As a child, Boston filmmaker Kevin Ferguson spent nearly every summer in the Catskills among a clan of Irish immigrants and first-generation natives in what was known as the Irish Alps. What the Borscht Belt was to Jews, the area around East Durham was to the Irish.

“It was such a bizarre place,” Ferguson says. “The town was completely transformed into an Irish town in summers. It’s where my parents met, and where many Irish couples met, on the dance floor. It’s where I learned to dance. It was charming and odd in so many ways, and hard to describe in words.”

Its midcentury heyday

When Ferguson’s mother emigrated from County Cavan to America in 1950, her first address was a small boarding house in East Durham owned by her sister, called Mullan’s Mountain Spring Farm. Ferguson says that Irish immigrants had been visiting the area, which was previously predominantly German, since the late 1800s.

Many thought the landscape reminded them of the Ould Sod, what with its lush, soft, rolling green hills. In the 1930s and ‘40s, with the Depression and then war in Europe, many Germans sold their boarding houses and businesses to those of Irish descent, and the Irish Alps were truly born.

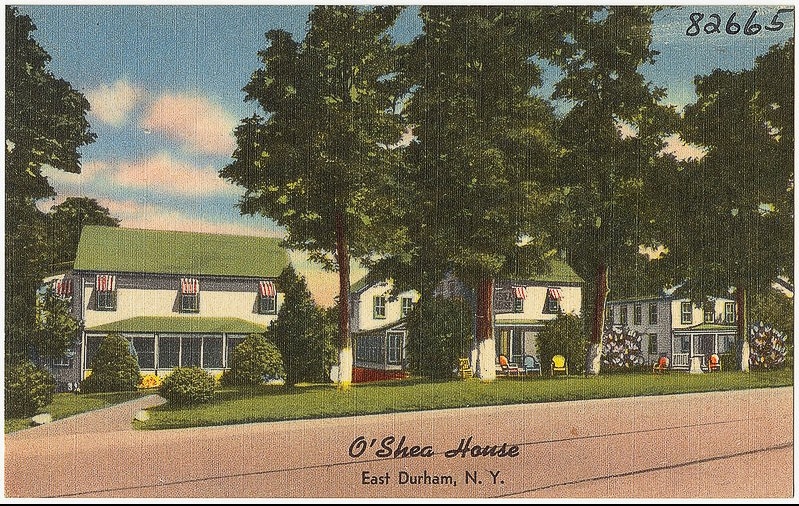

The towns of Leeds, South Cairo, Oak Hill and East Durham offered boarding and sustenance at places with evocative names like the Shamrock House, Gavin’s Golden Hill, Kelly’s Brookside Inn, McKenna’s Irish House, and Erin’s Irish Melody. In the summer, city dwellers looking to escape the heat and dirt headed upstate for the clean mountain air.

‘What county are you from?’

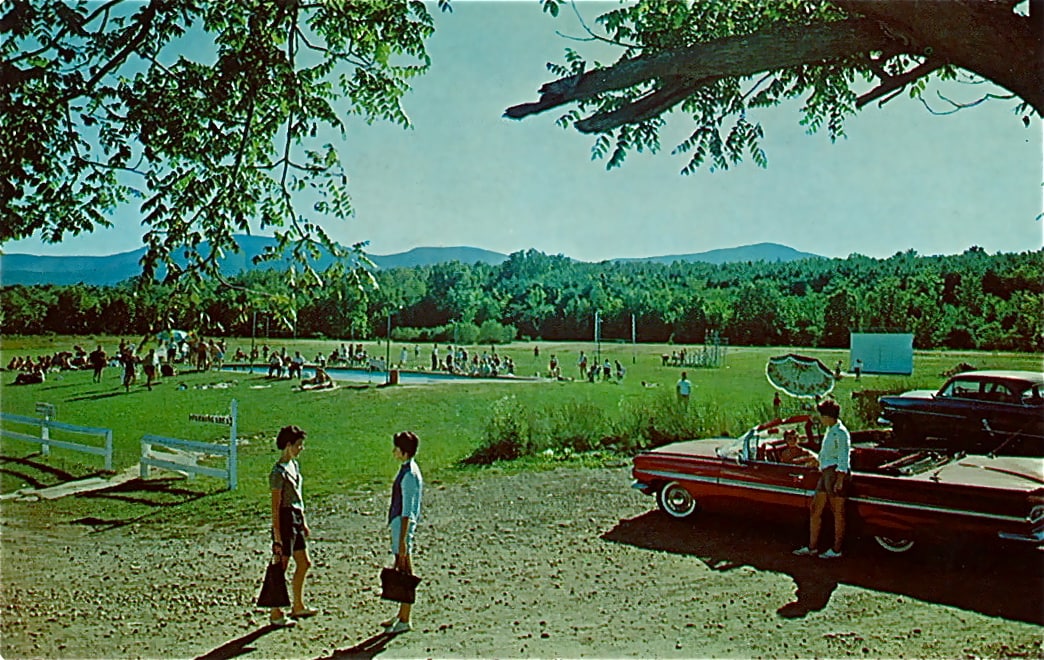

As with the Borscht Belt, the Irish Alps hit its heyday after the war, from the 1950s through the early 1970s. In 1960 there were upwards of 40 Irish-run hotels or boarding houses in the area, Ferguson says, filled each summer with Irish families singing, dancing, and playing music. “Leeds reminds me of a village in Ireland, with one main road [and] a few storefronts. It’s only a block long, but in the day there was a street car,” he says. “That’s how much activity there was.”

The union organizer Michael Quill played a big role in that. His New York transportation workers union, begun in the 1930s, helped a lot of Irish workers earn better pay and more time off. Many had been spending any free time at the Rockaways, a smorgasbord of Irish, Jewish, and Italian retreats. Now, they could travel farther, for longer, and be with their own.

“It was an opportunity to be among themselves, without judgment,” he says. “There was a lot of prejudice in New York, and upstate, and like every ethnic group it created its own community. You could go there and the conversation had already started. You don’t have to explain yourself. You don’t ask, ‘How are you?’ You ask, ‘What county are you from?’”

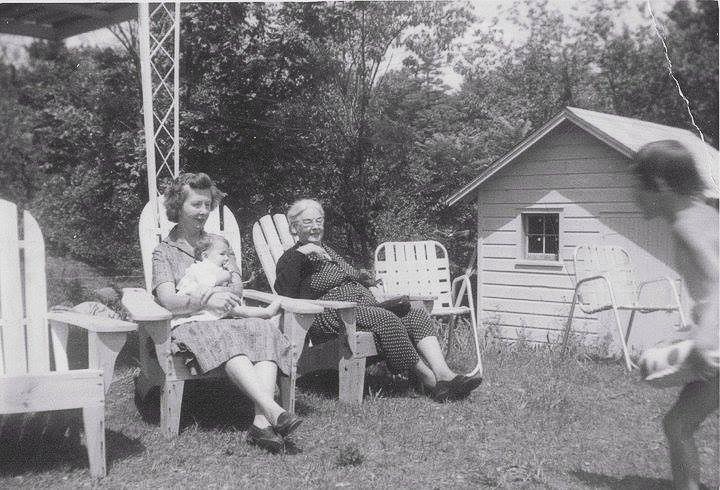

A family affair

Ferguson’s parents met in 1955. She was working at the hotel. “As family, you work,” he says. “If you are remotely related, you work. Everybody pitched in.” His father was an Irish American on vacation. They met on the dance floor. “Many marriages were made up there on the dance floor,” he says. “It was a known thing.” If new arrivals happened on the scene, the bandleader might announce their presence, what county they were from, and if any parent had a child who’d like to meet a nice Irish lad or lass.

Every summer, Ferguson’s mother would wait tables, his father would tend bar and sing, and other family members would chip in wherever needed. By his teens, in the mid-1970s, Ferguson worked six days a week, washing dishes, mowing lawns, painting fences, carrying luggage. “It was a lot of work,” he says, “and a lot of play.” In those free-range days, kids could roam the woods and fields.

Ferguson stopped going upstate in the 1980s, when he went to college. By then, lots of others had stopped going as well. Discrimination had lessened, air travel had cheapened, and just as the Borscht Belt lost its Yiddish, the Irish Alps lost its Gaelic.

Ferguson’s old haunt became the Blackthorne, one of just a handful of resorts that still thrive as vacation spots but now for a much more diversified clientele. “The Blackthorne has a strong Irish following during Irish Arts Week, and a few other weeks, but back in the day it was all Irish,” he says. “Now they have a motorcycle rally and spaghetti wrestling. That wasn’t happening when my aunt was alive.”

Hungry for Irish heritage well beyond St. Patrick’s Day? The area hosts its annual East Durham Irish Festival in late May.