Centuries-old apple varieties that were almost pushed out by industrialization have started to get popular again in the Hudson Valley as farmers and cider makers recover more robust, flavorful fruits.

While loads of Gala or Honeycrisp may pop to mind when the “U-pick” signs start cropping up, dozens upon dozens of varieties flourish in the region. Some can be traced back generations to the efforts of early orchardists and homesteaders. It’s these apples, commonly referred to as heirloom varieties, that modern enthusiasts are working to bring back from the brink.

Why? For one, they taste a lot better.

“Heirloom varieties are interesting because a lot of them were not bred with shippability in mind, or appearance,” says Martin Bernstein, CEO of Abandoned Hard Cider. “A lot of them were just bred for, or became popular, because some farmer thought it was a really cool apple and it tasted really delicious. Whatever it was that that family wanted to make — be it cider or pie, dried apples, or fresh apples — that particular apple appealed to them.”

Before the 20th century, growers were more concerned with hardiness and taste than looks. Apples with higher acidity and tannin content might be too tart when fresh, but they made for better ciders.

Growing perfect apples and replicating them en masse isn’t as simple as planting the seeds from your prize tree and letting time work its magic, though. Nope, apple trees can be unpredictable. Geeking out here for a sec: Their seeds are heterozygous, meaning they contain a mix of dominant and recessive genes from the parent plants. And the resulting seedling may or may not produce fruits with the desired characteristics.

To stay ahead, crafty farmers figured out a way to bypass the uncertainty, taking cuttings from the best trees and grafting them onto other seedlings to produce genetically identical offspring. In other words, clones.

The ability to fine-tune the fruit in this way led to thousands of apple varieties, each carefully selected for specific traits. Orchardists “continued to clone and share their scion wood [for grafting],” Bernstein explains, until there were, for a time, more than 15,000 named varieties in the U.S. Eventually, those numbers dwindled as characteristics like shippability and appearance took priority.

You can get notes of cucumber, and candy apple, and pineapple, and all sorts of tropical notes.

Martin Bernstein, Abandoned Hard Cider

But now, with the U.S. deep in the midst of a hard cider renaissance, the older, more interesting varieties have regained their appeal.

As Ryan Burk, head cider maker at Walden’s Angry Orchard, has said, “Each heirloom apple found in the U.S. today carries a unique piece of American history and offers a complex flavor experience that translates into unexpected cider.”

“You can get notes of cucumber, and candy apple, and pineapple, and all sorts of tropical notes,” Bernstein says. “This year we made a really cool single varietal with an old New York heirloom called Golden Russet, which is pretty acidic but not as mouth-puckering. That turned out to be a much more rounded sort of honeyed mouthfeel. It was just a very different expression.”

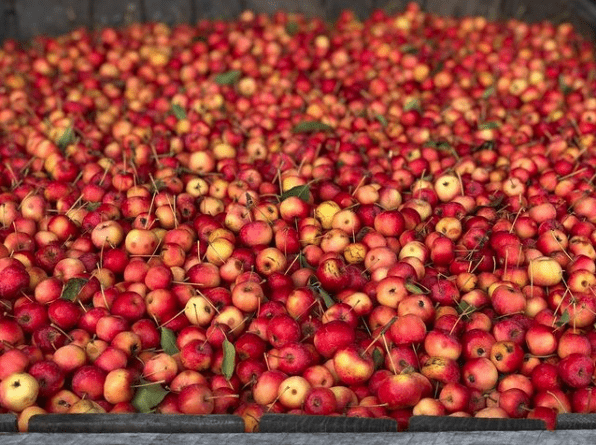

Montgomery Place Orchards, in Red Hook, advertises more than two dozen antique apple varieties, including the Jonathan, Golden Russet, and the beloved Esopus Spitzenburg, a local variety that goes all the way back to the 1700s. (The latter is also Abandoned CEO Bernstein’s all-time favorite apple.) As the Montgomery team puts it, they are “the apples your grandparents and parents remember as if it were a dream.”

At Black Diamond Farm over in Ithaca, you might give a rarer variety a try; the orchard and cider house boasts 150 specialty varieties, most of which are heirloom. Locust Grove Fruit Farm, too, which has long offered U-pick and farmers’ market distribution, has been prepping its own cidery to showcase its heirloom varieties. That’s set to open this year. And for its Brooklyn Cider House ciders, Twin Star Orchards even grows heirloom crabapples, like the celebrated Manchurian Crabapple.

Varieties like Jonathan, Golden Russet, and the beloved local Esopus Spitzenburg are “the apples your grandparents and parents remember as if it were a dream.”

Montgomery Place Orchards

Abandoned Hard Cider, on the other hand, headed by Bernstein and partner Eric Childs, isn’t focusing solely on heirloom varieties, which all come from clonal stock. The team’s real mission is hunting down feral varieties that have developed in the wild from seed after homesteaders long ago abandoned their orchards, working with landowners and leading foraging excursions throughout the Catskills and Hudson Valley to find these rare treats. Those generous enough to lend the apples on their land get cider in return. It’s a win-win.

Venturing beyond the current standard, blander varieties is worthwhile for both producers and consumers. “The flavor is superior,” Bernstein said.

Diversity also helps the plants survive against disease, pests, and environmental changes. For an orchard made up of entirely cloned plants, those threats can be devastating. “We get excited when they make discoveries,” USDA apple curator Ben Gutierrez told NPR recently in response to the recovery of several apple varieties thought lost to time. “Because it’s a push for apple conservationism.”

Today, there are still several thousand apple varieties out there — you just have to know where to look. Luckily, hundreds of orchards in New York State alone have heirloom varieties in the mix. Check out the options near you at Apples from New York — you just might find your new favorite fruit.