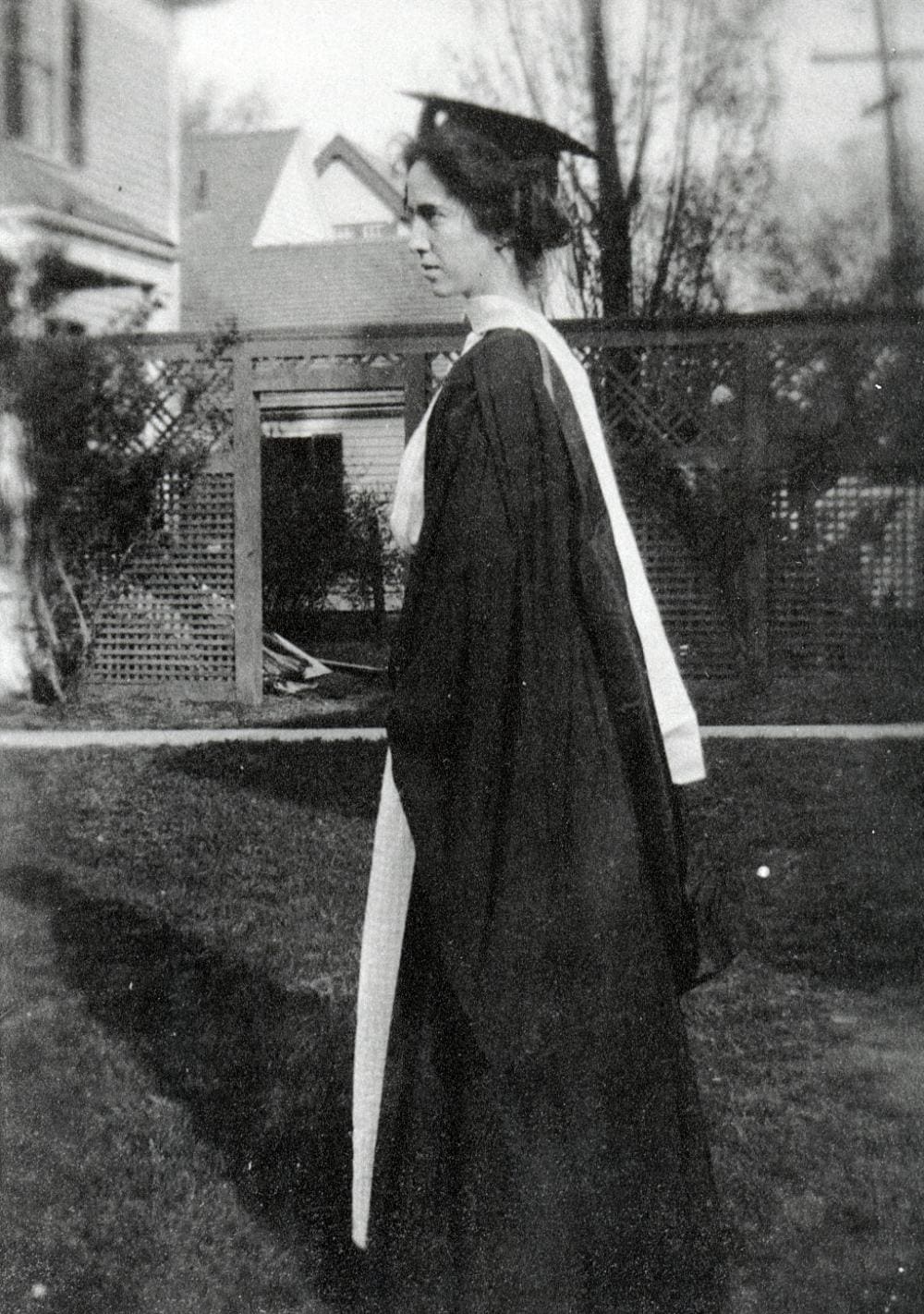

She graduated as valedictorian of her Albany class and went on to Wellesley for college. She also studied at Harvard and Columbia, and finished her graduate work at Johns Hopkins University.

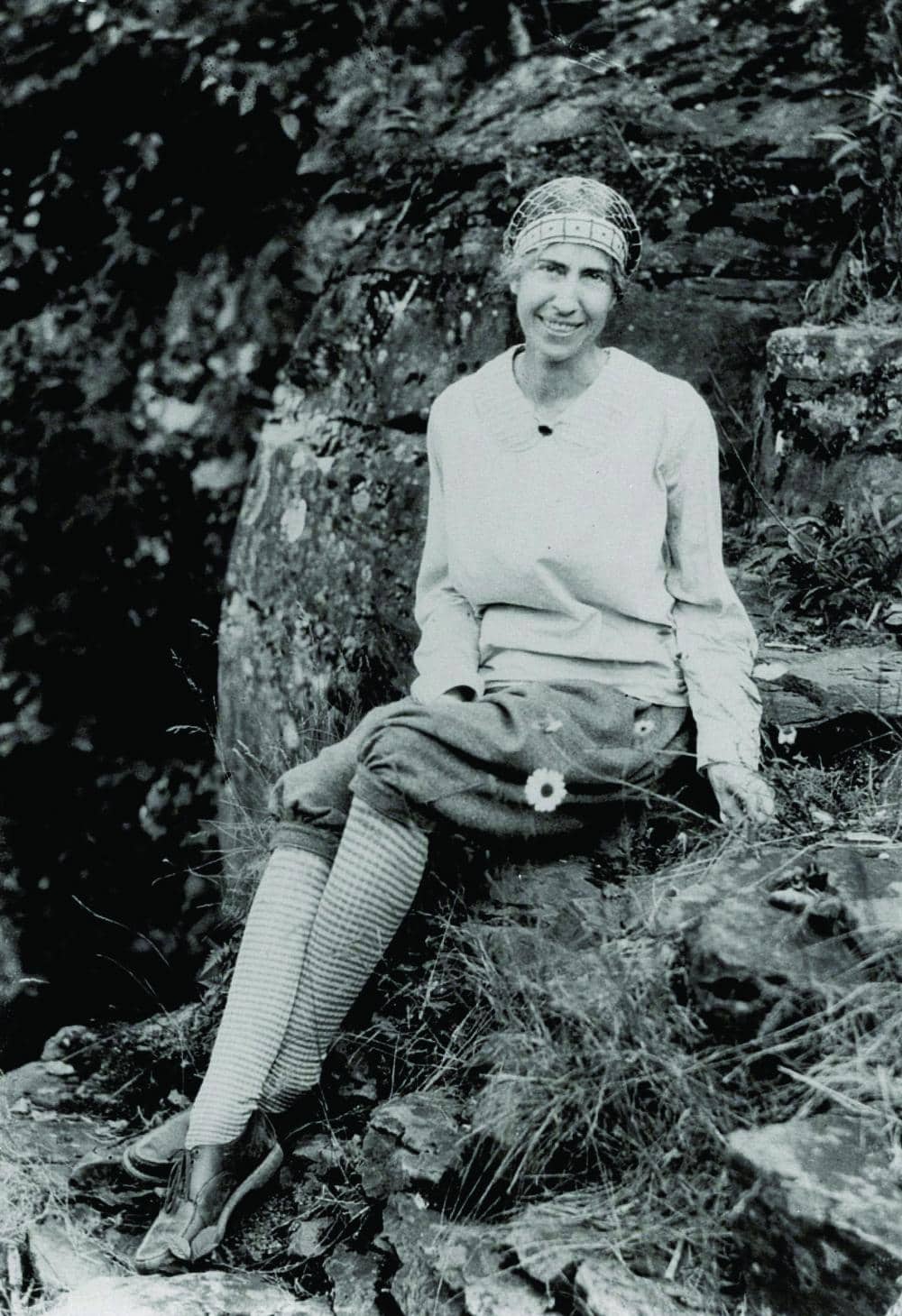

Today scientists tend to be hyper-specialized, but Goldring’s expertise and interests were wide-ranging. She published research on invertebrate paleontology, paleobotany, and even geology, including a full-on geologic map of New York’s Schoharie Valley.

She wrote a two-volume Handbook of Paleontology for Beginners and Amateurs that was designed for the general public to understand the thrillingly ancient science of fossils. The first volume explained exactly how fossils form, how to collect them, and how all the major groups of lifeforms lived.

Perhaps her most famous research came from the 380-million-year-old Gilboa forest, where hundreds of fossilized tree stumps were found in the 1920s. This prime Catskills location became the oldest known Devonian forest in the world at that time.

Goldring then helped create a life-sized museum exhibit of what the forest would have looked like that became nationally known, and stayed on display at the New York State Museum from 1924 to 1976.

She never married, leaving her legacy both with the students and public she inspired, wrote Donald W. Fisher in a tribute to her for the New York Geological Survey. “Possessing a somewhat stern countenance but with a thoughtful and kind heart, she encouraged and gave advice to many budding paleontologists and stratigraphers, as well as to scientists in other fields,” Fisher wrote. Between 1930 and 1950, countless graduate students had her help in devising their research.

“In the United States, it is with great difficulty that a woman accedes to a high position in science,” Fisher added. “Had there been a women’s liberation movement in science in her day, I am positive that Winifred Goldring would have been in the forefront of such activity.”