The poor, acidic, and shallow soil on top of the Shawangunk Ridge was never ideal for farming — but it offered a perfect medium for huckleberries and wild blueberries to grow. For a century of summers, from the 1860s into the 1960s, picking them was a major local industry that satisfied a craze for them throughout the Northeast. At a few spots in the ‘Gunks today, hikers can explore traces of the seasonal communities where the berry-pickers lived.

What the huck?

First, a bit about the huckleberry, a smaller and usually tarter distant cousin of the blueberry. There are a number of varieties across America, ranging from blue to red to black, with black common in the Shawangunks. All get their name from the English hurtleberry or whortleberry, altered to huckleberry around 1670. (Nope, no one knows why.) Adding to the confusion, pickers in the Shawangunks used the term huckleberry to refer both to huckleberries and blueberries.

Even those who’ve never seen or eaten a huckleberry are familiar with the name. Mostly, that’s due to Mark Twain’s American classic, The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn. Lighter-lit readers might know it as the title of Val Kilmer’s recent memoir, I’m Your Huckleberry. (In the movie Tombstone, Kilmer’s Doc Holliday said the line just before dispatching somebody with his gun. No one knows why on that, either.)

Huckleberries weren’t a flash in the pan — archaeologists have found that Indigenous peoples were eating them at least 11,000 years ago. In the Northeast, Algonquin women dried the berries and then pounded them into a powder that was mixed with meal to create a dish that tasted a lot like spice cake.

Shoes, stockings for the winter

In addition to providing food, “Huckleberries played significant parts in traditional legends,” notes one fascinating, in-depth account of their significance to Indigenous peoples like the Iroquois. “The harvest gathering times were causes of celebration and opportunities to visit friends and relatives not seen since the previous season. This was a traditional time of work to harvest the fruit for use during the rest of the year; however, evenings were reserved for celebration, oral histories, and legends.”

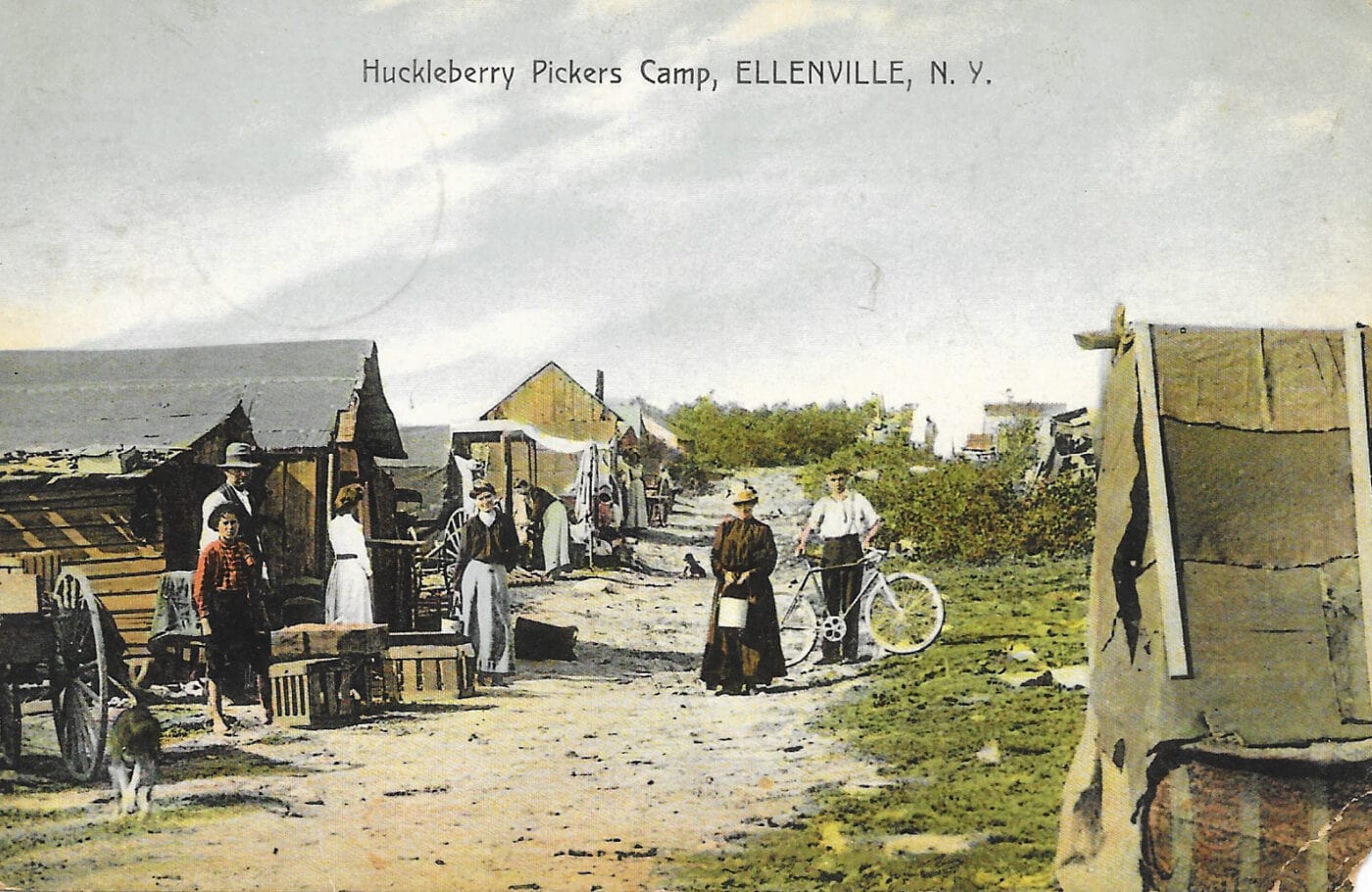

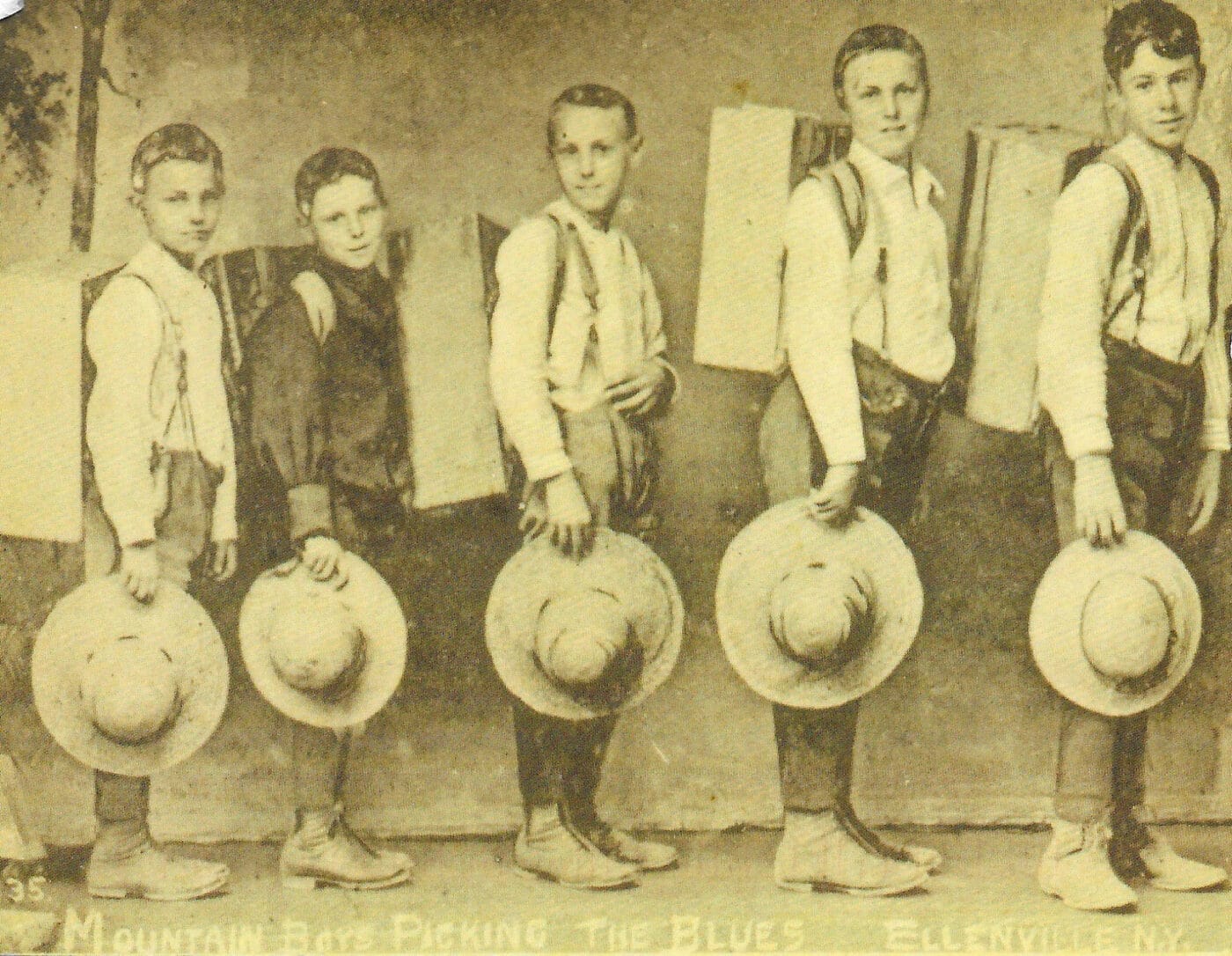

Introduced by Indigenous peoples to the huckleberries’ tastiness, colonists picked them for personal consumption. Beginning around the time of the Civil War, a booming demand for berries led to the birth of a commercial industry that drew hundreds of pickers — men, women, entire families — to the ’Gunks for the season, beginning with blueberries in July and huckleberries in August. Whether they arrived from homes at the base of the ridge or migrated from New York City or even further afield, the pickers lived in tarpaper shacks and tents close to the berries, which were said to be the sweetest in the East.

Many of their communities stretched out along the Smiley Carriage Road, which runs from Ellenville to Lake Awosting (and now traverses Minnewaska State Park Preserve and Witch’s Hole State Forest) or sat atop Sam’s Point, also part of today’s preserve. Wherever they lived, the Shawangunks pickers were squatters, trespassing on private land. But no one seemed to mind. They made do without electricity, running water, and bathrooms. Most cooked over open fires.

In the 1890s, the New York Times printed what may be the best account of the operations’ economic impact: “Few people at a distance from the huckleberry-growing country realize the real import of a big huckleberry harvest. It means shoes, stockings, and warm raiment for the coming winter and a thousand little comforts to the myriads of people, young and old, who swarm the mountains and upland meadows culling the wild and delicious fruit.”

The article goes on to note that the pickers earned six cents a quart for their harvest. That harvest consumed them seven days a week. The fruits of their labor were shipped to New York City as well as local resorts.

Living close to the land

Pickers walked from sunup to sundown in search of ripe berries. “You were out in the heat, on your hands and knees,” says John Stedner, interviewed in the short film The Huckleberry Pickers. Most people picked by hand, placing handful after handful in a tin bucket or hand-woven basket. Once full, its contents were poured into a large wooden backpack. Others used a contraption, known as a “knock-a-box,” to shake the berries off the low bushes, while a few resorted to a handheld rake. According to Marc Fried, author of The Huckleberry Pickers, the definitive account of summertime life on the ridge, a “serious picker” could harvest 20 to 40 quarts of berries a day.

At nighttime, as suggested by the subtitle of Fried’s book — A Raucous History of the Shawangunk Mountains — things could get a little out of hand in some of the camps owing to hard drinking (some pop-up stores supplied the liquor as well as necessities). By and large, however, as this brief history states, most pickers were “good … folk living close to the land.” They filled their evenings with storytelling, singing, and simply enjoying the mountain solitude.

Picker Virginia Ferguson, also interviewed in the film, recalls: “It was so peaceful and wonderful.” Ernie Babcock seconded her enthusiasm: “We had so many friends and had such a good time here, you didn’t think twice about going back.” According to Rebecca Howe, interpretive ranger at Sam’s Point, some people who pick berries there today continue a long tradition: “Their families have been doing it for over 100 years,” she says.

Berries, bears and snakes

Huckleberries thrive in conditions shaped by fire, which makes the soil more acidic and eliminates taller plants that keep light from reaching the sun-loving bushes. For that reason, pickers often intentionally set fire to parts of the ridge at the end of each season, causing a real headache for volunteer fire departments in surrounding towns. The sweetest berries arrive two years after a wildfire, says Howe.

Today, hikers can find an intact picker’s shack that belonged to a man named Blacky (the rest of the year a denizen of New York City), near the intersection of Mine Hole Road and Smiley Carriage Road. A collection of pickers’ pails also sits at the beginning of the aptly-named Huckleberry Trail. It takes less of a trek to see remains of shacks at Sam’s Point as well as picking artifacts in the visitor center.

After World War II, berry picking in the ‘Gunks witnessed a sharp decline, the victim of better-paying jobs and the advent of commercially grown blueberries, although it didn’t die out completely until the late 1960s. Of course, the best way to honor the memory of this long-gone industry is to pick — and eat — them. New York State law allows visitors to pick plants or fruits in state parks for “personal consumption” (in the case of berries, about a quart). Just watch out for bears and snakes; the former love eating huckleberries and the latter share the bushes’ habitat.

Pop the berries in your mouth straight off the bush, or take them home and make a cobbler or pie. “We’ve already had one staff member bake a pie, and it was delicious,” says Howe. “His recipe is tailored to the blueberries that grow here.” Whatever you cook with them, it’s guaranteed to cause a raucous sensation around the dinner table.

Visitors to Sam’s Point can enjoy a Berry Bonanza! from 10 a.m. to 3 p.m. on Aug. 7 and 8, 2021. Participants can sample huckleberries and wild blueberries, and create a container to gather them while enjoying a hike through the preserve.