Described by one writer as the “Bob Dylan and Madonna of her generation,” poet Edna St. Vincent Millay (1892-1950) was partly responsible for promoting the “roar” in the Roaring Twenties, both through her groundbreaking (and to some, shocking) work and bohemian lifestyle. The two are best exemplified by the lines from “First Fig” (1920):

My candle burns at both ends;

It will not last the night;

But ah, my foes, and oh, my friends—

It gives a lovely light!

Often overlooked, however, is Millay’s lifelong passion for nature and how a retreat in Columbia County’s Berkshire Hills, her home for 25 years, allowed her to indulge in it.

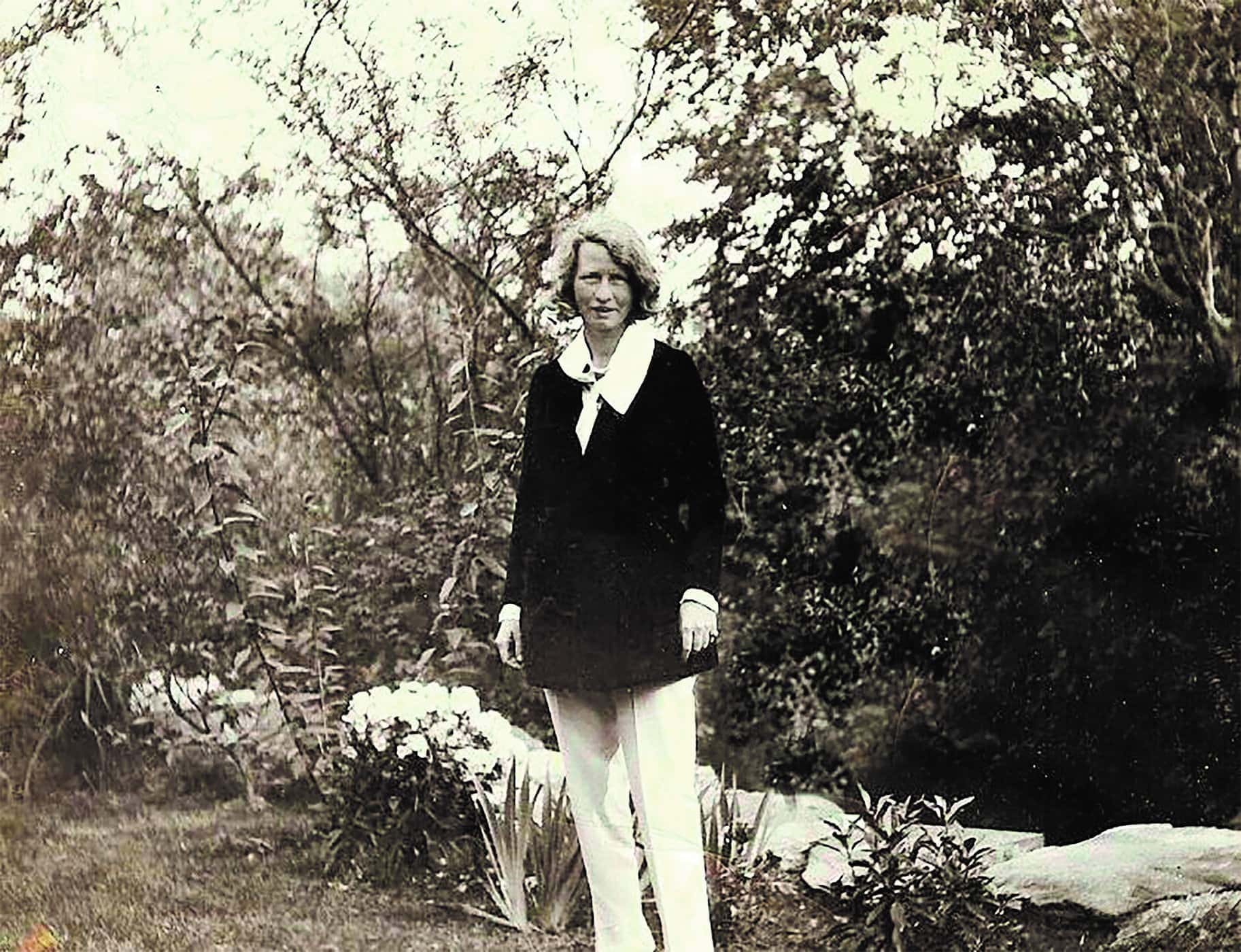

The first female poet to win the Pulitzer Prize (in 1923), Millay veered away from Victorian mores and morals in her work. Instead, she highlighted women as independent and sexual beings. The public latched onto her rebellious spirit, and her books flew off the shelves. “Her national popularity and bestselling status seem astounding to us now,” says Holly Peppe, Millay’s literary executor.

As Robert Duncan, who wrote and filmed a documentary about Millay, put it, “There was a time when every thinking woman in America wanted to be just as independent and brave and sexy as Edna St. Vincent Millay.”

Born in 1892, Millay grew up poor and largely fatherless in Maine, and achieved fame at age 19 with her long poem “Renascence.” After graduating from Poughkeepsie’s Vassar College, she beelined for Manhattan’s free-spirited Greenwich Village, where she wrote poetry, plays, and journalism while becoming a fixture in the heady social and sexual atmosphere. She became known for her many trysts with the literati of the day.

A world away from adoring readers

But Millay was not at home in the city. She missed engaging with nature, which had provided solace during her childhood. “As a girl, Edna spent hours alone by the sea and in the garden with her mother, who taught her the names of flowers, plants, and medicinal herbs,” says Peppe. One of her most quoted poems, written at age 15, begins “Oh, world! I cannot hold thee close enough!”

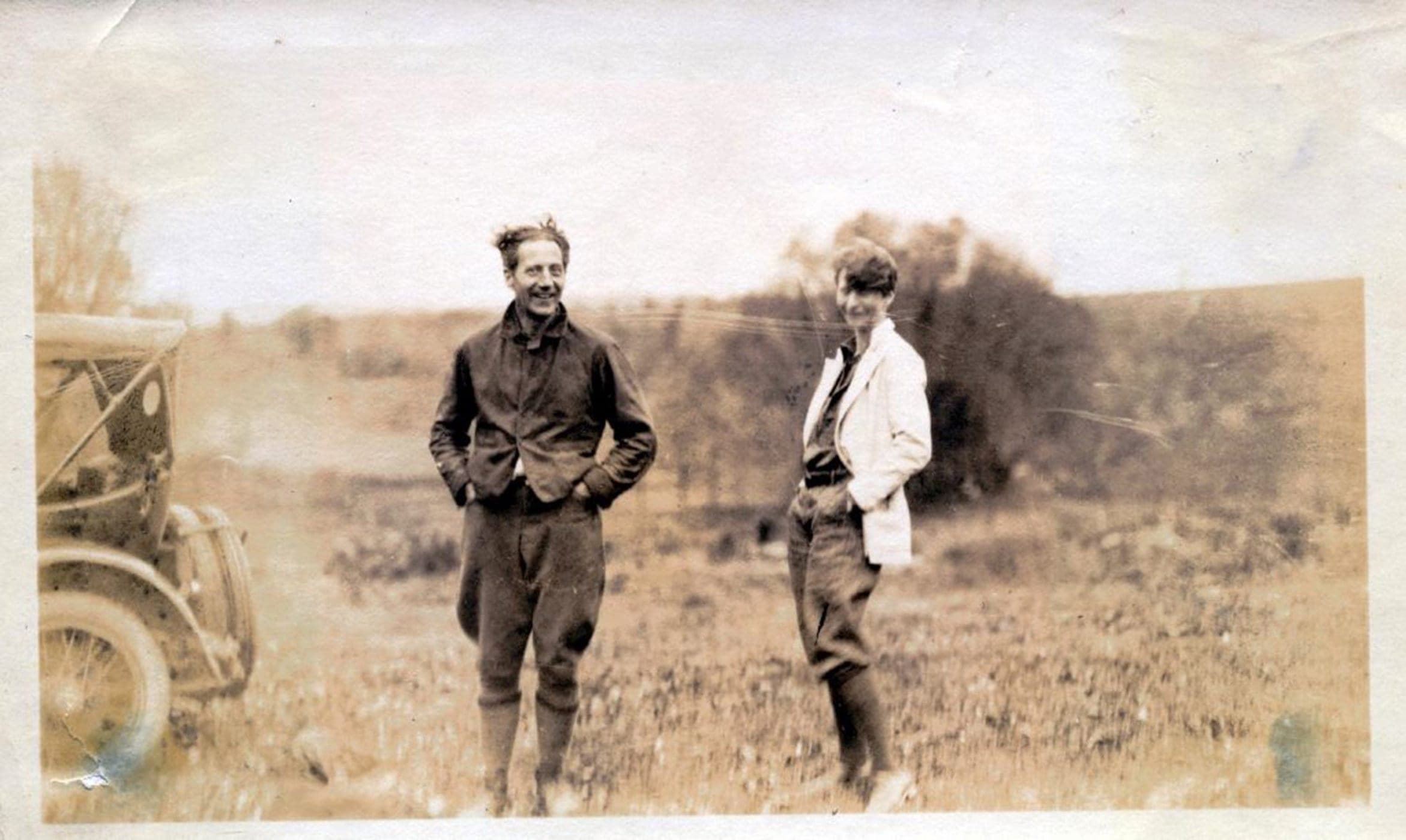

In 1923, Millay met and married handsome Dutch businessman Eugen Boissevain, and after a round-the-world honeymoon, she wanted to escape from the chaotic city for a quiet place to write. So, in 1925, she found a place in the rural town of Austerlitz where she could once again tap nature as her inspiration.

For $9,000, the couple purchased a colonial-style house and 300 surrounding acres, a former blueberry farm. (They later bought more land, more than doubling their acreage.) Millay named her new home Steepletop, after the steeplebush, a wild, pink-flowering shrub that still grows in meadows above the house. According to Duncan, “The bohemian poet who had scandalized America was settling into the upper middle class.”

Adds Peppe: “Moving to Steepletop was critically important to her life and her writing. It was her sanctuary, a world away from adoring readers where she could concentrate and work.”

Peppe notes that Millay’s “deep, deep connection to the land” at Steepletop was very much a hands-on affair. Indeed, her diaries (published in spring 2022) are filled with descriptions of outdoor chores — hours of joy, not drudgery. “Eugen & I worked all day digging & transplanting the snow-ball bushes that had budded themselves from the old tree, & raked & burned the driveway circle & other odd jobs. Most lovely day,” she writes in one entry.

Another makes clear that rural life did nothing to dampen her boldness: “I must never let the clumps of striped grass get any bigger than they are now … did all my weeding without a stitch and got a marvelous tan.”

“One of the loveliest places in the world”

Millay also observed nature with a keen eye. She kept detailed lists of flowers, plants, and birds. From a chair by the window in the house’s “withdrawing room” (a large living room with twin grand pianos), she kept track of birds feasting at her feeder. “She runs a hotel for birds,” Eugen remarked about his wife. “She’s up and at it every day before dawn.”

Although Millay had the means to expand the house — at the height of her fame, she earned $300,000 annually (about $5.3 million today) — she chose instead to create a series of outdoor “rooms” for personal pleasure and entertaining. “She loved being outdoors. Surrounded by natural beauty, she was in her element,” says Peppe.

The property’s al fresco spaces, separated by stone walls and hedges, included a sunken garden, rose and iris gardens, a bar, a spring-fed swimming pool, and a tennis court. The couple’s invited guests would breathe fresh air, skinny dip — and, it was said, water the flowers with gin.

But perhaps most importantly, Steepletop gave Millay poetic inspiration. In the small pine writing cabin, a short walk uphill from the main house, the sights and sounds she experienced each season found their way into her resonant verse. “Her imagery was primarily based on nature, and for a poet, there’s nothing more telling than your main source for imagery,” explains Peppe. Rare is the Millay poem that doesn’t contain a reference to nature or wildlife — a sleeping fawn, falling oak leaves, purple phlox, a spiderweb.

The Edna St. Vincent Millay Society at Steepletop has worked tirelessly to maintain the poet’s house as it was at the time of her death in 1950 (a little over a year after her husband passed away). It was assisted by the poet’s sister, Norma, who lived in the house from 1950 until her death in 1986 and left intact Millay’s personal belongings, including her library and clothing.

In January 2025, the society announced that it had partnered with Scenic Hudson, the state Department of Environmental Conservation (DEC), and the Land Trust Alliance (LTA) to permanently conserve the estate’s remaining 200 acres of meadows, forests, and wetlands, potentially setting the stage for increased access for visitors to explore the same natural treasures that fueled Millay’s creative genius. “We’re thrilled to have partnered with Scenic Hudson,” says Vincent Elizabeth Barnett, the society’s president. “This is an important milestone in our continuing efforts to protect and preserve Millay’s home, land, and legacy.”

“While visiting Steepletop,” adds Peppe, “many people feel Millay’s presence lingering in the house and on the property that she described, in a letter to her mother, as “one of the loveliest places in the world.”