On a rainy weekend in May, a few dozen hardy and curious hikers gathered near Route 9W in Bear Mountain State Park. There they met Donald “Doc” Bayne, an environmental educator and historian at Sterling Forest State Park. Bayne was about to lead them on a spot of land in the Hudson River that has intrigued him since he was a teenager. “I always wondered, What is Iona Island?” says Bayne. “I mean, what is it. I drove out there onto the causeway when I was 17 — and got thrown out.”

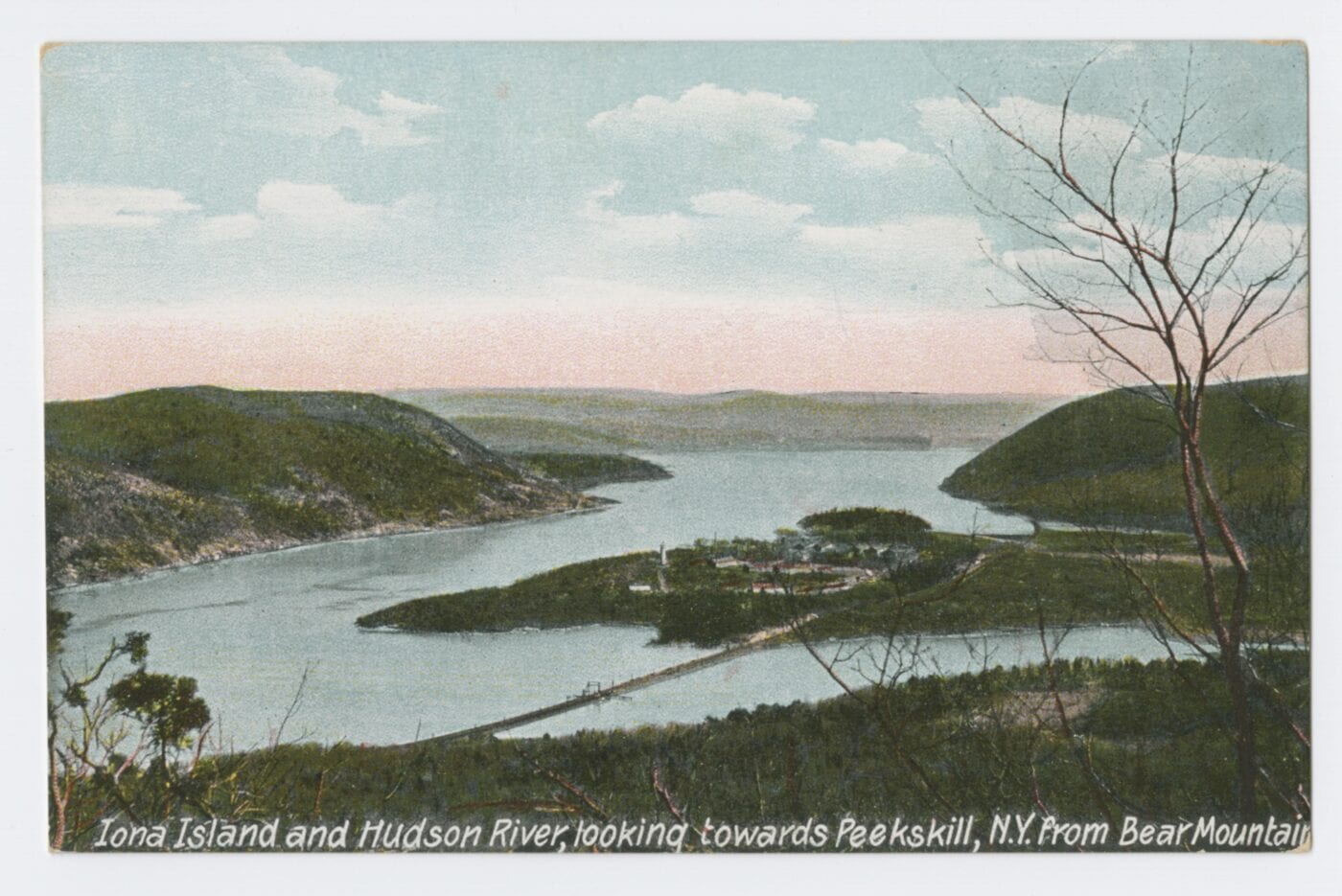

Bayne surely isn’t the only local to wonder about Iona, which when the tide is in, is actually a small archipelago of three islands near Doodletown. But he now knows as much as anyone about its colorful history and leads occasional hikes for like-minded naturalists through the otherwise closed-to-the-public preserve.

That history begins at least 3,500 years ago, when Indigenous peoples spent the summers here fishing. “There were seven-pound oysters back then,” Bayne says. Native rock shelters still dot what came to be called Rock Land, which joined Salisbury and Round Islands, tidal marshes, and mud flats to make up the bedrock spit of land.

On Aug. 14, 1683, members of the Van Cortlandt family “purchased” the land from Indigenous people. Dutch ancestors lived there for nearly 200 years, during which time Salisbury Island was also known as Weygant’s Island (for a local family named Weygant or Weiant). In 1849, a man named John Beveridge bought it for his son-in-law, Dr. E.W. Grant. “When he got the land, he told people, “I own an island,” Bayne says. “That’s how it got the name.”

“When he got the land, he told people, “I own an island. That’s how it got the name.”

—Historian Donald Bayne, on the origins of the island’s name

Grant used the land to grow a type of grape he called Iona grapes. “Turns out they weren’t very good grapes,” Bayne says. Grant also planted fruit trees and supplied the Union Army with produce during the Civil War. That didn’t work out so well either, and in 1868 his creditors foreclosed on him. The next year the island was sold to a group of investors and turned into a summer resort.

Grant’s mansion became a hotel, and the investors gradually added a carousel, dance floor, and pavilion. Steamships — up to 25 a day, carrying as many as 2,500 people — came up from New York and New Jersey and deposited weekenders. And in 1882, the West Shore railroad opened, bringing even more visitors. “It was said that during its height you couldn’t walk 10 feet without stepping on a blanket,” Bayne says.

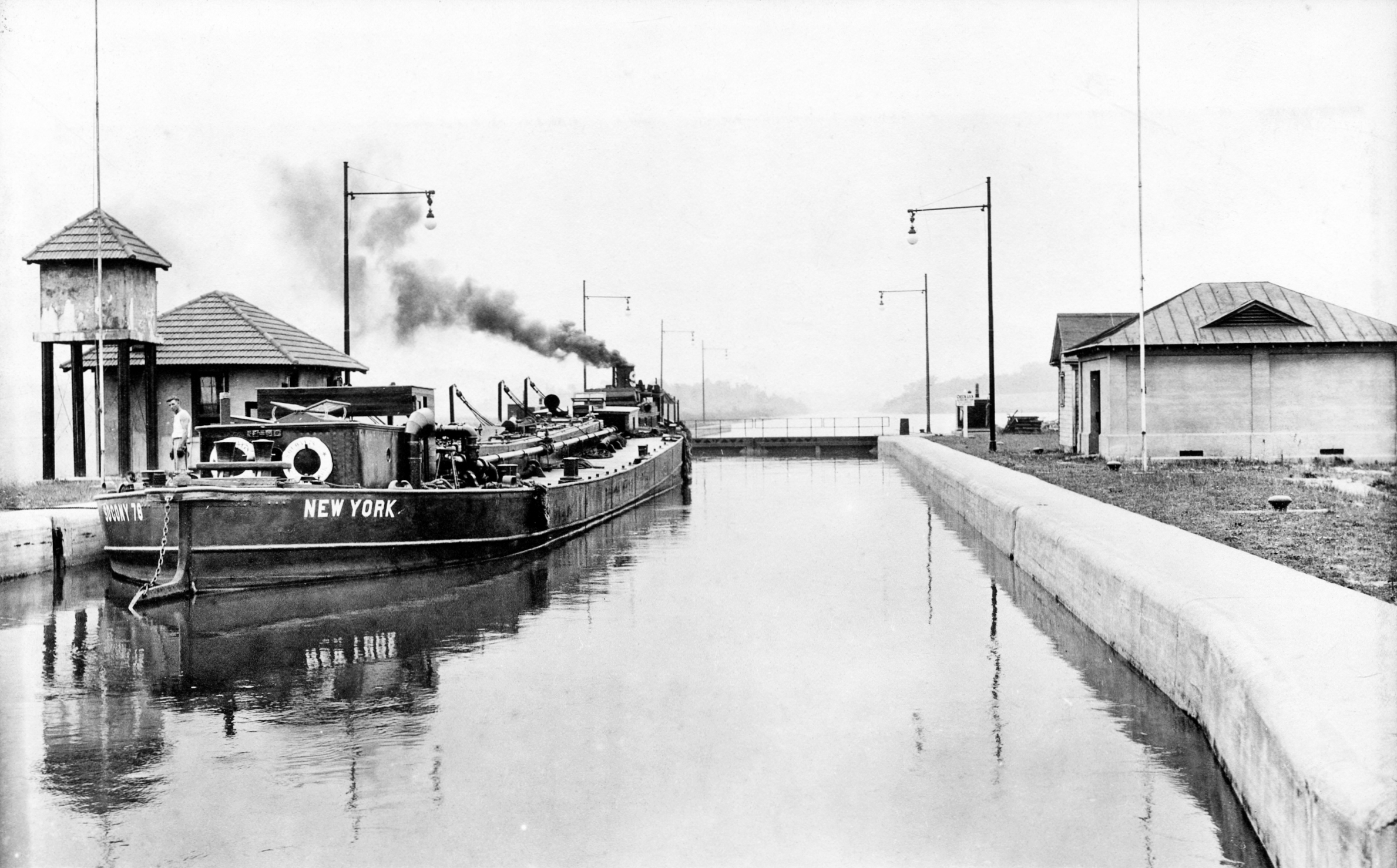

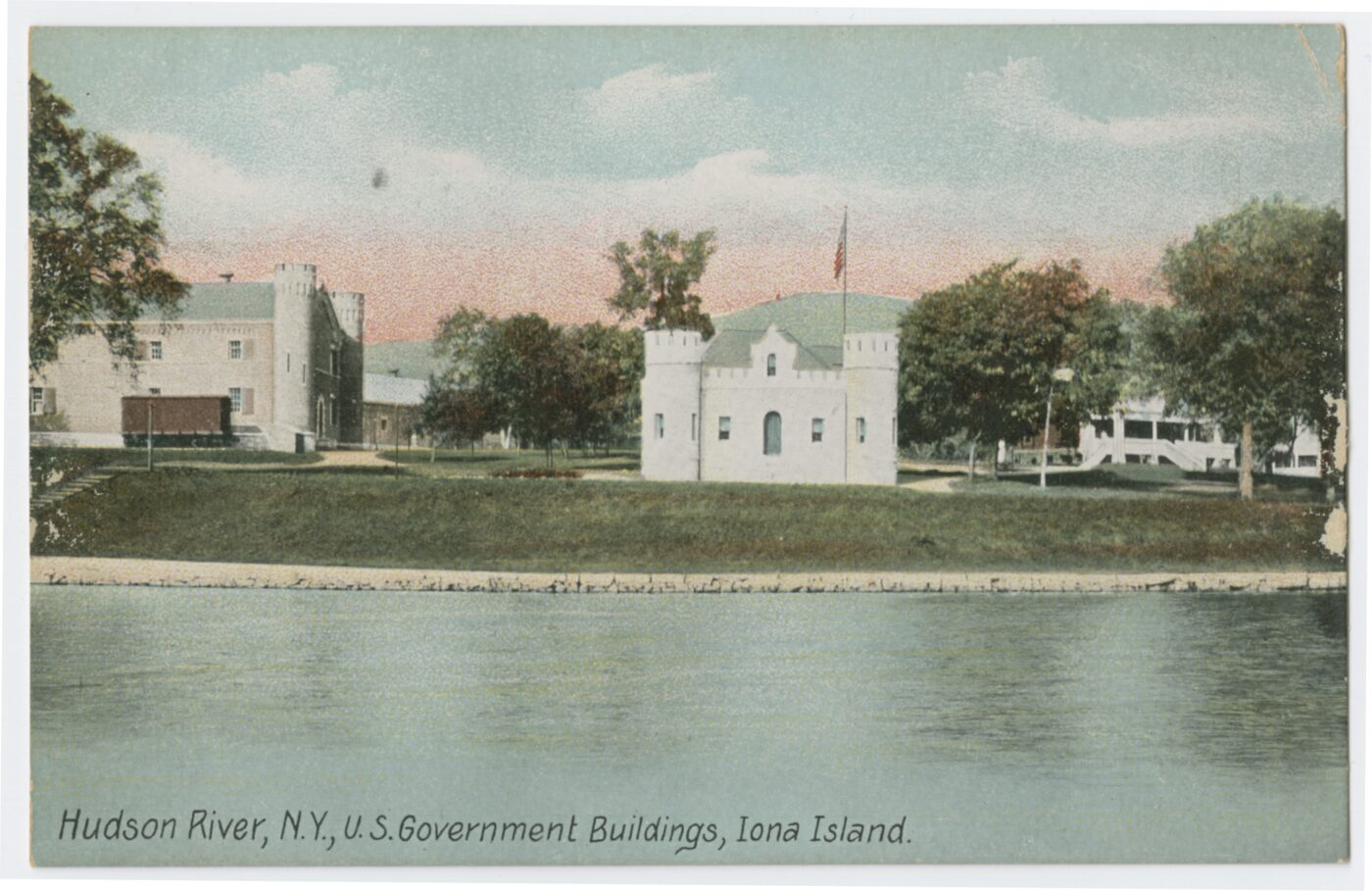

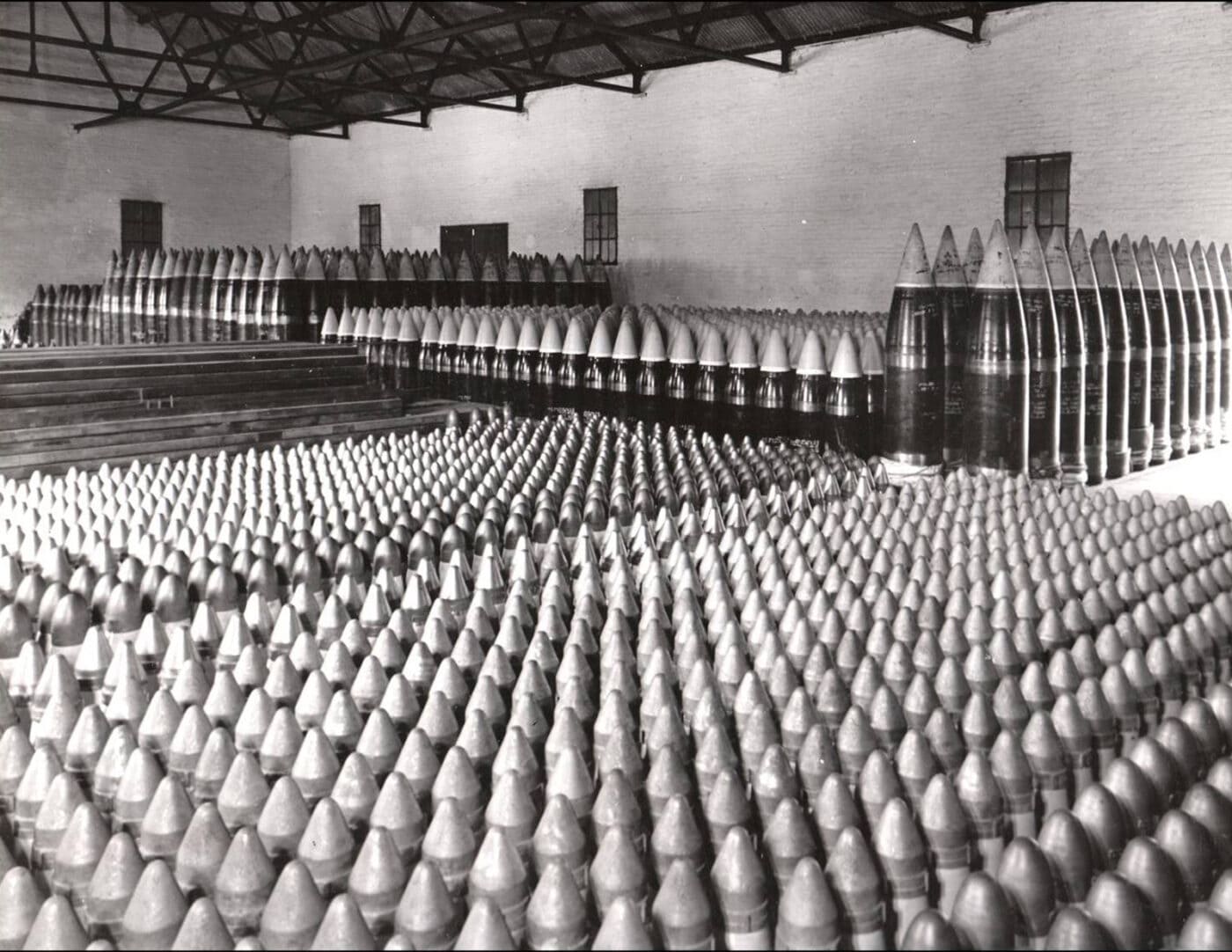

The fun ended in 1899 when the owners sold out to the U.S. Navy, which needed an ammunitions depot. “It supplied most of the munitions for both World War I and II,” Bayne says. After the wars, the navy built other depots, and Iona became a storage facility for the Defense Department in the 1950s.

The fun almost returned in the 1960s, when the state bought it as part of the Palisades Interstate Park Commission. Governor Nelson Rockefeller envisioned new boat docks, man-made beaches, and swimming areas. The old buildings were torn down and the island cleaned up. “Then Rocky left office and there was no money,” Bayne says.

To naturalists like Bayne, that may have been the best thing to happen to the island and its wetlands since Indigenous people sold it to the patroons. In 1974, Pete Seeger held a concert for Clearwater on the island, and that same year it became a registered National Natural Landmark.

It was closed to the public in the 1980s and today looks much like it did before the Europeans arrived. It has become a prime spot for bald eagles to nest, and dozens of other avian species draw birders and their binoculars. Native animals and plants have returned as well. “It’s being reborn, going back to what it was,” Bayne says.