Along with brick-making and ice harvesting, the manufacturing of natural cement earned the region national renown in the 19th century. It also helped fuel the growth of the Ulster County community, Rosendale, that was blessed with an abundance of the natural resource essential to its production.

The area’s cement works started to wane a good century ago, and the very last one shut down 50 years back. Yet Rosendale continues to thrive — and its old mines and railroad infrastructure still inspire wonder. Here are some impressive facts about this historic industry.

It owed its existence to marine invertebrates that lived on the sea floor below the equator some 400 million years ago. After they died, geological upheavals caused them to harden into the mineral calcite, a prime ingredient of limestone, and continental shifts brought the rock north. A major deposit of limestone particularly rich in calcite wound up occupying a narrow swath of land — just 18 miles long and a mile wide — in Ulster County.

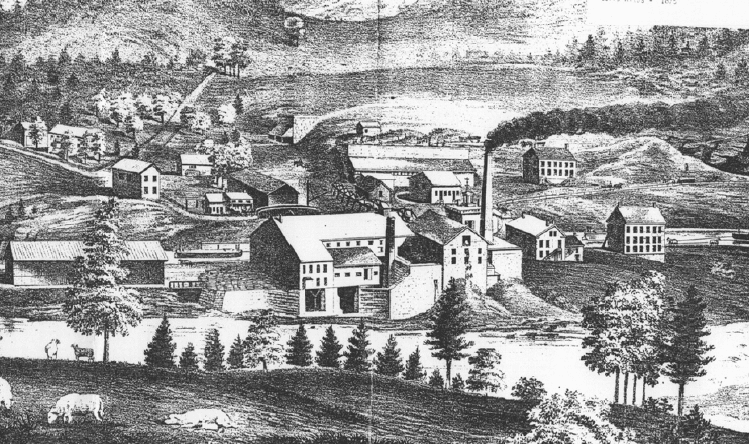

The industry began by happenstance. In 1825, workers constructing locks on the Delaware and Hudson Canal in Ulster County recognized that the limestone along the route contained just the right amount of calcite to produce a fast-drying, strong, and waterproof cement. The first local operation to manufacture it began in 1830. The canal went on to play an important role in the industry’s future growth, hastening supplies of raw materials and transportation of the finished product to market.

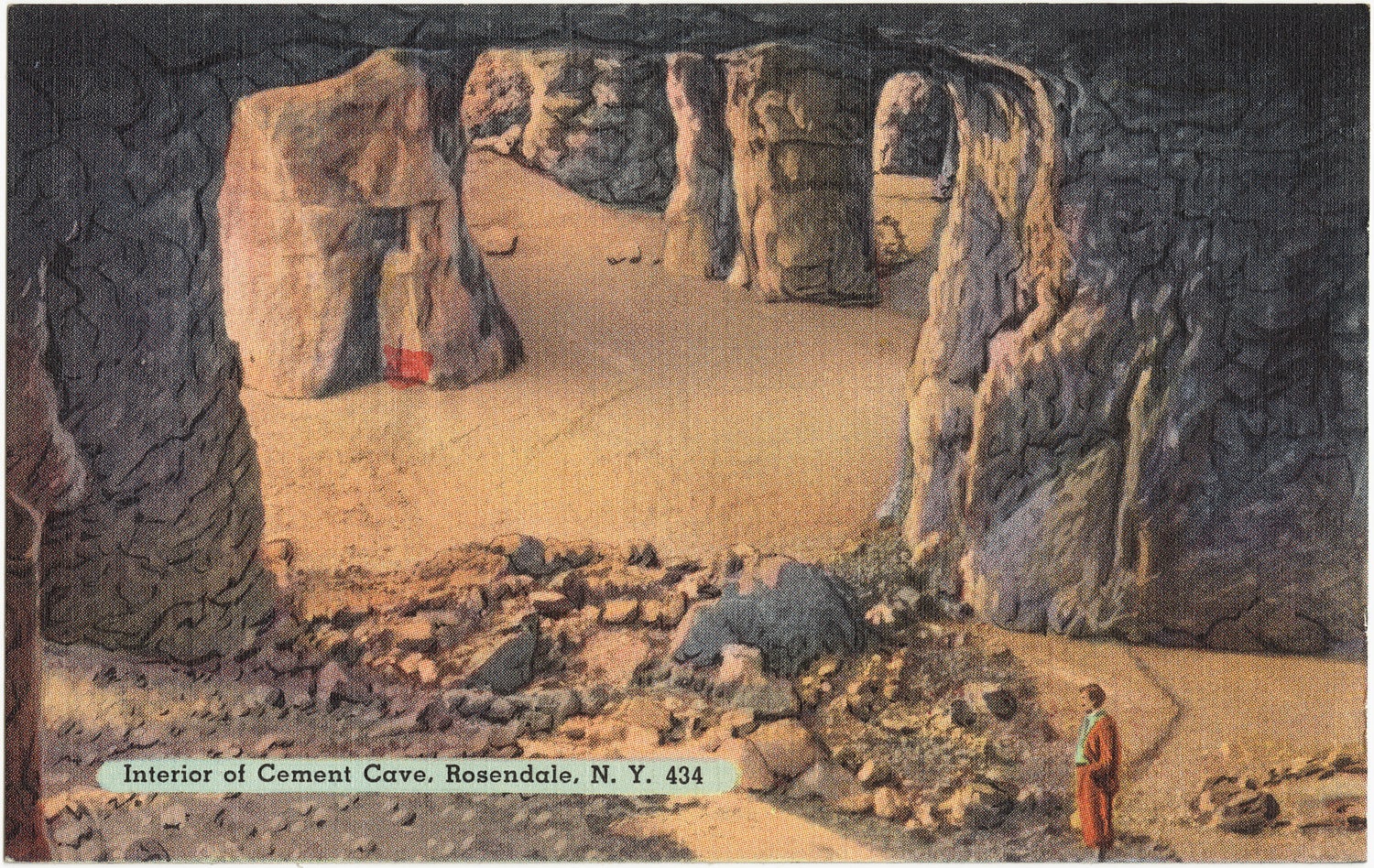

More than 100 cement mines honeycombed the area. Relying solely on hand tools until the invention of hydraulic drills and electricity, miners crafted these subterranean chambers, some cavernous in size, that kept growing as more rock was hauled away. To keep the mines structurally sound and prevent cave-ins, stone “pillars” were left at intervals. This process, known as “room and pillar mining” was not terribly efficient — it left behind a lot of usable limestone — but it did increase worker safety in mines that could extend for miles below ground.

A town grew up around it. Rosendale was established in 1844 to incorporate the hamlets that sprung up near the mushrooming factories created to mine the rock and produce the cement. Their output, which eventually was marketed as “Rosendale cement,” was generally considered North America’s highest-quality natural cement.

Rosendale cement once led the way. At the height of operations in the late 19th century, the town’s dozen-plus cement factories shipped 10 million barrels of their product to market annually — more than half of the country’s total output. It was used to construct the base of the Statue of Liberty, the Brooklyn Bridge, the west wing of the U.S. Capitol, Grand Central Terminal, and other enduring landmarks.

Kilns turned the rock into cement. Mined rock was hauled by horse- or oxen-drawn carts, or sometimes via trams running on tracks. The rock was taken to the tops of large stone kilns, then dumped into the heat along with fuel. (Initially, that fuel was wood, which decimated surrounding forests; later, it was coal). After being “cooked” at a temperature over 1,600 degrees F, the limestone was powdered by running it through grinders and the resulting cement packaged in barrels. Kilns remained in operation 24 hours a day from March through December.

Laborers were primarily foreign-born — and young. Some 90% of the industry’s 5,000-person workforce were immigrants, mainly from Ireland, and teens and even children filled the 10-hour shifts. “Without their contribution, their families wouldn’t survive,” says Gilberto Villahermosa, author of the book Rosendale. Orphan children were pressed into doing the most perilous work — crawling into the deepest and narrowest crannies of the mines to extract rock.

Speed doomed the industry. By 1900, Portland cement started taking precedence over natural cement. Produced by heating limestone with clay, shale, iron ore, and other additives, Portland cement hardens more quickly, allowing builders to work faster — critical during the 20th-century boom in constructing skyscrapers, dams, highways, and airport runways. This put the Rosendale cement industry at a distinct disadvantage and led to the factories’ gradual closing. The last one, the Century Cement Manufacturing Company, hung on until 1970. Today, Freedom Cement, based in Massachusetts, occasionally quarries rock from a Rosendale mine to manufacture small batches of cement used to restore historic structures such as the High Bridge in the Bronx.

Old Rosendale cement mines have supported some interesting new ventures. The innovative adaptive reuses have included cultivating mushrooms, breeding trout, and storing records. A Brooklyn-based distillery “harvests” limestone-enriched water from one mine to produce whiskey. The Widow Jane Mine, the only one open to the public, hosts tours as well as provides a venue for concerts, poetry readings, and other events.

There are many opportunities to explore the industry’s remnants. Unlike the ice harvesting and brick-making industries, substantial artifacts remain from the glory days of manufacturing Rosendale cement. Take a drive along the town’s Hickory Bush Road to see more kilns, and don’t miss a visit to the Century House Historical Society. In addition to the Widow Jane Mine, it features several historic kilns as well as a small but excellent museum about the industry.

Visitors can actively immerse themselves in history by taking in the scenery, too. The parking lot for the Wallkill Valley Rail Trail on Binnewater Road in Rosendale contains an impressive phalanx of kilns. Walk, run, or bike northward on the trail itself for several miles to pass an amazing array of mines, kilns, and ruins of ancillary structures.

Reed Sparling is a Scenic Hudson historian and former staff writer for the organization. He is also a former editor of Hudson Valley Magazine, as well as a writer for Reader’s Digest. He continues to co-edit the Hudson River Valley Review, a scholarly journal published by the Hudson River Valley Institute at Marist College.