As thousands of men went off to fight in the American Revolution, many women kept the home fires burning — which was always demanding work, but even more labor-intensive in that age, and doubly so during wartime. Some wives opted to join their husbands on the march as camp followers, earning money by performing chores for the troops. (They were a constant thorn in the side of Commander in Chief George Washington, who felt they hindered the Continental Army’s mobility.)

But a few women took part in active combat — including two who fought in the Hudson Valley, where so much of the war played out. Deborah Sampson went undercover to join the fray, while Margaret Corbin was unexpectedly thrust into battle. And then there’s Sybil Ludington, memorialized in Putnam County as the region’s Paul Revere.

Sampson, Corbin, and Ludington underscored that heroism is gender-neutral. They also serve as inspiration to the 70,000+ women in the U.S. military today.

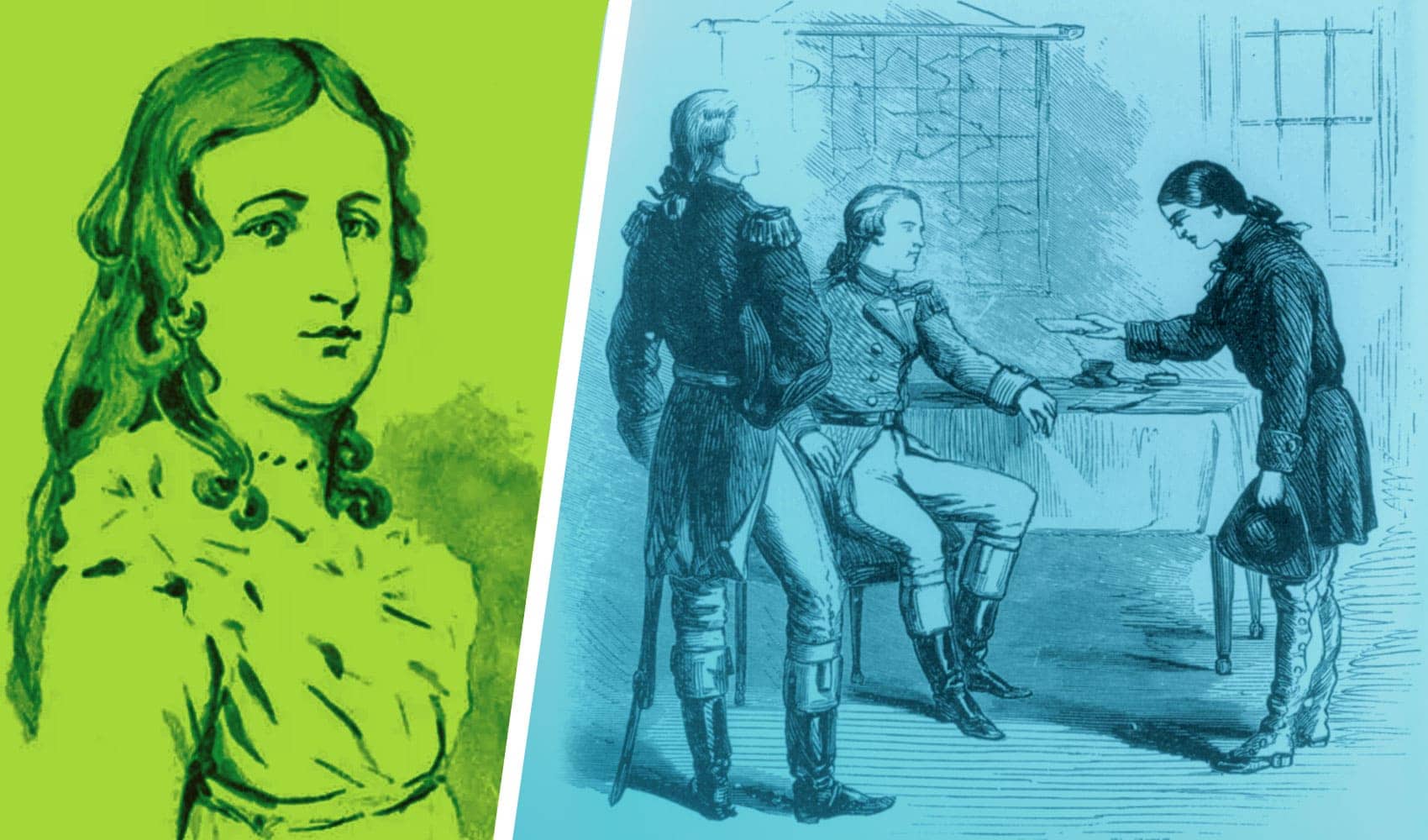

Deborah Sampson: “A faithful, gallant soldier”

What compelled Deborah Sampson to don men’s clothing and take up arms against the British? Perhaps prefiguring adventurous women like Sacagawea and Amelia Earhart, she simply wanted to break the mold.

Actually, she shattered it. Up to 1782, Sampson’s life had seemed humdrum. Born in Massachusetts in 1760, she was bound into indentured servitude at age 10. After completing her obligations eight years later, Sampson made ends meet by teaching and weaving. Then in 1782 she put on men’s clothing and journeyed to a town where she wouldn’t be recognized. There, claiming to be 17-year-old Robert Shurtleff (spellings vary), she enlisted in the Continental Army’s 4th Massachusetts Regiment.

Not long after, Sampson was sent to West Point, in the Hudson Highlands, as part of the Light Infantry Company of Captain George Webb. Like today’s Green Berets, Webb’s troops were given the most difficult and dangerous assignments — proof not only of Sampson’s courage and fortitude but the effectiveness of her cover-up. (“Her disguise may have been more likely to succeed having joined this company as no one would consider a female could keep up with the [rigorous] demands placed on such soldiers,” stated one historian.) Sampson’s comrades nicknamed her “Molly,” seeing that she grew no facial hair.

Sampson took part in missions patrolling the perilous “neutral country” in Westchester County. Located between British-held New York City and Patriot-controlled regions upstate, it was the scene of fierce partisan fighting. That summer, her moxie was put to the test when she took part in a skirmish near Tarrytown. During the combat, she received wounds from musket balls — one pierced her shoulder, another her thigh — as well as a gash on the head from a sword. Doctors treated Sampson’s head and removed the ball in her shoulder; she left the hospital before they could work on her thigh, which might have jeopardized her true identity. Accounts suggest Sampson either removed that ball herself or it remained in her body for the rest of her life.

Sampson couldn’t avoid detection in 1783, after she had been dispatched to Philadelphia to help stop a mutiny by Continental soldiers. There she caught a fever that put her close to a coma. According to a biography of Sampson published in 1797, “Thrusting his hand into my bosom to ascertain if there were motion at the heart, [the doctor] was surprised at finding an inner vest tightly compressing my breasts, the instant removal of which not only ascertained the fact of life, but disclosed the fact that I was a woman!” The doctor alerted Sampson’s superiors, who told General Washington. He ordered her honorable discharge on October 23, 1783, with back pay for her services.

Sampson returned to Massachusetts and a more traditional lifestyle that included marriage and three children. In testimonials seconding her application for a pension, members of the state legislature summed up her service perfectly, noting that Sampson “exhibited an extraordinary instance of female heroism by discharging the duties of a faithful, gallant soldier.”

Margaret Corbin: Keen-eyed “Captain Molly”

When push came to shove, Margaret Corbin pushed with a vengeance and earned a place in American military history.

During the Revolution, Corbin headed north from Pennsylvania with her soldier husband, serving as a camp follower. As fighting intensified during the 1776 Battle of Fort Washington in upper Manhattan, one of the Continental Army’s most disastrous defeats, she joined her husband in firing a cannon. When he was killed by a returning shot, Corbin kept right on firing until she was severely wounded and taken prisoner. Later, her colleagues on the line of artillery commended “Captain Molly” for her accuracy.

Upon Corbin’s release, she traveled to West Point and joined the Invalid Corps, composed of injured or physically compromised soldiers who were still eager to keep serving their new country, usually through guard duty. It is said that George Washington “took the Corps very seriously and was even proud of [those] who continued to fight after suffering such a tragedy.”

Corbin remained at West Point until the war’s end and stayed in the area afterward. She died in 1800, before reaching age 50, and now is buried in the cemetery at the U.S. Military Academy. The words on a plaque in Manhattan, not far from the site of Corbin’s heroic exploits, explains why she deserves to lie in this final resting place of countless generals. It honors her as “the first woman to take a soldier’s part in the War for Liberty.”

Sybil Ludington: “Simply too good not to be believed”

While some historians debate whether Sybil Ludington’s exploits actually occurred, in Putnam County and many American history textbooks her contributions to the war effort are accepted as fact. According to the story, the 16-year-old daughter of Col. Henry Ludington volunteered to rouse the militia led by her father so they could stop British troops on their way to destroy a major army supply depot in Danbury, Conn. Taking to her steed on the night of April 26, 1777 — a little over two years to the date of Paul Revere’s ride — she galloped from farm to farm, urging the men to assemble.

Although the exact route of Ludington’s ride is unknown, accounts suggest she rode at least 40 miles — twice the length of Revere’s alarm-calling adventure through the Boston suburbs. State historical markers across Putnam County (which at the time of the Revolution was part of Dutchess County) purport to trace her travels. The men eagerly responded to her call but arrived too late to prevent destruction of the military stores in Danbury. However, they helped inflict heavy casualties on the British as they retreated to their ships anchored on Long Island Sound.

Ludington, who later married and lived until 1839, never mentioned the ride. The first account of it appeared in a history of New York City published in 1880. Subsequent books added more details — that she wore her father’s clothes and rode through a driving rainstorm atop a horse named Star.

Over the years, Ludington has achieved fame that many Revolutionary War generals would envy. On the shore of Lake Gleneida in Carmel stands a statue of her crafted by renowned sculptor Anna Hyatt Huntington. Dedicated in 1961, it’s one of the most dramatic images of a participant in that or any conflict. Astride her charging steed, its mouth open and nostrils flaring, Ludington shouts at passing traffic, wielding a stick like a jockey’s crop. In 1975, at the time of the Revolution’s bicentennial, Ludington’s image graced a postage stamp. And an opera based on her ride premiered in 1993.

But did the ride actually take place? At this point, even historian Paula Hunt, whose deep dive into Ludington’s life and legend strongly called into question its authenticity, admits that it doesn’t matter:

“In the end,” she wrote, “Sybil Ludington has embodied the possibilities — courage, individuality, loyalty — that Americans of different genders, generations and political persuasions have considered to be the highest aspirations for themselves and for their country. The story of a lone, teenage girl riding for freedom, it seems, is simply too good not to be believed.”

Reed Sparling is a staff writer and historian at Scenic Hudson. He is the former editor of Hudson Valley Magazine, and currently co-edits the Hudson River Valley Review, a scholarly journal published by the Hudson River Valley Institute at Marist College.