Beavers figured prominently in North America’s past — they were appreciated by Indigenous people for millennia, and are the main reason the Dutch chose the Hudson Valley to settle. Yet they could play an even bigger role in our future. For the latest in our #WildlifeLove series, rethink the misunderstood beaver.

Like so many of us, North American beavers (Castor canadensis) are the descendants of immigrants. The first of their species arrived here from Eurasia via the Bering Land Bridge, which linked Asia and today’s Alaska, around 7 million years ago. Also journeying across was the giant beaver, which resembled its smaller cousin but rivaled a black bear in size, sported a thin tail and didn’t have sharp teeth. These two creatures coexisted until the Ice Age, about 11,000 years ago, which killed off aquatic plants and in turn the giant beavers that subsisted on them.

The saving grace for North American beavers was — and is — their four incisors, two up, two down, that allow them to chomp through trees. If a beaver smiled at you, you’d notice that the incisors are orange, because they contain lots of iron. This makes them very hard. The teeth also grow at a rapid pace. They have to, in order to make up for the erosion that occurs from the mammals’ constant gnawing.

Essentially, trees provide “one-stop shopping” for beavers. They help furnish habitat (wetlands created by damming streams with felled logs), homes (conical lodges that sleep anywhere between five and a dozen beavers) and food. Beavers eat the bark and especially the cambium, the soft, nutritious layer beneath the bark. A well-fed male beaver can weigh up to 70 pounds, making it North America’s largest rodent.

Of course, a beaver’s most distinguishing feature is its tail, which resembles a canoe paddle. It, too, is multi-purpose, providing an alarm system (slapping it on the water alerts fellow beavers and scares off predators), balance (for standing on their short hind legs to chew through a tree) and a rudder (for steering through the water). Ungainly on land, beavers can swim up to 5 mph thanks to their back webbed feet, which resemble scuba fins.

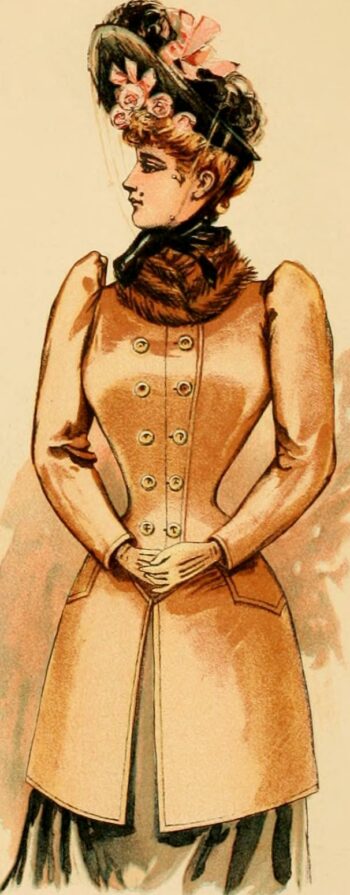

trimmed with Seal Plush, Reveres and Cuffs,

and Astracban Cloth (Image from Deutsch & Co.

(NY) fall/winter 1891)

So much for the beaver’s biological quirks, none of which interested early colonists. What made Castor canadensis the national symbol of Canada and earned it pride of place on the City of Albany’s official seal? In a word, hair. The beaver possesses two types — a long outer layer that provides waterproofing, and underneath that a layer of tightly packed, shorter hairs that furnishes warmth. In the 17th century, both also satisfied two desperate needs in Europe. The long layer was perfect for lining winter coats, the shorter one for making felt hats. You could say that while climate change killed off the giant beaver, style nearly did in its cousin.

Doomed by European fashion

Prior to the great beaver hunt in North America, Russia had been supplying enough pelts to meet the demand for high fashion across Europe. But by the 1600s, the Eurasian beaver had been hunted nearly to extinction. A new supply was sorely needed. Enter the Dutch in the Hudson Valley. In 1614, they established a fur trading post at present-day Albany (for a time called Beverwyck, or beaver village). So wild was the craze for beaver — from 1626-1632, the Dutch shipped 52,584 pelts back to the Netherlands; later, exports approached 46,000 pelts annually — that by 1640 beavers had been wiped out from most of New York.

The colonists relied on Indigenous people to provide the pelts. (Interestingly, European traders preferred receiving used beaver coats, which made it easier to prepare the skins and separate the hairs.) Indigenous people brought beaver pelts to trade for knives, axes, needles and other merchandise. Payment depended on the quantity and quality of the furs.

Increased demand and dwindling supplies eventually pitted one European nation against another (Dutch vs. French, English vs. French), and caused even more conflict among Indigenous peoples. As beavers disappeared from tribes’ traditional hunting grounds, they ventured further afield, encroaching upon the lands of other groups. The series of violent clashes that occurred in the latter half of the 17th century have been called the Beaver Wars.

Beavers continued being a hot commodity across North America until 1900. At that point, their numbers had dwindled to a paltry 100,000, down from an estimated 400 million at the dawn of European colonization. Environmental journalist Ben Goldfarb, author of the fascinating book Eager: The Surprising, Secret Life of Beavers and Why They Matter, labels this one of “humanity’s earliest crimes against nature”

Return of the “ecological Swiss Army knife”

Over the last 120 years, beavers have made an astonishing comeback. If you conducted a census of them today, it would probably surpass 15 million. In the Hudson Valley, they’re now prevalent in many bodies of water, including Louisa Pond at our Shaupeneak Ridge preserve. (The best time to spot these shy creatures is just after dawn or just before dusk.)

This resurrection is good news not only for beavers but other animals — including us. Why? Because beavers are what’s known as a keystone species, an organism on which an entire ecosystem depends. Goldfarb goes so far as to call them “an ecological Swiss Army knife.”

The wetlands created by beavers sustain many fish, amphibians and other aquatic mammals, as well as plants. These wetlands also benefit humans in coutnless ways. They filter out pollutants that otherwise would flow downstream. They keep the ground moist, preventing the spread of wildfires. By causing water tables to rise on agricultural land, they can increase farmers’ productivity. From a climate standpoint, beaver-made wetlands store run-off and stormwater, limiting damage from increasingly frequent major weather events, and they act as carbon sinks. The latter is especially important — wetlands make up 3% of the world’s land area, but sequester 30% of its soil carbon.

Admittedly, flooding caused by beavers can be a challenge in some cases, but most do far more good than harm. There’s even a growing “beaver believer” movement on the West Coast, where Indigenous groups and others are calling attention to the essential role beavers can play in maintaining healthy landscapes. For these reasons and many more, Eager ends with a succinct plea: “Let the rodent do the work.”