Late in summer 2018, a Swedish teen plopped down on a sidewalk by the seat of her nation’s government, bearing a handwritten sign that read “School Strike for Climate.”

Greta Thunberg’s message was straightforward and shattering: What’s the point of attending school if schools are ignoring the most substantial crisis facing the planet? In Dutchess County, her message — echoed in the strident voices of the international youth climate movement it spawned — is being heard.

Inspired by the passion and commitment displayed by students and young climate activists, leaders at the Dutchess County Board of Cooperative Educational Services and its member districts are beginning to integrate sustainability and climate education into curricula, student empowerment activities, community engagement and the built environment. The effort is emerging through the Board of Cooperative Educational Services’ (BOCES) newly formed Center for Sustainability and Climate Education, which launched in October 2020.

“This is what schools do,” says BOCES Deputy Superintendent Cora Stempel. “It’s bigger than science class or social studies class. It’s helping these students become the change agents they are so capable of being.”

School districts that join the center can take advantage of services provided by BOCES and the center’s organizational partners: the Omega Institute, the Mid-Hudson Teachers’ Center, the Ashokan Center and the Cloud Institute for Sustainability Education.

Beginning with the 2021-22 academic year, membership will cost $5,000 annually, a portion of which is reimbursable from the state Education Department. Services are either free or offered at reduced costs when compared to hiring outside consultants, Stempel says. They can include support for curriculum design, green building assessments, student empowerment activities or other services.

This spring, BOCES has offered a number of free online events for students and teachers, including a student empowerment panel, a mini curriculum design studio and a daylong Spring Summit.

Though Dutchess BOCES serves 13 school districts in the county that represent approximately 39,000 students, administrators say the center’s services are available to any district. And as the center grows, there is the potential to work with additional organizational partners.

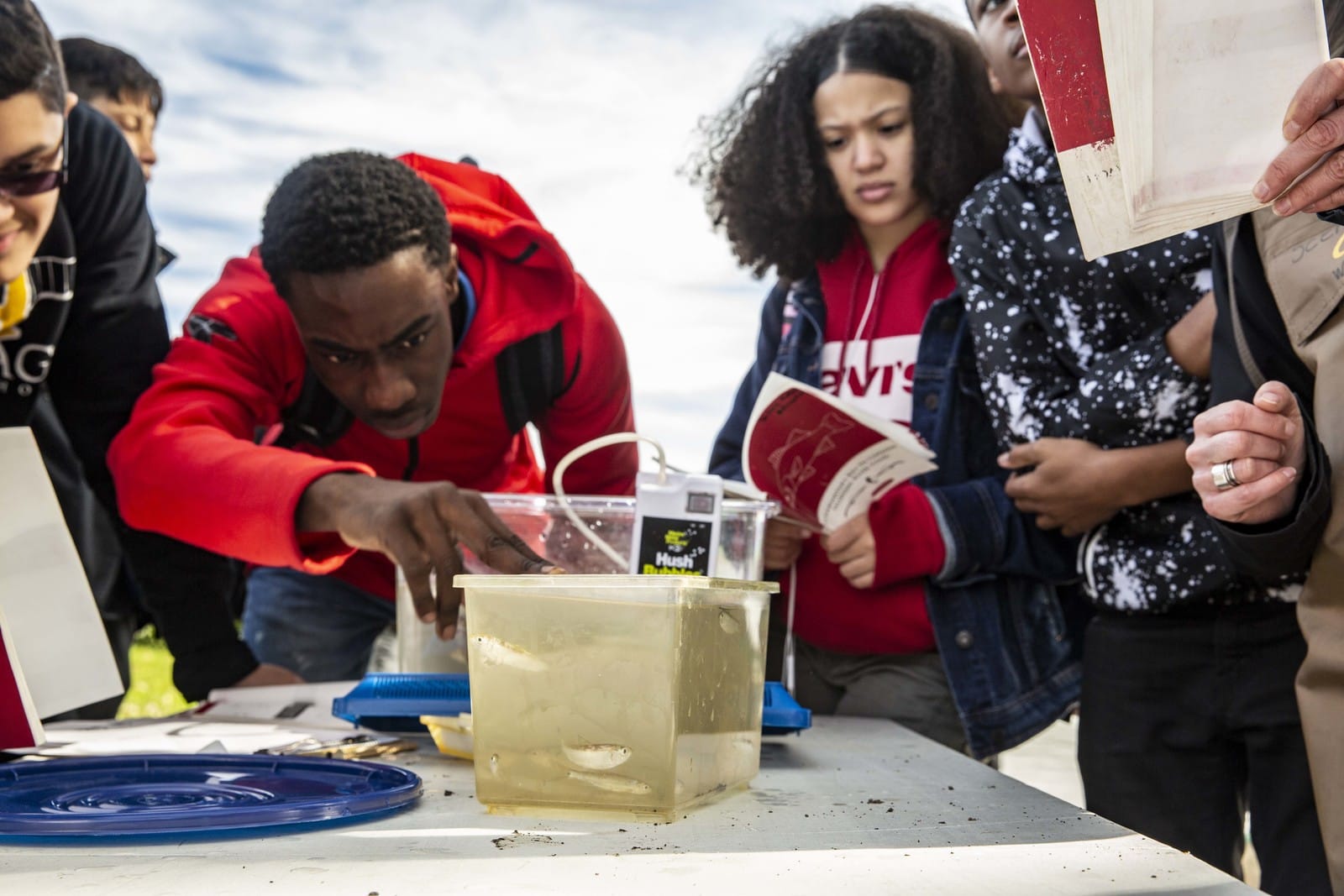

Stempel says that expanding experiential learning is one of the center’s key goals, particularly given the wide array of parks and preserves in the Hudson Valley managed by the state and nonprofit organizations such as Scenic Hudson, the Open Space Institute and others. “Those are groups that we want to talk to,” she says.

Two Dutchess districts, Rhinebeck and the City of Beacon, have announced their intention to join. Joseph Phelan, who retired as Rhinebeck’s superintendent in 2020, is one of the center’s two individual partners, along with longtime environmental educator Dorna Schroeter. Both Phelan and Stempel say they were inspired by what they experienced at the Drawdown Learn Conference at Omega in 2019 and the Youth Empowerment & Sustainability Summit at the Ashokan Center in 2020.

“Life-changing,” Phelan says of the time he spent around students and teachers. In his final school budget, he set aside sustainability funding that his successor, Albert Cousins, will use to join the center.

In a poetic twist, Beacon’s membership fee is being drawn from $10,000 in sustainability funds from a community renewable energy program the city joined in 2019. In an online poll, city residents were asked to designate the funds to one of four possible projects: local school projects, highway garage solar panels, electric vehicle charging stations, or wind- and solar-powered lights. A majority of residents said the funds should go to schools.

“We need to get our kids not to be depressed about the climate crisis, but empower them with good education,” says Jeffrey Domanski, a parent of Beacon students and the executive director of Hudson Valley Energy, a nonprofit that worked with the city on its Community Choice Aggregation electricity purchase program.

Beacon’s superintendent, Matthew Landahl, says he looks forward not only to the potential for curriculum development, but also to an expanded capacity for students to become engaged in a solutions-based approach to climate change.

“Now there is, beyond our district, a resource for our students to be tapped into, whether it is students in other districts or experts in the field through the center,” Landahl says. “When students get to be involved in something that gets them outside their classroom and with students from other districts, they really enjoy and are really engaged with that.”

School leaders acknowledge that launching a new climate education initiative in the middle of a pandemic might be counterintuitive when the focus has been so much on health and safety. But Landahl notes that the pandemic may, in fact, accelerate cross-district partnerships. The county’s school superintendents used to meet on a monthly basis, he says. Now they are meeting weekly.

“I feel like the level of collaboration between districts is really increasing,” Landahl says. “I know my colleagues 100 times more than I knew them in the past.”

Stempel says the planet’s viability and climate education are inexorably linked. “Any changes that are serious and long-lasting are going to happen because students stood up and said it needs to happen,” she says.