April usually marks the beginning of the shad run in the Hudson River, when adult males and females begin journeying from their haunts in the Atlantic Ocean — somewhere between Canada’s Bay of Fundy and the Virginia coast — to spawning grounds in the freshwater of the estuary’s upper reaches. For about 6,000 years, this migration also occasioned a fishing, and feeding, frenzy. American shad tasted so good they were bestowed with a Latin name, Alosa sapidissima, that means “delicious.”

Sadly, shad prove the adage that you can have too much of a good thing. Decades of overfishing contributed to a serious decline of this species that sustained Indigenous people for thousands of years, prevented George Washington’s Continental Army from starving and fed Americans during World War II. In 2010, New York State banned fishing for American shad, halting one of the region’s most historic industries and ending a valley tradition — the Hudson River shad bake — that brought people down to the river each spring.

Hope springs eternal that American shad will make a comeback. Statistics since the ban haven’t been overly promising, with the Atlantic States Marine Fisheries Commission stating bluntly in its 2020 assessment that “the stocks of American shad in their native range along the North American east coast are likely currently at all‐time lows.” But if any fish deserves a revival, it’s this largest member of the herring family.

Blessed with beauty and endurance

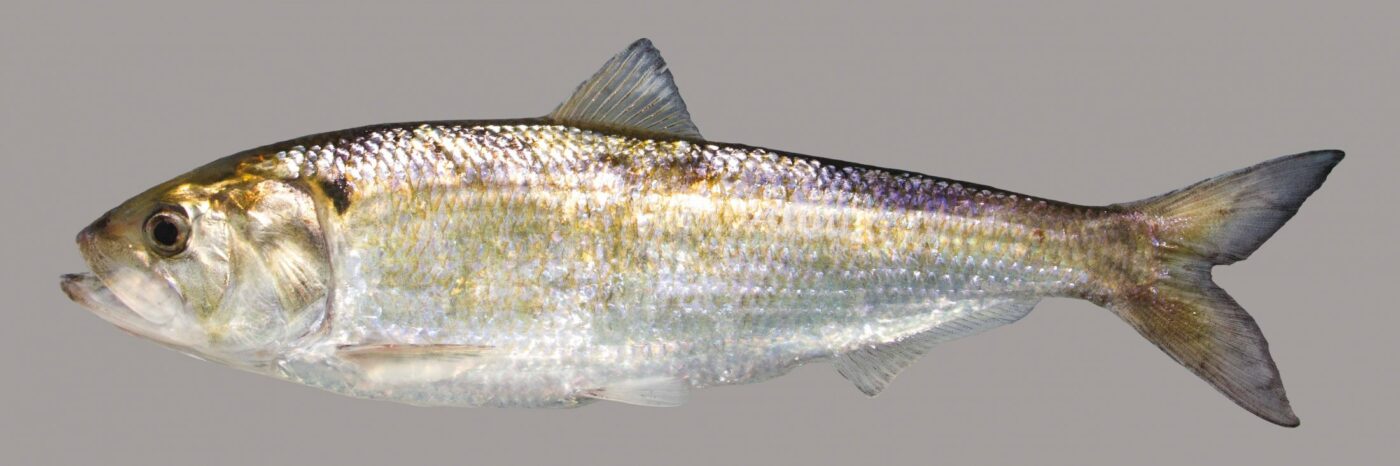

In terms of looks, American shad is a stunner — 20-24 inches of sleek, silvery beauty, with a metallic green tint on the back and a touch of lavender on the tail. These fish also get props for endurance. Remarkably capable of adapting from saltwater to fresh, which requires a change in their breathing and kidneys, they travel hundreds of miles to reach their spawning destinations in the Hudson, on the sandy shoals and shallows between Kingston and Troy. If not for the impediment of the Federal Dam at the latter, they’d probably venture even farther — in Florida, they’ve been spotted 375 miles up the St. Johns River. While shad feed on plankton and shrimp during their incoming journey, they swim home without eating a bite, relying solely on fat reserves for energy. For good reason, they’ve been compared to marathon runners.

The first to take advantage of American shad as a food staple in the region were Indigenous peoples like the Lenape, who timed their fishing according to the serviceberry. Also known locally as shadbush, this understory shrub or small tree blossoms in mid-April, concurrent with the shad’s spawning run up the Hudson. (The fish have their own “alarm clock.” They don’t begin their migration until the river’s water temperature reaches 50-55 F.) When the shadbush’s white flowers appeared, the Lenape and other Native American peoples along the river would set up their weirs, net-like obstructions woven out of reeds, on poles staked in the water.

It’s thought that the way the region’s early European settlers cooked shad — affixed to wooden planks placed near a hot, open fire and cooked for 5-6 hours — derived from earlier, Indigenous techniques. Mohicans also placed shad fillets on racks to dry in the sun, while the colonists packed the fish in barrels with salt. Both methods allowed the meat to remain edible for months.

American shad have been called the “savior fish” of the American Revolution. Just as the Continental Army faced starvation after the harsh winter it endured at Valley Forge in 1778, the fish happened to make an extraordinarily early spawning run up the nearby Schuylkill River. According to historian Henry Emerson Wildes, “So thick were the shad that when the fish were cornered in the nets, a pole could not be thrust into the water without striking fish. The netting was continued day after day until the army was thoroughly stuffed with fish.” During World War II, when offshore fishing became too dangerous, river shad picked up the slack to fill Americans’ stomachs.

Facing a perfect storm of challenges

Commercial shad fishing on the Hudson, which began in the mid-1700s, went through several cycles of boom and bust into the 20th century. Overfishing may have been a culprit, although researchers aren’t certain. At the industry’s high point, around 1940, some 400 operations cast their nets into the river each spring. When historian (and Scenic Hudson co-founder) Carl Carmer published his classic book on the Hudson in 1939, he wrote that “between two and three million pounds of shad are taken from the Hudson each year.” When you consider that American shad typically weigh no more than 7 pounds (and often less), that means each annual catch yielded somewhere between 285,000 and 430,000 fish.

Into the 1980s, American shad seemed to be holding their own in the Hudson, then things went sour for them. The last 6 fisheries operating in 2009 hauled in 3,792 fish, once a so-so haul for a single fisherman. They’ve been done in by a perfect storm of challenges. Overfishing in the Atlantic (shad don’t help themselves, swimming right into nets), loss of habitat along the river and decreased access to it, an increase in predators (including various varieties of bass), and climate change all have contributed. The local spread of invasive aquatic species like zebra mussels and European water chestnut also pose a challenge for the fish by depleting oxygen levels in the water.

A goal of the ongoing Comprehensive Hudson River Restoration Plan, which Scenic Hudson played a role in creating with fellow environmental groups and state and federal agencies, is to “restore the signature fisheries of the Hudson River estuary to their full potential, ensuring future generations the opportunity to make a seasonal living from the estuary’s assets and to fish for recreation and consume their catch without concern for their health.” Achieving it will take additional research, funds and cooperation extending beyond the valley’s boundaries. Sadly, at the moment, time is not on the side of the American shad.