Shortly after Franklin and Eleanor Roosevelt moved into the White House in 1933, leaving behind the family’s beloved home on the Hudson River, Elizabeth “Lizzie” McDuffie arrived there as well. Hired as a maid, McDuffie was actually a college graduate whose personal warmth — and determined advocacy — made her an important early voice for civil rights. Not long after being hired as part of the Roosevelts’ all-Black household staff, she boldly told the president that she intended to act as his “SASOCPA,” or “Self-Appointed-Secretary-On-Colored-People’s-Affairs.”

The Roosevelts’ record on race is mixed — something the Franklin D. Roosevelt Presidential Library is exploring in an unflinching new exhibit, “Black Americans, Civil Rights, and the Roosevelts, 1932-1962,” running through the end of 2024. Many of the issues McDuffie advocated around are covered in the exhibit.

The child of Georgia sharecroppers, McDuffie earned a bachelor’s degree from Morris Brown College in Atlanta, but still found employment opportunities limited to housekeeping. For 32 years she worked as a maid for an Atlanta family, earning at best $15 (about $230 in today’s dollars) per week. The White House position became available when First Lady Eleanor Roosevelt, breaking with tradition, insisted on an all-Black domestic staff and hired McDuffie, along with her husband Irvin as FDR’s valet.

McDuffie had a knack for reviving the president’s spirits, which sagged under the weight of the Great Depression and World War II. More importantly, as a result of the kinship that developed between them, she became the president’s eyes and ears in the African American community. While those in charge of FDR’s schedule tried to limit Black people’s access to him, she made sure their voices and concerns reached the Oval Office.

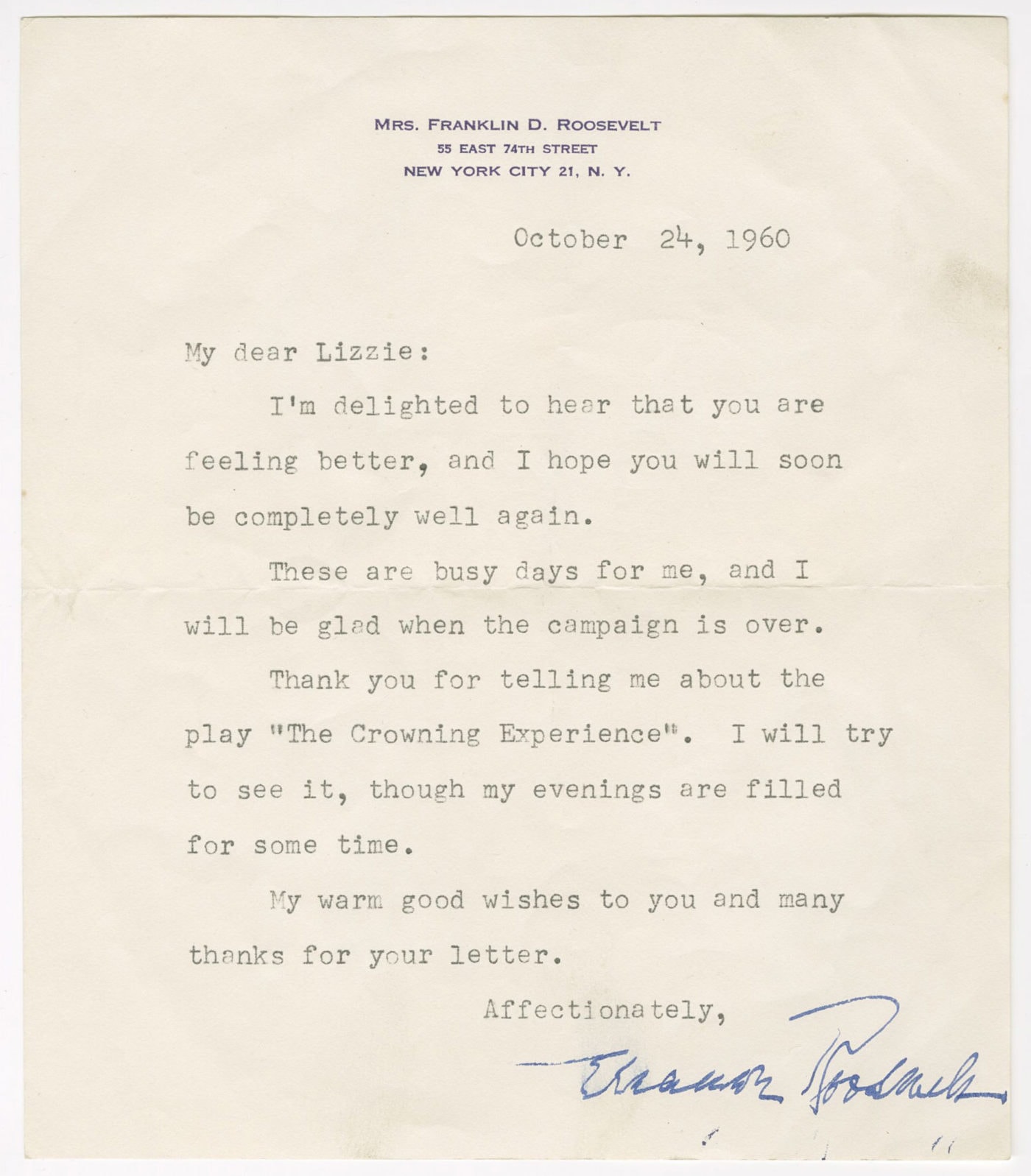

Since she often worked behind the scenes, in a self-directed role, public words about McDuffie are often limited, even in records of the civil rights movement. And while photographs of her are also scarce, her impact was significant.

Undertaking a “small crusade”

Elizabeth McDuffie was a breath of fresh air in the normally staid White House, refusing to temper her outgoing personality. According to Lillian Rogers Parks, who served as a maid under four presidents, “Lizzie treated FDR like one of her own family, kidding him and teasing him by kissing the bald spot on top of his head.” FDR ate up the attention, says Rogers, going so far as to nickname McDuffie “Doll.”

McDuffie leveraged their chumminess and FDR’s trust in her — she and Irvin were the only two members of the domestic staff granted free access to his bedroom — to raise more serious issues with him. In an unpublished memoir titled The Back Door of the White House, she called herself the “unofficial liaison between my race and the President.”

McDuffie seemed to get results in her self-described “small crusade.” Among her victories was convincing FDR to pardon three Black World War I veterans imprisoned for allegedly taking part in a riot. After the men’s release, NAACP head Walter White wrote her that “a large part of the credit for this should go to you for your persistent efforts.”

Behind-the-scenes “couriers”

Both McDuffie and her husband also proved invaluable in relaying reports about pervasive discrimination in FDR’s New Deal programs, especially the Works Progress Administration and Civilian Conservation Corps.

People across the country wrote the McDuffies, trusting them to pass their issues on. And as one historian writes, “Black leaders…realized that even though [White House Press Secretary] Stephen Early blocked them from getting information and requests to the president through normal channels, the McDuffies were glad to act behind the scenes as couriers to both the president and First Lady.”

Thanks in part to the news that came through this “back channel,” some modifications were made to the New Deal’s racist policies. It also probably helped spur FDR to issue Executive Order 8802 in June 1941. Dubbed the “Second Emancipation Proclamation” and recognized as “the first time since Reconstruction that the federal government had acted to explicitly protect the rights of African Americans,” it prevented racial and ethnic discrimination in the federal government and the nation’s defense industry.

While some historians have argued that FDR could have done more for African Americans, McDuffie never doubted his sincerity. In her memoir she writes that he “was democratic without posing and a true friend to the Negro race without paternalism.”

McDuffie also worked for change in other, more overt ways. She spoke out in favor of protesters’ demands in 1938, after 10,000 Black women rioted in Washington against limitations in New Deal programs that prevented them from earning living wages, limited their access to government relief programs and denied them Social Security benefits. Later, at Eleanor Roosevelt’s urging, she helped organize the United Government Employees, a union that represented lower-paid workers.

Quiet, deliberate and courageous

Throughout, McDuffie didn’t neglect her housekeeping duties. So important was she considered in this regard that Eleanor Roosevelt recruited her to help maintain the household at Springwood, in Hyde Park, N.Y., when King George VI and Queen Elizabeth visited in 1939. And she was present in Warm Springs, Georgia, when FDR died there on April 12, 1945.

Earlier that very day, McDuffie played presidential spirit-lifter for the last time. After FDR asked if she believed in reincarnation, she replied she wasn’t sure — but if she did come back, she wanted to be a canary. “The President looked at her 200-pound frame, threw his paper down, and burst out laughing,” reads an account. “Lizzie McDuffie would never forget that: the President with his head thrown back, his eyes closed, laughing and exclaiming — as she had heard him do 100 times — ‘Don’t you love it? Don’t you love it?’”

McDuffie passed away 20 years later. Her contributions to the civil rights movement have not been forgotten entirely. In an essay celebrating the 150th anniversary of the signing of the Emancipation Proclamation and the 50th anniversary of Dr. Martin Luther King Jr.’s “I Have A Dream” speech, both in 2013, writer Denise VanLanduyt also paid tribute to McDuffie’s “quiet, but deliberate, work [that] gave activists the ear of the leader of the free world.

“She too, like President Lincoln and Dr. King, was courageous in her pursuance of liberty and equality for all.”

Scenic Hudson has protected lands critical to preserving views from Springwood, now the Home of Franklin D. Roosevelt National Historic Site and one of the region’s prime tourism destinations. As a result, visitors today can be inspired by the same vistas that compelled FDR to reflect during a stressful moment in his presidency that “All that is within me cries out to go back to my home on the Hudson River.”