The opening of Bear Mountain State Park in 1913 flung open the door to a new era of tourism in the Hudson Valley. Within a short time more than 1 million visitors per year were flocking to the mid-Hudson to experience the region’s natural beauty.

The popularity of the automobile had allowed for new travel experiences — but crossing the Hudson River south of Albany still meant a trip by ferry or boat.

In the early 1920s, Hudson River Day Line steamboats and local ferries were filled to capacity with visitors from the New York metropolitan areas. This often led to waits of several hours, sometimes even overnight, at ferry terminals, according to historian Kathryn Burke, director of Historic Bridges of the Hudson Valley.

A Hudson River crossing to transport goods, primarily coal from Pennsylvania destined for New England, had been discussed for decades, and the narrow stretch of river between Bear Mountain and Anthony’s Nose was chosen. The Hudson Highland Suspension Bridge Company incorporated in 1868 with plans ranging from a simple railroad crossing to a two-tier system that would allow for a train crossing on the upper level and a cart and pedestrian crossing on the lower. Land was purchased and surveys completed, but negotiations stalled for decades.

By 1922, the newly formed Bear Mountain Hudson River Bridge Company, directed by E. Roland Harriman, got approval from the New York State Legislature for a bridge. The approval included a provision that the state would obtain ownership of that bridge after 30 years, or sooner if necessary, without incurring any tax burden.

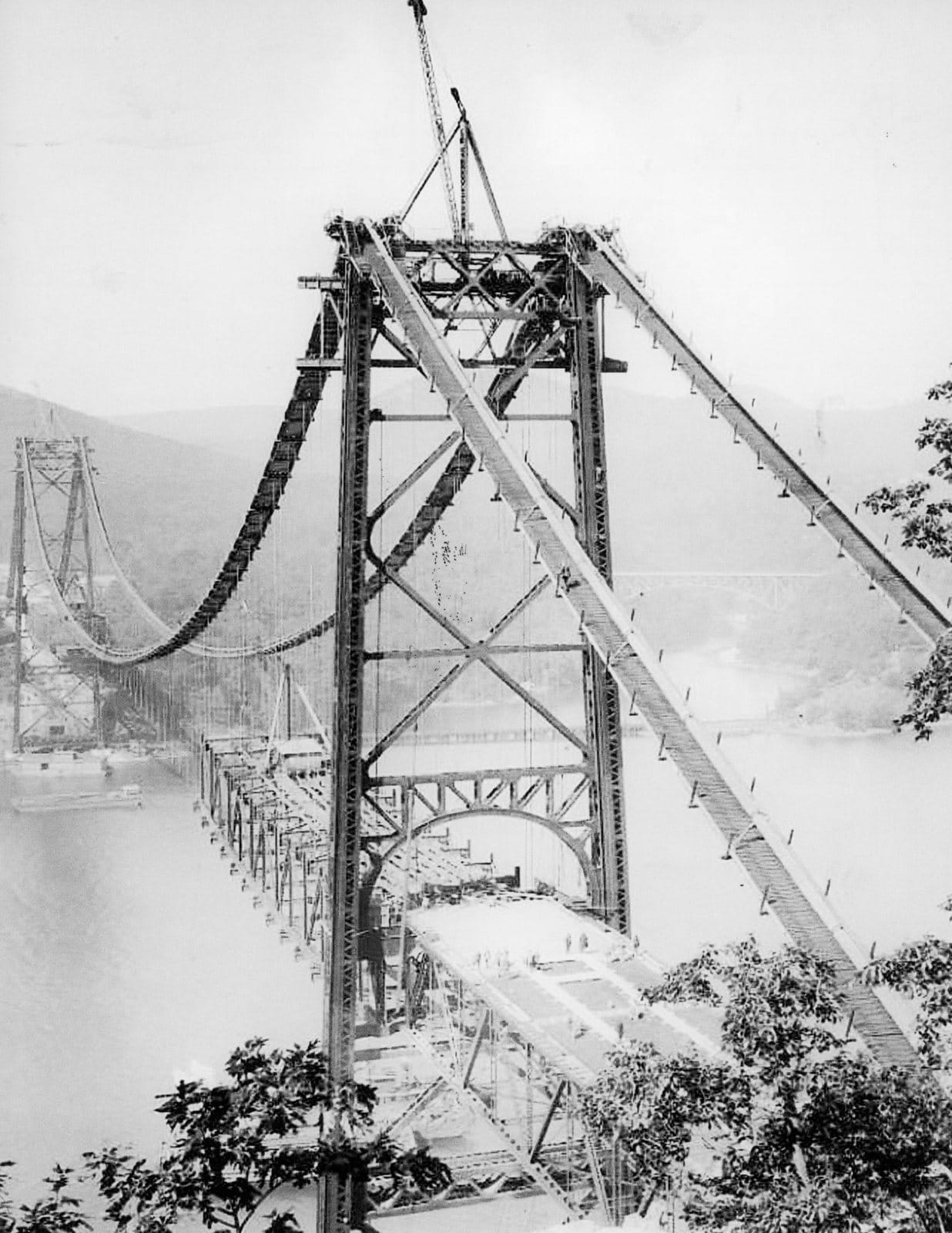

The scenic wonders of the Hudson Highlands were a key consideration in the design of the bridge, as was the need to avoid disrupting river navigation. Plans were made for a suspension bridge anchored directly into the rock on either side of the river. The state required that both the bridge and the highway be finished within three years.

Initial designs called for a western bridge approach running through New York State military reservation property, but the New York National Guard refused, arguing that bridge users might accidentally encounter gunfire. Instead, the approach crossed state-owned land that had once been the site of Revolutionary-era Fort Clinton, “something that would never happen today,” Burke says.

New York City contractors Terry and Tench, Inc., were hired to build both the bridge and the Bear Mountain Bridge Road, a scenic approach on the eastern side of the river (known locally as “The Goat Trail”). Construction began on March 24, 1923, with crews of 250 men working on each side of the river. Just 20 months later, on October 13, 1924, former New York Governor Benjamin B. Odell drove the last rivet into the world’s longest suspension bridge.

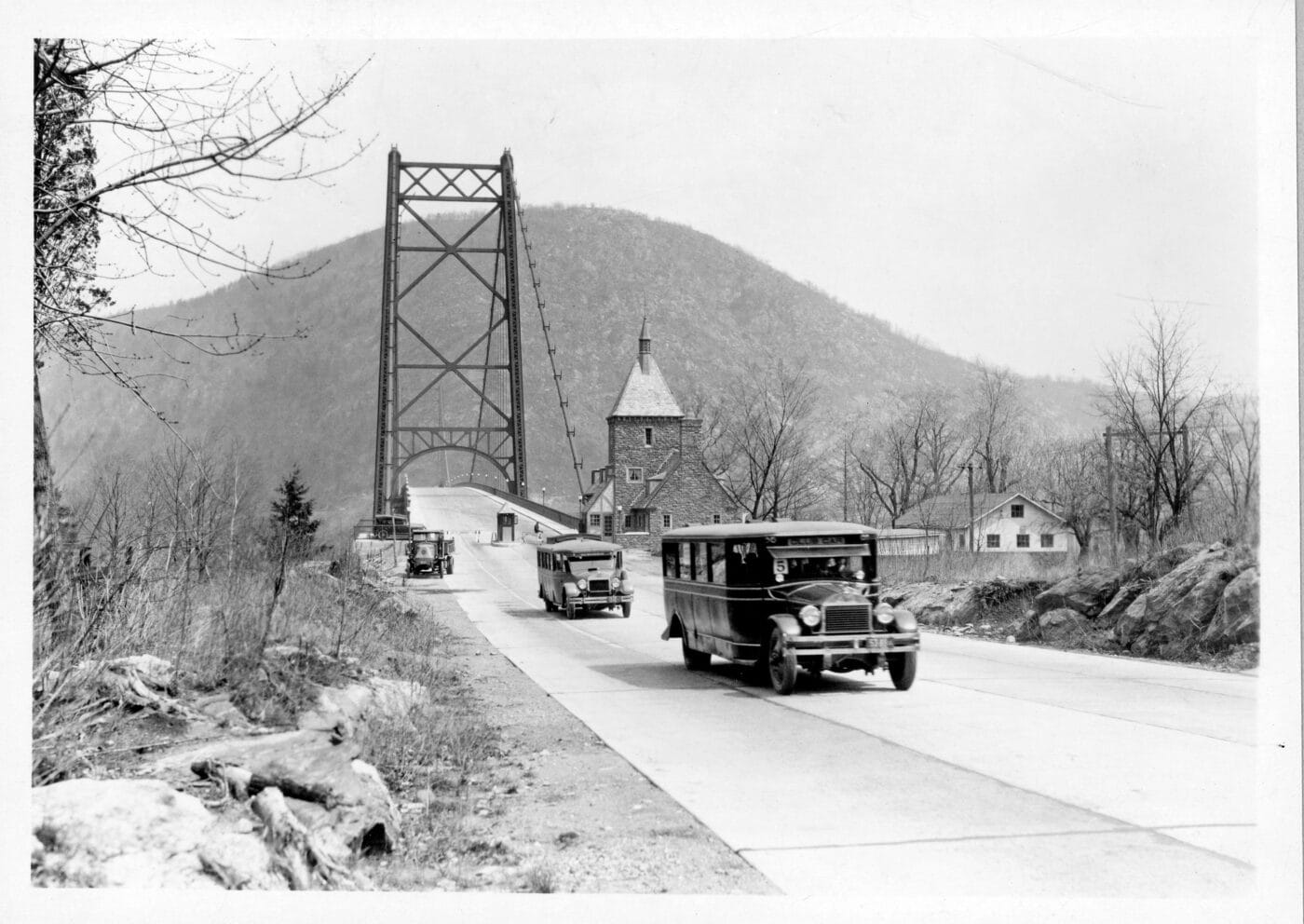

The new Bear Mountain Hudson River Bridge stretched 2,250 feet, with a concrete deck 150 feet above the Hudson. It joined four counties – Orange and Rockland on the west shore and Putnam and Westchester on the east — and opened up a new era of exploration. A dedication ceremony was held on November 26, 1924 and the next day, Thanksgiving Day, more than 5,000 vehicles crossed the new bridge.

The Bear Mountain Bridge Co. heralded the connection between New York City and nature, advertising the ease of travel between urban areas and “the vast outdoor public playground at Bear Mountain (Harriman Park)…one of the most magnificent motor trips in the United States.”

“Prior to 1923, much of the land between here and New York City was still farmland,” former City of Peekskill historian Frank Goderre explains. “Suddenly there was a need for parkways, more roads, local towns saw the biggest population and business boom they ever had. The Bear Mountain Bridge changed everything.”

The new bridge also opened the doors to greater opportunities for outdoor enthusiasts. Just one year prior, a small group of volunteers had broken ground at the base of Bear Mountain, creating the very first section of the Appalachian National Scenic Trail. When the trail was completed in 1925, the bridge became an essential section of the nearly 2,200 mile-long footpath.

Ease of crossing came with a price however, as tolls were set at 80 cents for a car and driver each way, with an additional 15-cent charge per passenger. Pedestrians were charged 10 cents — unless they walked a bicycle across, in which case they were charged 20 cents — while horse-drawn wagons paid a toll of up to 75 cents. Because so much cash was collected each day, Goderre says, it was necessary for toll collectors to carry firearms.

The New York State Bridge Authority took over management of the span on Sept. 25, 1940. Tolls were reduced to 50 cents per vehicle each way, then 25 cents and eventually collected only on the eastbound side.

The Bear Mountain Bridge (along with the eastern Tollhouse) was placed on the National Register of Historic Places in 1982 and named a Metropolitan Area Historic Civil Engineering Landmark in 1986 by the American Society of Civil Engineers. In 2018, in an act of the New York State Legislature, it was given the ceremonial designation “Purple Heart Veterans Memorial Bear Mountain Bridge.” Though it no longer holds the distinction of being the longest suspension bridge and other vehicle crossings have long since been constructed over the Hudson, a century later the Bear Mountain Bridge remains an integral gateway to exploration in the Hudson Valley.