As far as Hudson Valley mountain rails go, the Mount Beacon Incline Railway seems to get all the glory. From 1902 to 1978, it lifted some 3.5 million passengers to the 1,540-foot summit. There — at least for a time — a hotel, restaurant, and dance hall competed with stunning views for their attention. For part of the five-minute trip, the railway reached a gradient of 74%, making it the world’s steepest funicular (or cable railway).

Today, hikers who start trekking up the mountain in what is now Scenic Hudson’s Mt. Beacon Park follow the railway’s course for a bit. And the ruins of its powerhouse near the summit contains rusting remnants of its machinery.

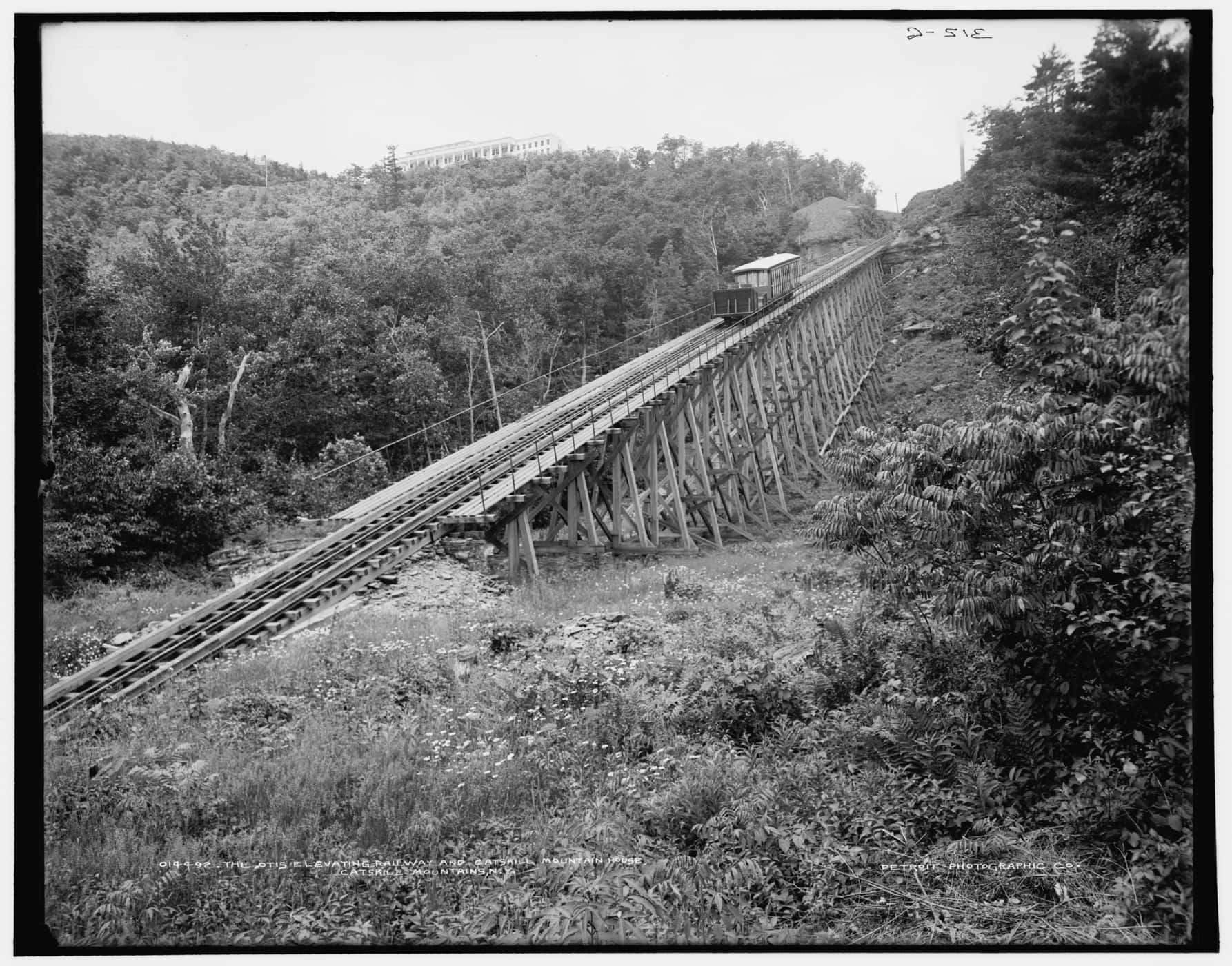

But there was an even older funicular in the region — the Otis Elevating Railway — and it had a lasting impact, helping open up the Catskills to major tourism. Upon its opening in 1892, Engineering News hailed it as “the longest cable incline railway in this country, and with but few exceptions the longest in the world.”

It may have been a technological marvel, but its creator hated it.

The Otis Elevating Railway was the brainchild of Charles Beach, owner of the Catskill Mountain House, which for much of the 19th century was the region’s fanciest hotel. A who’s who of luminaries, including three U.S. presidents, stayed there. Thomas Cole and other Hudson River School artists painted it, and writer James Fenimore Cooper included it on his shortlist of America’s must-see destinations (along with Niagara Falls and Lake George). Standing today at the hotel’s former site, on a mountaintop ledge that affords 180-degree vistas of the Hudson Valley, you see what made it so special.

“A desecration of nature“

But by the 1890s, Beach had a problem — increasing competition from the grand Kaaterskill Hotel nearby and a growing number of smaller resorts all built closer to railroads that delivered guests from the steamboat dock in Catskill practically to their front doors. Reaching the Catskill Mountain House required a stagecoach ride of up to five hours, all over shaky roads. Seeing the need to improve access or lose clientele, Beach came up with an ingenious solution in the Otis Elevating Railway.

But taking this step made Beach angsty. According to someone who knew the hotelier (and is quoted by Roland Van Zandt in The Catskill Mountain House, the definitive book about the hotel), Beach considered any destruction of the forest “an act of vandalism,” and he “would not permit the cutting of a single tree on any property under his control except when absolutely necessary.” So you can imagine his dismay at what it would take to erect the funicular — cutting (in Van Zandt’s words) a “7,000-foot gash” between North and South mountains. It was “a desecration of nature,” said the acquaintance of Beach, to which he “never became fully reconciled.”

But desperate times call for desperate measures. So Beach hired the Otis Elevator Company, headquartered in Yonkers, to design the funicular. Otis also built the 2,200-foot Mount Beacon Incline Railway, and the two contraptions operated similarly. Engines turned a set of cogwheels (like those in the powerhouse ruins on top of Mount Beacon). The cogwheels drove a cable attached to two railroad cars. One went up, counterbalanced by another heading down. Unlike at Beacon, much of the Otis Elevated Railway tracks stood off the ground, atop wooden trestles.

“A novel and delightful experience“

Beginning near a station on the Catskill Mountain Railway, the funicular hoisted passengers — 75 to 100 per car — up the 1,630-foot mountain. In 10 minutes, they arrived a short walk from the Catskill Mountain House’s famous piazza. An 1894 guidebook described the trip’s visual treat: “As the train ascends, the magnificent panorama of the valley of the Hudson, extending for miles and miles, is gradually unfolded; while the river itself, like a ribbon of silver glistening in the sun, and the Berkshire Hills in the distance seem to rise to the view of the passenger.”

The Otis Elevating Railway had its desired effect — not only luring more overnight guests to the Catskill Mountain House, but turning it into a day-trip destination as well. According to another guidebook, published in 1893, “large bodies of excursionists now rush up the mountain two or three times a week, dine at the hotel, scramble around the park, and rush back again at night, tired and noisy, but happy.” Thanks to the funicular (and speedier steamboats), travelers from New York City could reach the Catskill Mountain House in three or four hours rather than a full exhausting day.

According to Van Zandt, the Otis Elevating Railway also played an important role in “democratiz[ing] the institution of the summer vacation.” By making the Catskills accessible to anyone who could afford the funicular’s 75-cent ticket, more people became aware of the mountains’ beauty, peacefulness, and extraordinary recreation. In a way, it helped to usher in the Borscht Belt era.

Sadly, the Otis Elevating Railway wouldn’t be around to witness this surge. Along with the Catskill Mountain Railway, it closed in 1918 and was sold for scrap to manufacture armaments for World War I. The deep-pocketed guests who once filled the rooms of the Catskill Mountain House and spurred creation of the funicular had begun to prefer the even wilder surroundings of the Adirondacks, accessible via expanding railroad lines. The hotel hung on until 1941, its dwindling roster of guests arriving by car. (The crumbling building was burned down by the state in 1963.)

Today, the “gash” created by the Otis Elevating Railway is still visible but overgrown. Charles Beach might be happy to know that the natural beauty of his beloved mountains is gradually being restored.