Brickmaking along the Hudson River dates back to the early 1600s, but New York City’s growing building-material needs during the 19th century, coupled with the ease of transporting materials on the Hudson, spawned a booming industry. By the early 1900s, more than 130 brickyards were active along the river. One of most prolific was the Jova Brickyard in the Orange County hamlet of Roseton, founded by a Cuban immigrant who turned to brickmaking when his original business plans fell through.

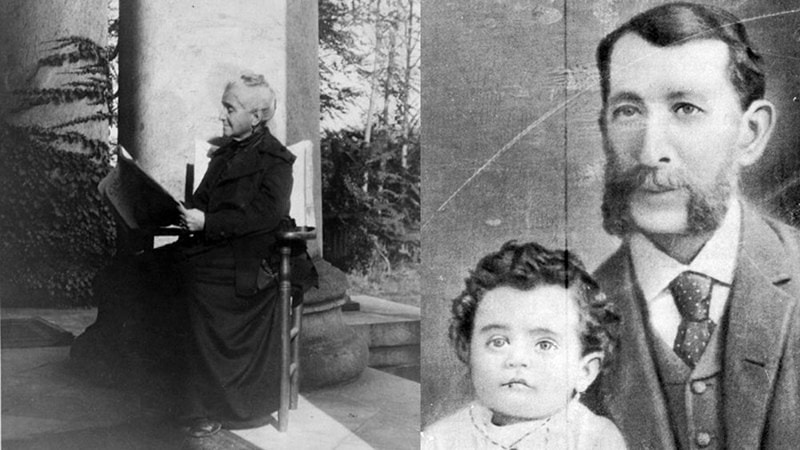

Juan Jacinto Jova was born in 1832 in Villa Clara, Cuba. He emigrated to New York City as a young man and graduated from Columbia University with a degree in civil engineering. Jova first established himself as a sugar broker in the city, but seeing his business decline after the Civil War, he turned to the Hudson Valley in pursuit of other business ventures. He saw clear possibility upon learning about the rich clay deposits and the flourishing brick trade in the area.

In 1874, Jova purchased Danskammer, a Greek revival home and property along the Hudson River about four miles north of Newburgh, where he eventually lived with his wife Marie and their growing family.

He continued to work as a sugar broker in New York City for nearly a decade, devoting any free time he had to learning the brick trade. Jova’s neighbor, John B. Rose, had already established a thriving manufacturing center as well as a small company town.

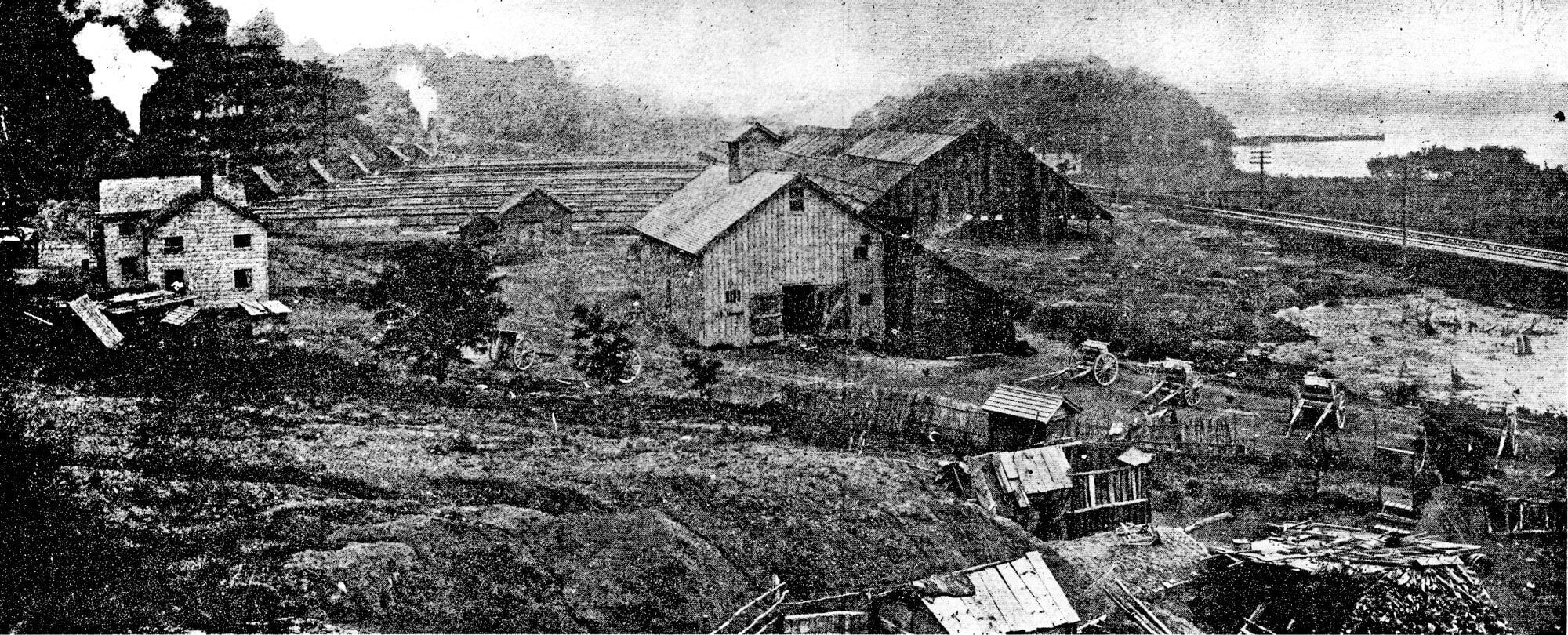

Roseton, as it was called, was rapidly developing so that workers could live, worship, and shop within walking distance from the Rose brick plant, a model that Jova found appealing. The Danskammer property contained some of the deepest clay deposits along the Hudson, at nearly 240 feet thick. Jova invested heavily in machinery and studied the methods used at the Haverstraw yards in Rockland County as well as at the neighboring Rose and Arrow plants in Roseton, and in 1884 began operating as Jova Brick Works.

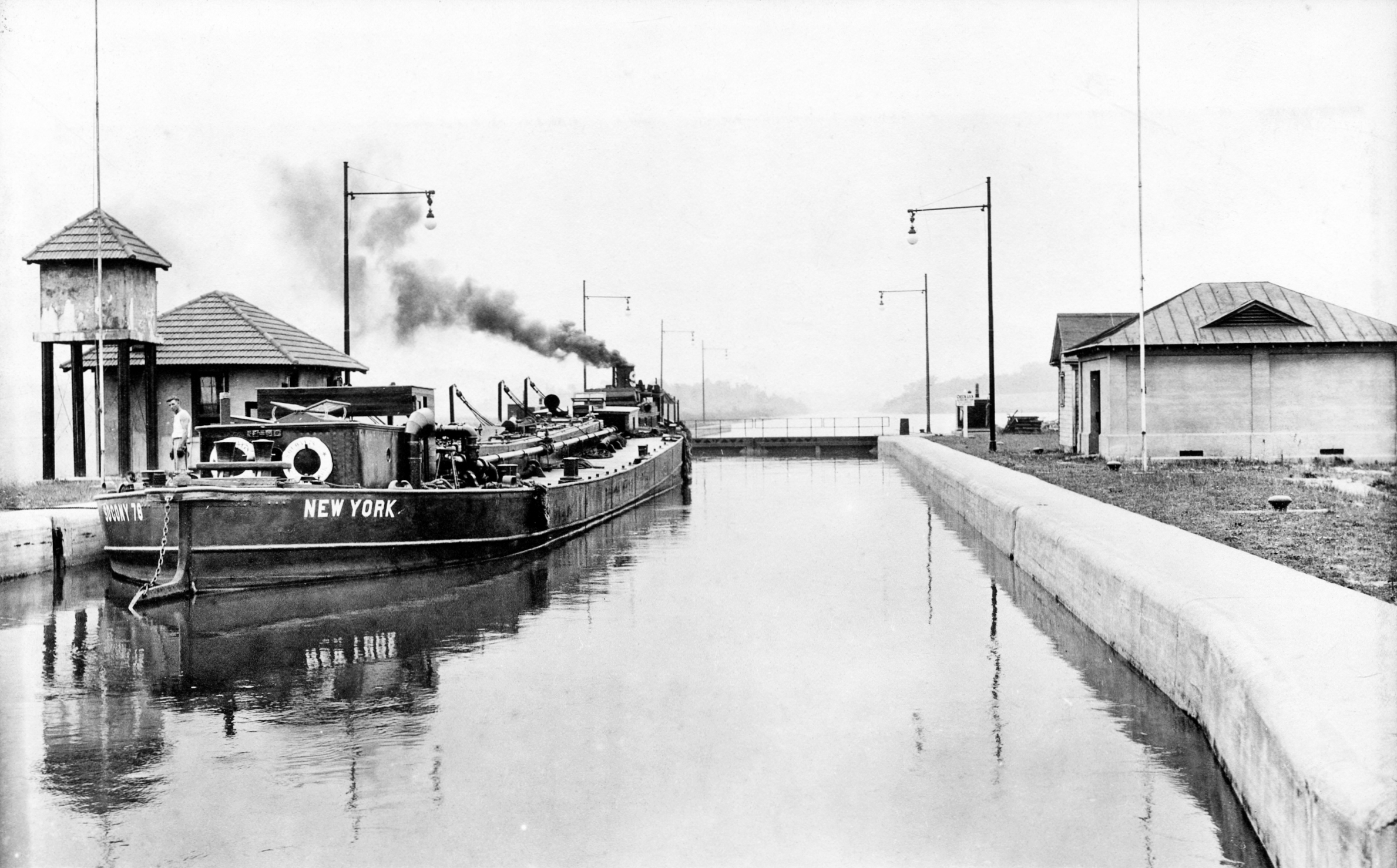

He hired highly-trained leaders to serve as foremen and superintendents, and commissioned sheds, docks, and three barges to facilitate export of his bricks to the city. Jova bricks, with their distinctive “JJJ” imprint, quickly became known for their high quality and commanded top prices. Jova bricks were soon found in some of New York City’s most iconic structures, including the Waldorf Astoria, the Harvard Club, the Brooklyn Navy Yard, and eventually the New York Public Library’s main branch on East 42nd Street.

Jova followed John B. Rose’s lead in building company housing and stores, and helped his employees to find other work along the river in the winter months when brickmaking slowed. In 1891, he enlisted the help of his wealthy contacts to raise money for a church in Roseton for his largely Catholic workforce. Our Lady of Mercy was built on his property (of Jova bricks, naturally) and was presented as a gift to the community and the Archdiocese of New York.

Juan Jacinto Jova died in 1893 at the age of 61, and his sons Henry, Jules, Edouard, John, and Joseph took over the Jova Brickyard. Jova’s sons shared his head for business and invested in the latest technologies, keeping the company in business long after many other Hudson Valley brickyards. By the early 1900s, the Roseton plant employed upwards of 350 workers (the majority of them Irish, Hungarian, and Polish immigrants, as well as Southern Black workers seeking higher wages) and was producing nearly 40 million bricks each year. Operations at the Roseton brickyards were visible to passengers on Hudson River trains and boats, and the Jova yard stood out with an immense sign reading “Build With Brick” in 10-foot-high letters on the kiln sheds.

By the early 1920s, the “Jova Boys,” as they were known, shifted operations from 14 manual soft mud brick machines to automated soft mud machines, the first to be used in the Hudson Valley. Other improvements included new systems for loading and unloading barges, innovative drying methods, and experimentation with custom hues. While Jova’s sons carried on the business, his widow Marie continued his charitable works, donating Jova bricks for use in building local schools and churches.

The brickmaking era slowed during the 1930s and 1940s, and most Hudson Valley brick companies closed. New York City skyscrapers being constructed with steel and cement instead of brick, new environmental regulations, and cheaper labor costs in Southern states all played pivotal roles in ending the local brick industry. The Jova family continued to adapt to the changes, and Jova remained one of the last active companies, even expanding with the purchase of the century-old Hutton brickmaking plant in East Kingston in 1965 (“JMC” or Jova Manufacturing Company bricks are indicative of this timeframe). Their reign came to an end shortly after, however, with the Roseton plant closing in 1968 and the East Kingston property sold in 1970.

Today the brickyards along the Hudson River are long gone, as are many of the communities that once thrived in their wake. The hamlet of Roseton has all but disappeared, and Our Lady of Mercy, the church commissioned by Juan Jacinto Jova, remains the only significant structure from Roseton’s brickmaking era. The Jova Brick Works site, along with those of the other Roseton companies, are now home to looming power plants, and piles of brick pieces are the only clues to the earlier businesses on those sites.

Jova bricks, however, have stood the test of time and can still be found in the buildings and sidewalks of New York City, as well as countless structures throughout the Hudson Valley.