(Photo: United States National Library

of Medicine / public domain)

“Dreams can be made to come true,” said Dorothy Lavinia Brown, who achieved her aspirations by becoming the first African American female surgeon in the South, among other important accomplishments. While Brown spent her adult life in Tennessee, the Hudson Valley is where she first started to dream and, perhaps more important, found encouragement.

Brown’s inauspicious beginning certainly didn’t portend a bright future. Five months after Brown’s birth in 1919, her mother placed her in Rensselaer County’s Troy Orphan Asylum. It would be her home for the next 13 years.

“A place of last resort”

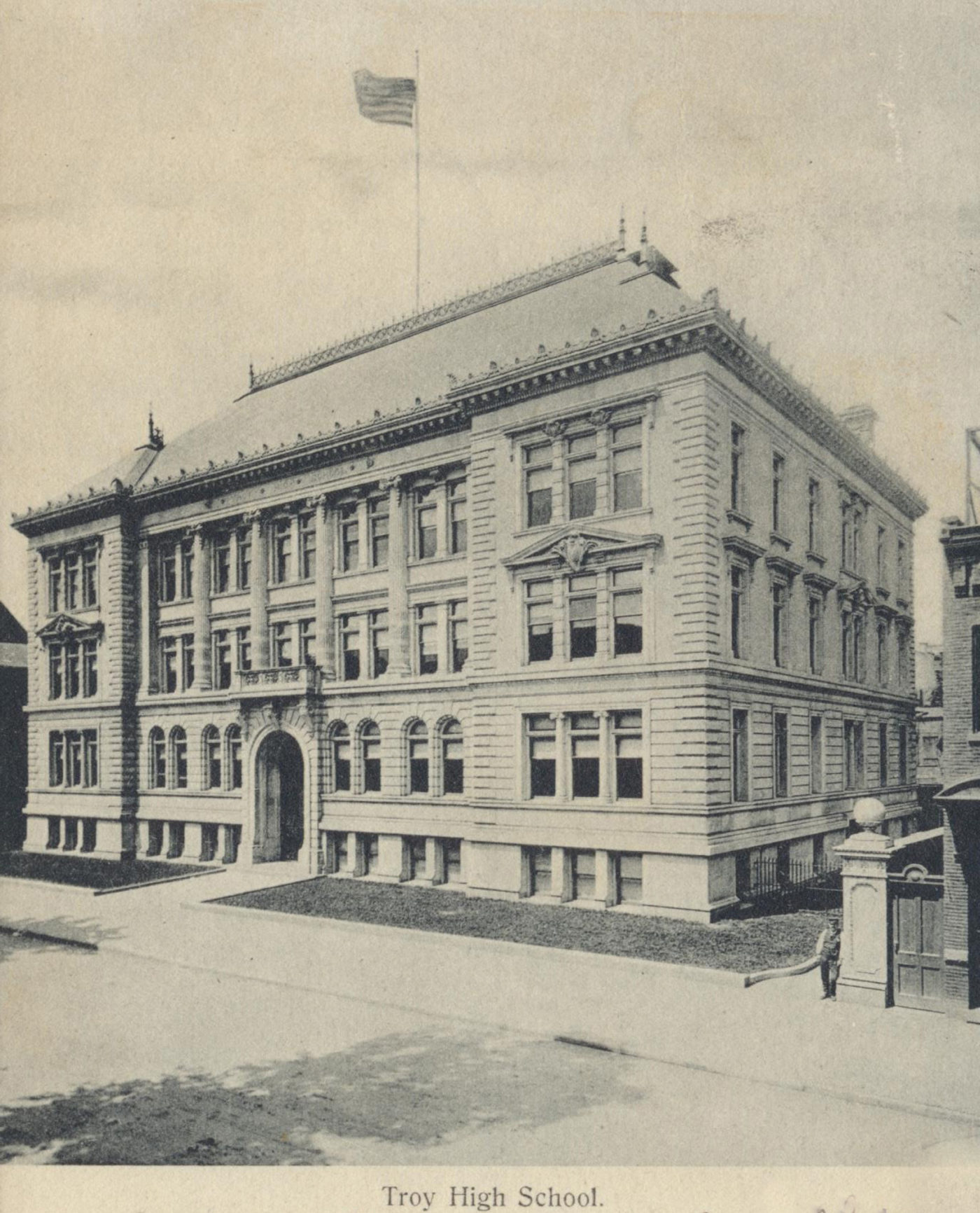

Nicknamed “the house on the hill” by locals, the orphanage filled a Gothic-style stone mansion on Troy’s Spring Street. According to a description in the Albany Times Union, back then it “was a place of last resort after a family became overwhelmed, financially or emotionally…. Being dropped off there left a social stigma, a shameful secret rarely discussed or buried for generations.” To get their children to behave, exasperated Troy parents often threatened them with banishment to the ominous-looking institution.

One woman who spent time in the asylum later recalled her experiences to the Times Union reporter. According to her, life there was hardly Dickensian but definitely regimented. Clad in a gingham dress sewn by one of the institution’s matrons, Brown would have been expected to complete daily housekeeping chores along with schoolwork. When a bell announced mealtime, she would have to march into the dining room and wait to sit simultaneously with her cohort. Meals were served family-style and eaten in complete silence, with dessert withheld from anyone caught speaking. Aside from these activities and mandatory attendance at Sunday chapel, the 100 or so youngsters enjoyed time outdoors on the asylum’s playground or in nearby parks.

At last: encouragement, security, support

Brown seems to have left no reminiscences of her years at the asylum, except for a single incident: She often said her dream of being a doctor originated with the comforting care she received there following a tonsillectomy. But by her actions, Brown made it obvious she preferred life at the orphanage to the alternative. On as many as five occasions, her mother reclaimed her. Each time, the girl ran away and made a beeline back to Spring Street.

Brown left the orphanage for good at age 13 and once again reunited with her mother. For a time, she held a series of menial jobs. Fortunately, her employer at one of them — a woman for whom Brown served as a mother’s helper — encouraged her to return to school and keep striving for a career in medicine.

Inspired, Brown ran away from her mother one last time and enrolled in Troy High School. When the principal discovered she was homeless, he arranged for Brown to live with city residents Lola and Samuel Wesley Redmon, who “became a major influence…as a source of security, support, and enduring values,” recounts one biography. Buoyed at last by a loving and stable home life, Brown graduated valedictorian of her class.

“Not hard, but durable”

At this point, Dorothy Lavinia Brown’s connection to the Hudson Valley ended, but the dream ignited there did not. Thanks to a 4-year scholarship awarded her by local Methodists, she earned a B.A. in 1941 at North Carolina’s Bennett College (this time graduating second in her class). After working in a defense plant to support the war effort, she entered Meharry Medical College, in Nashville, Tennessee, receiving her M.D. in 1948.

Brown had one more dream: to be a surgeon, unheard-of for a woman (let alone an African American woman) in the South. Most residency programs refused to admit her. Only men could handle the rigors of performing surgery, they claimed. Finally, she secured admittance into the 5-year residency program at Nashville’s Meharry and George W. Hubbard Hospital, and came through it with flying colors.

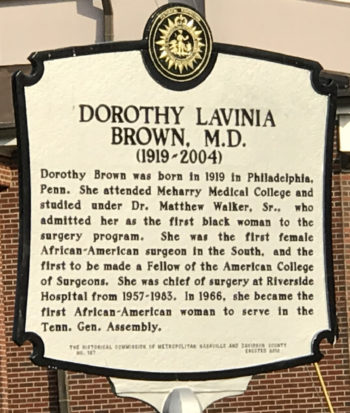

From 1957-83, Dorothy Lavinia Brown — “Dr. D,” as she was fondly known — served as chief of surgery at Nashville’s Riverside Hospital, clinical professor of surgery at Meharry Medical College and educational director for the Riverside-Meharry Clinical Rotation Program. She was the first African American woman to be made a fellow of the American College of Surgeons.

Interested in politics, Brown also became the first African American woman to hold state office in Tennessee, winning election to the Legislature in 1966. During her term, she successfully pushed for passage of the Negro History Act, requiring Tennessee public schools to conduct special programs during Negro History Week to recognize African American achievements. In addition, she became the first single woman in Tennessee to adopt a child (whom she named Lola, after her foster mother).

(Photo: Duane Marsteller / www.hmdb.org)

Brown once was asked what enabled her to persevere through so many hardships. Her succinct response: “I tried to be…not hard, but durable.” Also inspiring her was the knowledge that she could be a role model — “not because I have done so much, but to say to young people that it can be done.”

By the time Dorothy Lavinia Brown died in 2004, she’d come a long way from Troy’s “house on the hill,” the place where her dreams began.