Tramping through a patch of woods in the Hudson Highlands between Beacon and Cold Spring, James O’Neill points out edible plants and mushrooms, explaining how to identify each, how to best prepare them, and even why, environmentally speaking, you should be eating them.

Garlic mustard, for example, is a green that can be eaten raw in salads, sauteed, or grated from the root like horseradish, and because it’s an invasive species that competes with native pollinators, picking it helps the local ecosystem.

“I believe that foraging can have a positive impact on the environment if done sustainably and mindfully,” O’Neill says. “It gets people out into their natural environment and, through plant identification, gets people’s minds engaged with the ecosystem they are a part of.”

Foraging guides like O’Neill can help residents and visitors of the Hudson Valley with discovering the region’s bounty of wild edible plants and mushrooms, as well as how those foods can be responsibly harvested.

(A few notes on responsible harvesting: The removal, including foraging, of plants is not allowed in Scenic Hudson parks. Foraging is also prohibited in New York State parks. Gathering wild food can create challenges, both collective and personal. Foragers should follow seven basic rules of foraging and avoid harming the local ecosystem. They also have to be careful about poisonous lookalikes and herbicide applications, and aware of some of the misunderstandings that foragers, including of people of color, are candid about potentially facing on the land.)

Bringing expertise on where and how to go about wild food-seeking safely, O’Neill leads foraging workshops in the Hudson Valley as part of his foraging service, Deep Forest Wild Edible, which also provides wild ingredients to both home cooks and pro chefs. Its two-hour workshops cover foraging basics, including plant and mushroom identification and preparation, as well as health and legal considerations, such as which areas are prone to contamination or may be restricted to foraging.

“I recommend beginners to start with a few easily identifiable species first — ones that do not have any poisonous look-alikes, such as ramps, garlic mustard, cattails, fiddlehead ferns, and stinging nettle,” O’Neill says. “These are all easily identifiable and have features that clearly will distinguish them from any nonedible species they could be confused with.”

While O’Neill holds state certification for identifying mushrooms, he’s gained his knowledge of foraging through a wide-ranging career that’s taken him from the forest into the restaurant industry and back to the forest again. After high school, the Newburgh native attended Paul Smith’s College in the Adirondacks in hopes of becoming a park ranger, but was turned off by bureaucracy. Instead, he entered the kitchen, eventually traveling to Prince Edward Island in Canada to join his cousin, celebrity chef Michael Smith, at The Inn at Bay Fortune.

“We had gardens where we grew much of our produce and all of our herbs, and we would tramp through the island forests in search of the abundance of wild mushrooms that grow there,” O’Neill sasys of his time at The Inn. “That was my first exposure to wild mushrooms that had any weight in the culinary ring.”

O’Neill isn’t the only professional forager and advocate in the Hudson Valley. Dina Falconi, author of Foraging & Feasting: A Field Guide and Wild Food Cookbook, is an Accord-based herbalist and educator who’s been foraging for more than 40 years. Falconi’s knowledge of the region’s wild edible plants and mushrooms has been earned from teachers, mentors and self-study. She shares it through her online class, “In the Wild Kitchen.”

“Get out there and engage the plant and fungal kingdom,” Falconi urges. “Spend time in nature and learn to distinguish ‘the wall of green.’”

Falconi suggests learning from an experienced forager, but also recommends that beginners explore online resources, too. Like O’Neill, she advocates foraging to connecting consumers with the source of their foods, which naturally inspires conservation and reduces reliance on unsustainable agricultural practices.

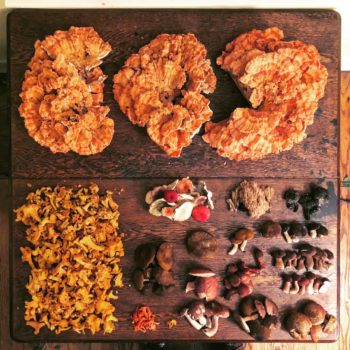

Assorted mushrooms

Baby mushroom

Golden oyster

Chicken of the woods, boletes and russula

Trametes versicolor (turkey tail)

Apios priceana

“As foragers, our relationship within nature — our complete interdependence — becomes crystal clear,” Falconi wrote in Foraging & Feasting. “It reconnects us to the exhilarating yet humble place within the web of life. With this comes the rewarding responsibility of caretaking the land and the plants that feed us.”

Beyond the environmental benefits, O’Neill also believes that these locally sourced wild plants and mushrooms could be the ingredients that best define the Hudson Valley’s regional cuisine — which currently, he laments, is mostly a smattering of trends from New York City.

“We are fortunate here in the Hudson Valley to have wonderful wild ingredients that would otherwise have to be shipped — chanterelles from the Chezch Republic, porcinis from France, morels from the West Coast,” O’Neill says. “We have all of these wonderful wild ingredients right here in our backyard. If we take the time and think to use what we have here, we can show the world that we’re a unique and bountiful region, with the best of the best, a truly solid contender in the global ring of famous regional cuisines.

“The best cuisines are doing just that — celebrating what they have right in their microclimate, not needing to look outside of their realm for ‘exotic’ ingredients that seem to bring a certain, maybe even forced, dazzle to a dish,” he continues. “Regional chef masters are using what is there, and I am very proud of what we have here.”