Storm King Mountain was a popular subject for Thomas Cole and other artists associated with the 19th-century Hudson River School of painting. They would have agreed with Yale art historian Vincent Scully, who during his 1966 testimony supporting Scenic Hudson’s foundational campaign to protect this Hudson Highlands landmark so eloquently described it as “a dome of living granite” representing “a primitive embodiment of the energies of the earth.”

But in the 20th century, depictions of Storm King (and landscape painting in general) fell out of favor with prominent artists. They were more interested in depicting urban life and, later, with the development of Abstract Expressionism, the inner emotional landscape.

That’s why it was such a welcome surprise to find one important 20th-century painter, Gifford Beal (1879-1956), who filled numerous canvases with scenes of the valley — including several eye-popping depictions of Storm King. Not surprising, Beal had strong ties to the region.

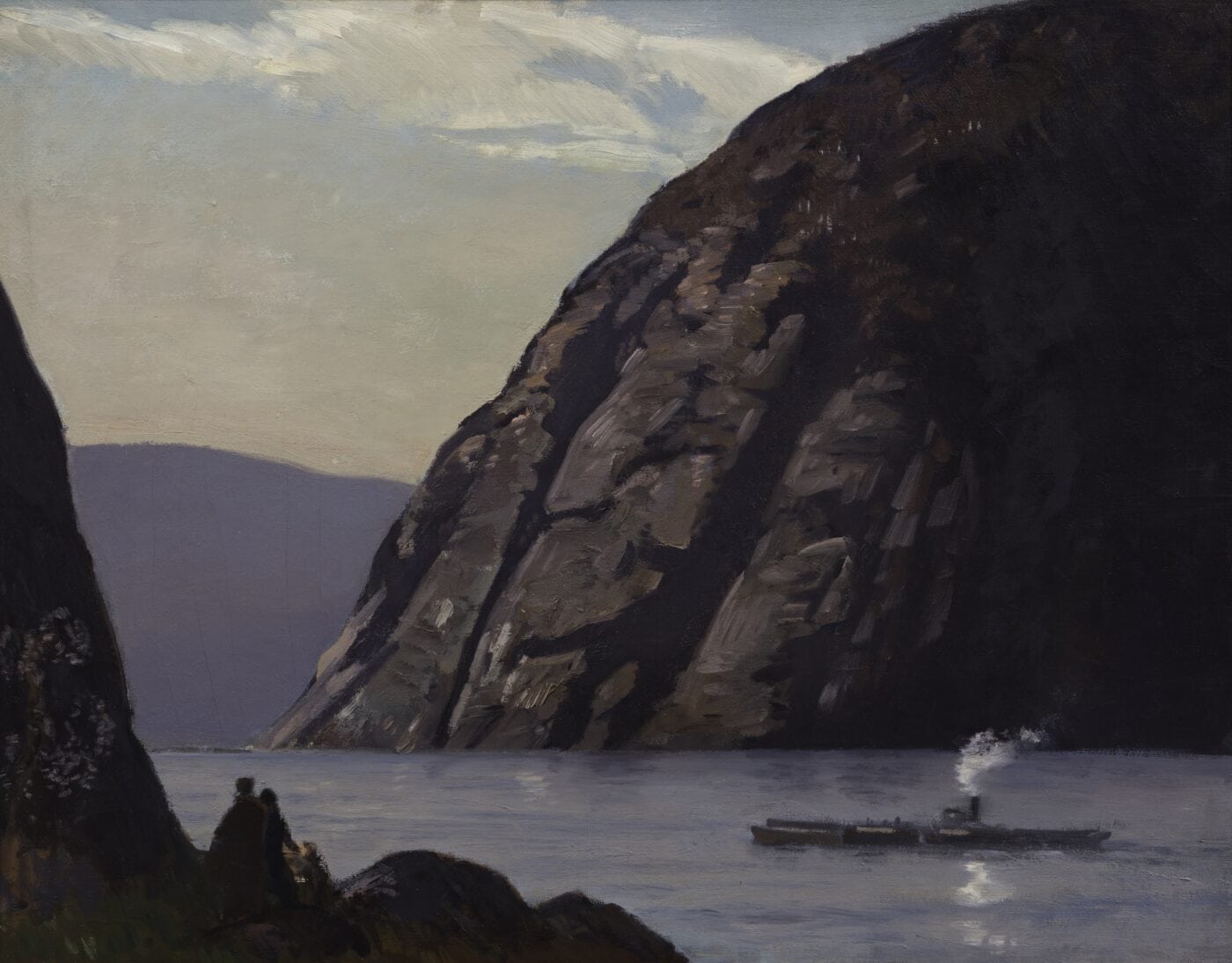

Beal’s bluntly titled “Storm King,” painted in 1914 and in the collection of the Hudson River Museum in Yonkers, might be the best painted equivalent of Scully’s words. The mountain practically bursts out of the canvas.

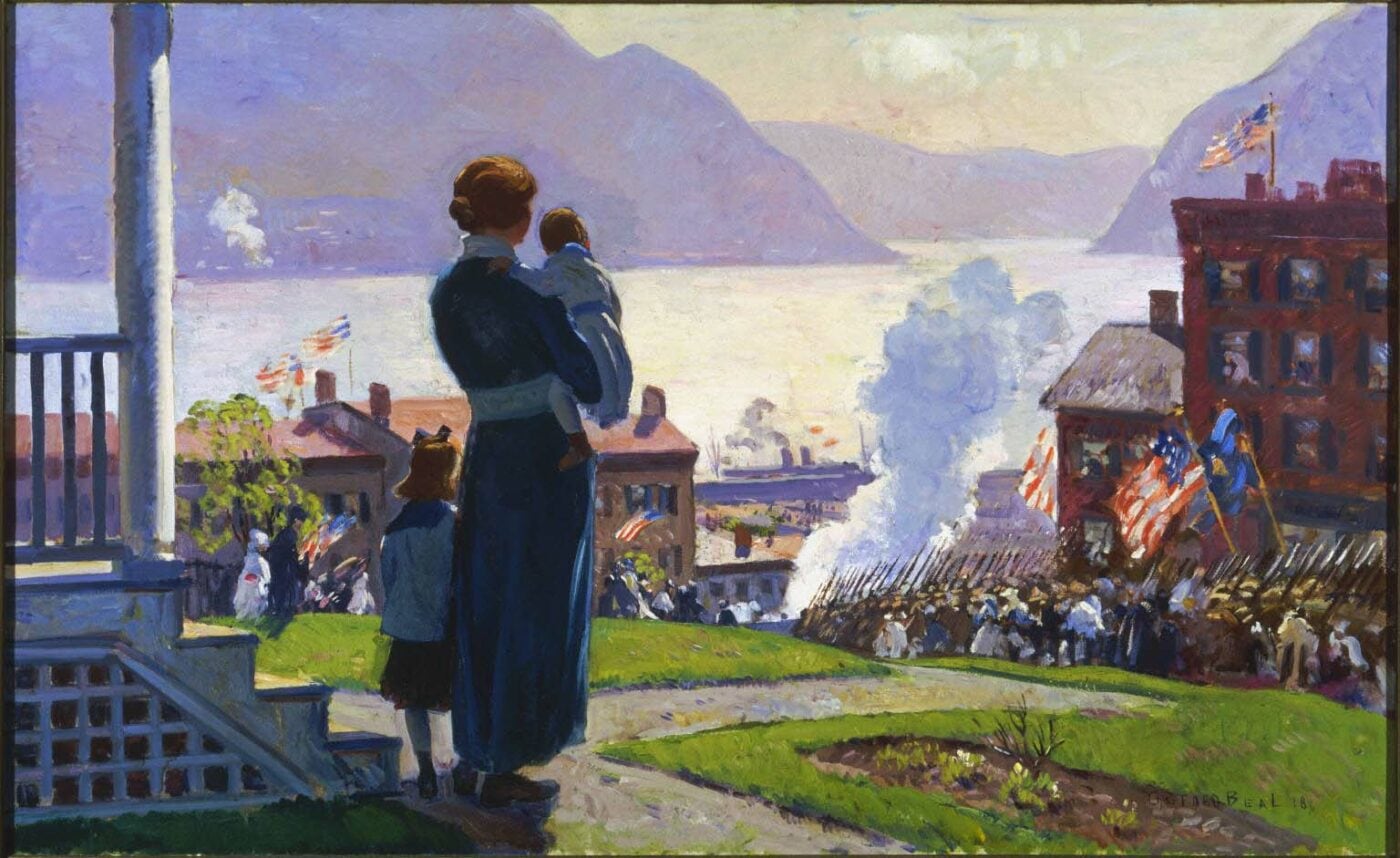

But an even more moving depiction is “On the Hudson at Newburgh.” Painted in 1918, it’s not strictly a landscape; its foreground features people saying goodbye to a company of soldiers destined for action in World War I. (“The whole city turned out to wave them off,” says City of Newburgh Historian Mary McTamaney, who researched the event.) But behind the marching soldiers and onlookers thronging a city street, Storm King (on the right) and Breakneck Ridge steal the viewer’s attention.

The backstory of the painting is just as eye-popping as its purple-hued background — because it was lost for 75 years, lying beneath a 1924 Beal canvas called “Parade of Elephants.” The cover-up was revealed in 1999, when restorers at Washington’s Phillips Collection, which owns the work(s), untacked a corner of the circus scene and revealed the painting below, as colorful as the day it was painted.

Why did Beal conceal “On the Hudson at Newburgh”? “Obviously, he didn’t care for it,” says Elizabeth Steele, head of conservation at the museum. “And he may have been out of stretchers.” Steele adds that while it’s “not a common practice” for artists to perform such cover-ups, “you wouldn’t be totally shocked.”

Beal’s affinity for the region can be traced to his parents, who owned an estate in the Balmville section of Newburgh. Their house, which still stands and is now owned by the Town of Newburgh, was dubbed “Willelyn,” a sort-of shorthand for the first names of its owners, William and Eleanor.

Along with his brother, Reynolds, also a painter, Gifford maintained a summertime studio on the top floor of the house. Its windows afford a magnificent view of the Hudson River and distant Highlands. Marjorie Phillips, a niece of the two artists (and co-creator with her husband, Duncan Phillips, of the Phillips Collection), later reminisced about the atmosphere in the studio: “Oh, the tubes of paint and the palettes. The canvases. The dedication to art,” she wrote.

From the house, Beal went on expeditions searching out subjects for his paintings. He became so renowned for his river scenes that contemporary critics considered him a worthy successor of the Hudson River School artists. “He was so talented. He had a really good eye for what was going on around him,” says McTamaney.

Beal’s father, perhaps his greatest artistic supporter, died in 1912, and his mother in 1921. Afterward, he traveled extensively. He rarely depicted the region again, focusing instead on genre scenes like “Parade of Elephants.” But he returned to the valley one final time — he’s buried in Newburgh’s Cedar Hill Cemetery.

Beal never attained “rock star” artistic status during his lifetime, although interest in his work was revived in the 1970s. Seeing Beal’s brilliant renderings of Storm King, even in reproduction, one can readily grasp his talent and appreciate all the more Scenic Hudson’s 17-year campaign to protect the “dome of living granite” that inspired him.