Back in the days when people could count on the Hudson River freezing over nearly every year, skating on it was a popular pastime. In Newburgh, people took to it with particular zeal. As early as 1815, hometown skaters like Charles Payne (a Black man believed to be free even before slavery was abolished in New York State) were noted for their speed.

By 1891, a chronicle of the city declared: “It has been said that the history of skating — that is, speed skating — in this country, if ever written, must be written at Newburgh, which is now, and, our oldest residents say, always was, ‘the headquarters for fast skaters.’”

While that history never has been fully written — and details about its earliest participants are scant — there are some impressive (and fun) facts to recount.

Early skaters share strong river connection

What made Newburgh such a mecca for competitive skating, beginning with racers like Payne, Jacob June and John Decker? That’s hard to fully answer. What we do know: many of Newburgh’s earliest skating champions had a strong connection to the river.

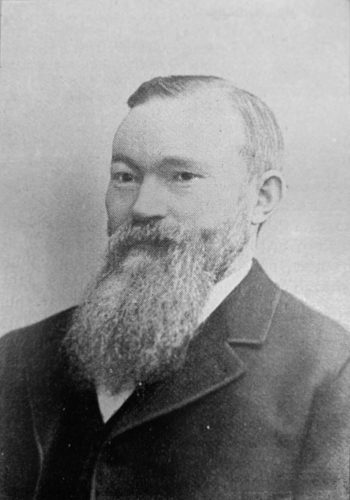

For example, Charles June, who earned renown for skating fast backward as well as forward in the 1840s and ’50s, captained sloops, barges and steamboats on the river for 60 years. Along with his skating prowess, he was a champion yachtsman and rower, like Timothy Donoghue, Sr., who took the crown from June as Newburgh’s fastest skater from the 1860s through the ’80s. An immigrant from Ireland and a Civil War veteran, Donoghue manufactured oars deemed the world’s best.

At the beginning, skaters in Newburgh and elsewhere simply raced against each other. Sometime in the mid-19thcentury, several skating enthusiasts asked Newburgher George Shaw, perhaps June’s fiercest local competitor, if they could time him over a quarter-mile course they’d laid out on the river. Shaw jumped at the opportunity despite the economic hardship. As he later reminisced, “We didn’t follow skating as a business, and when we took a half day off to skate it meant half a day off pay, too.” From that moment, the stopwatch became an essential component of speed skating.

At first, handbills distributed in nearby riverfront communities like Cornwall and Haverstraw attracted skaters and spectators to Newburgh. Prizes for the winners came from passing the hat. In the 1890s and early 1900s, the National Amateur Skating Association, organized in 1886, frequently hosted its national championships in the city. Races took place on the Hudson when ice conditions permitted and Orange Lake when they didn’t. These events drew skaters from throughout the Northeast, Midwest and Canada, as well as crowds of 5,000 and up.

Skating to Albany with the “Newburgh Cyclone”

It’s speed that earned Donoghue the nickname the “Newburgh Cyclone” — one account of his racing career says he won enough prizes to “decorate the wall of a room” — but he also excelled at endurance. His most awe-inspiring feat on the Hudson in this regard occurred during the winter of 1872. In the morning, he and a friend made a 30-mile excursion to Poughkeepsie and back. Later that afternoon, Charles June joined them for another jaunt — to Albany.

Donoghue later recalled that the distance from Newburgh to the capital via railroad is 84 miles. “As we had to cross the river from one side to another a number of times, looking for good ice, I think it made [our] distance more,” he judged. Subtracting time for 2 detours (to skirt cross-river ferry channels) and a 45-minute dinner break, Donoghue estimated it took the men 5 hours to reach Albany. He admitted their progress was favored by a “strong wind.”

(Photo: Wikimedia Commons / public domain)

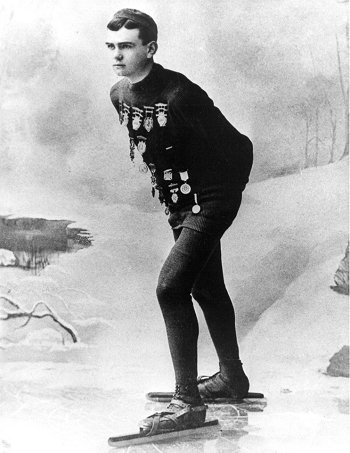

Three Donoghue children proved to be chips off the old block when it came to skating, with Joseph, born in 1871, far and away the best. After excelling at roller skating, he switched to the ice in 1887 and won the state championships at 1 and 5 miles. The next year he began competing in Europe.

Bringing home a world championship

In Amsterdam, Joseph lost the half-mile and mile races to his prime competitor, Russia’s Alexander Von Panschin. When it came time for entrants to line up for the 2-mile event, Donoghue smiled and said, “If I don’t win this time, the old man will be sending for me to come home.” He didn’t disappoint, as recounted in this dramatic account of the race:

“Then the word was given and the dozen skaters were off amid roars of applause. Twelve thousand waved their hands and shouted as they passed the half-way mark side by side, Joe swinging along with even, steady stroke, his legs moving with the precision of piston rods, and the Russian beside him, with arms swinging and face drawn as if he were unable to realize that the youngster at his side was actually gaining on him.

“Von Panschin appeared to be straining every nerve and muscle, while Joe, with his arms folded behind his back, might have been out for a pleasure stroll for any effort he seemed to make. Down the home-stretch they came, and Joe drew away from his famous rival inch by inch until there was a distance of two yards between them. Joe never lost his head, and won by seven seconds, making the fasted time on record, 6m. 24s.”

(Photo: Wikipedia / public domain)

Back in Amsterdam 3 years later, Donoghue won the quarter, half, mile and two-mile races and, with them, the title of speed skating’s world champion. He was the first American to wear this crown — and the last until Eric Heiden in 1977. At home in Newburgh later that winter, Donoghue also skated his way to the national championship, capping off a career year.

What was the secret of Joseph’s success? His father attributed it to using skates with longer than normal blades. They allowed him to keep up a steady speed without swinging his arms, cutting down on wind resistance. Joseph simply folded his arms behind his back, which in itself sounds exhausting. But more than one writer attested to Donoghue’s physical strength and staying power, which once allowed him to skate 100 miles in 7 hours and 11 minutes. That remains a world record.

Broadening participation in speed skating

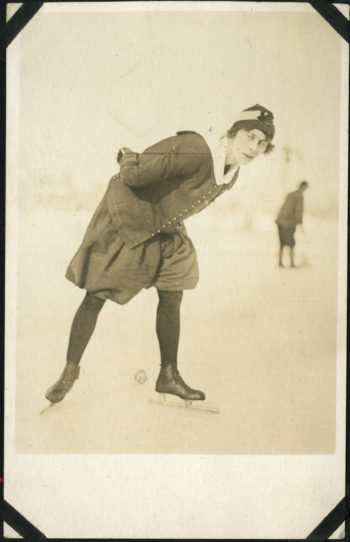

While women had long enjoyed skating as a recreational pastime, as many Currier and Ives prints can attest, they didn’t compete in races until well into the 20th century. When Newburgh women finally got the chance, they equaled the winning ways of the city’s men. In the 1940s and ’50s, Mary Lynch, Caroline Crudele, Joan Russell and Gwendolyn Dubois brought home medals from important eastern and national championships. Unfortunately, other than newspaper accounts highlighting their on-ice accomplishments, little is known about them.

Henry Uihlein Scrapbook)

Perhaps the finest woman speed skater on the Hudson lived in Westchester’s Hastings. A secretary by day, Elsie Muller-McLave practiced on the river in the evenings and on weekends. She earned local, national and international titles, and represented the U.S. at the 1932 Olympics, the debut of women’s speed skating (as a demonstration sport). The first U.S. women to win gold medals at the Olympics were Anne Henning (at 500 meters) and Dianne Holum (1,500 meters) in 1972.

Other than Payne, there is limited record of other African Americans from Newburgh competing in speed skating. That can be attributed to historic segregation, discrimination, and socioeconomics. Making many winter sports more open to all has been an ongoing challenge given the high costs of participation and lack of broad access to top training facilities.

In recent years African Americans have made majors breakthroughs in speed skating, beginning with Shani Davis. In 2002, he became the first African American to represent the U.S. at the Winter Olympics. In subsequent games, he won 2 gold medals. Since then, U.S. speed skating has continued growing more diverse. Erin Jackson and Maame Biney became the first Black women to skate at the Olympics in 2018, when the U.S. fielded its most diverse team ever at the games.

Both Elsie Muller-McLave and Joseph Donoghue have been enshrined in the U.S. Speed Skating Hall of Fame, which was based in Newburgh from the early ’60s to the mid-’90s. (Today, it’s located in Utah.) This program attests that Newburgh also continued hosting major championships as late as 1964. Since then, the city’s fame as the “cradle of speed skating in America,” as the program boasts, or of the Hudson’s role in boosting the sport, seem to have vanished with the ice that once brought so many skaters and spectators down to the river.