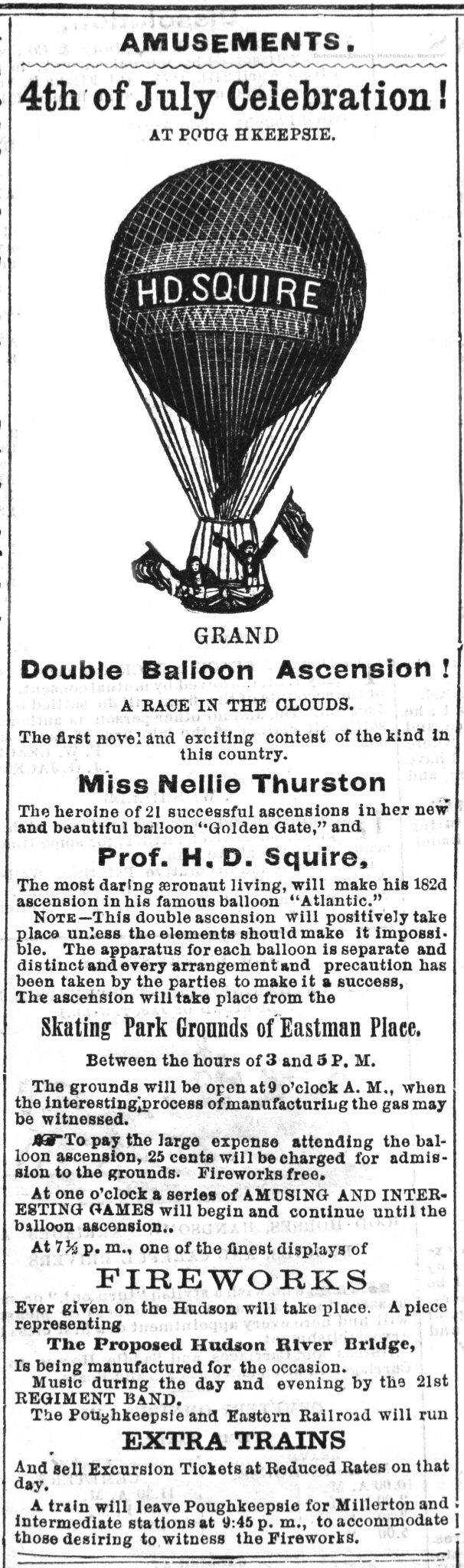

A race in the clouds on the Fourth of July, with one hot air balloon piloted by a woman! That’s what the Poughkeepsie Daily Eagle breathlessly promised readers in 1871 — putting the Hudson Valley at the center of a Victorian-era hot air ballooning craze that thrilled spectators on multiple continents.

The Fourth of July race heralded a landmark day in U.S. aeronautical history: the first twin balloon launch and, even more earthshaking, the first solo ascent by an American woman.

Not only did it take place in the Hudson Valley, but Nellie Thurston, the 25-year-old pilot of the Golden Gate, was born here as well.

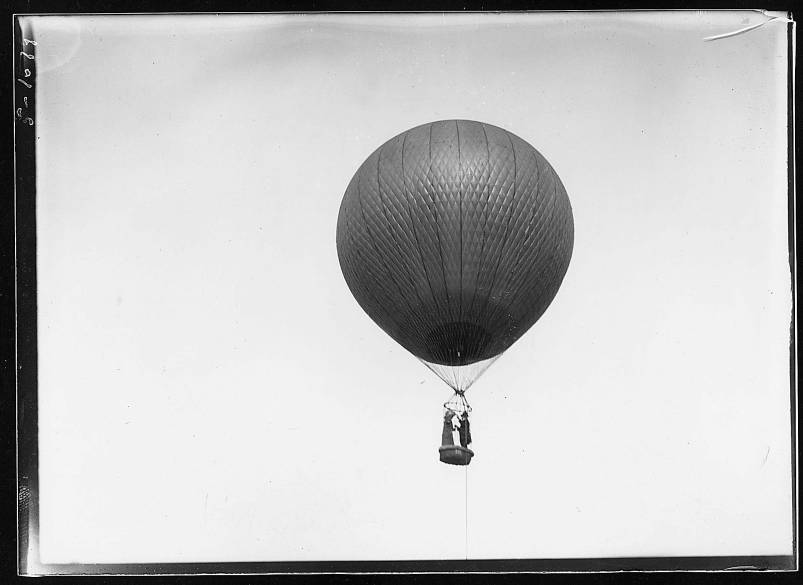

Before the Wright brothers, before aviation, the only way to take to the skies was nervy and unpredictable. Thurston was one of the first women to operate a hard-to-control balloon, soaring tens of thousands of feet in the air — without knowing where she would come down, or how she would be found.

Thurston’s daredevil flight that day put her in the stratosphere. She was estimated to reach a then-unheard-of altitude of more than 20,000 feet — nearly 4 miles in the air — not to mention the heights of national fame.

For nearly two decades, she would be revered as America’s most famous female daredevil, thrilling crowds in the Northeast, Midwest, and Canada on more than 100 subsequent solo flights.

It turns out Nellie Thurston was a stage name taken by Ellen Moss. Moss was born in 1846 in the Rensselaer County village of Lansingburgh (now part of Troy). She was no ballooning newbie when she took to the skies over Poughkeepsie, having made 21 previous ascents, the first (according to some accounts) at age 8. But on all of those flights she had been accompanied by a man — first her distant cousin, the pioneering balloonist John LaMountain and then Herman Squire, also a LaMountain protégé. (Thurston also was married to both men — LaMountain from 1864-66, and Squire for more than 50 years.)

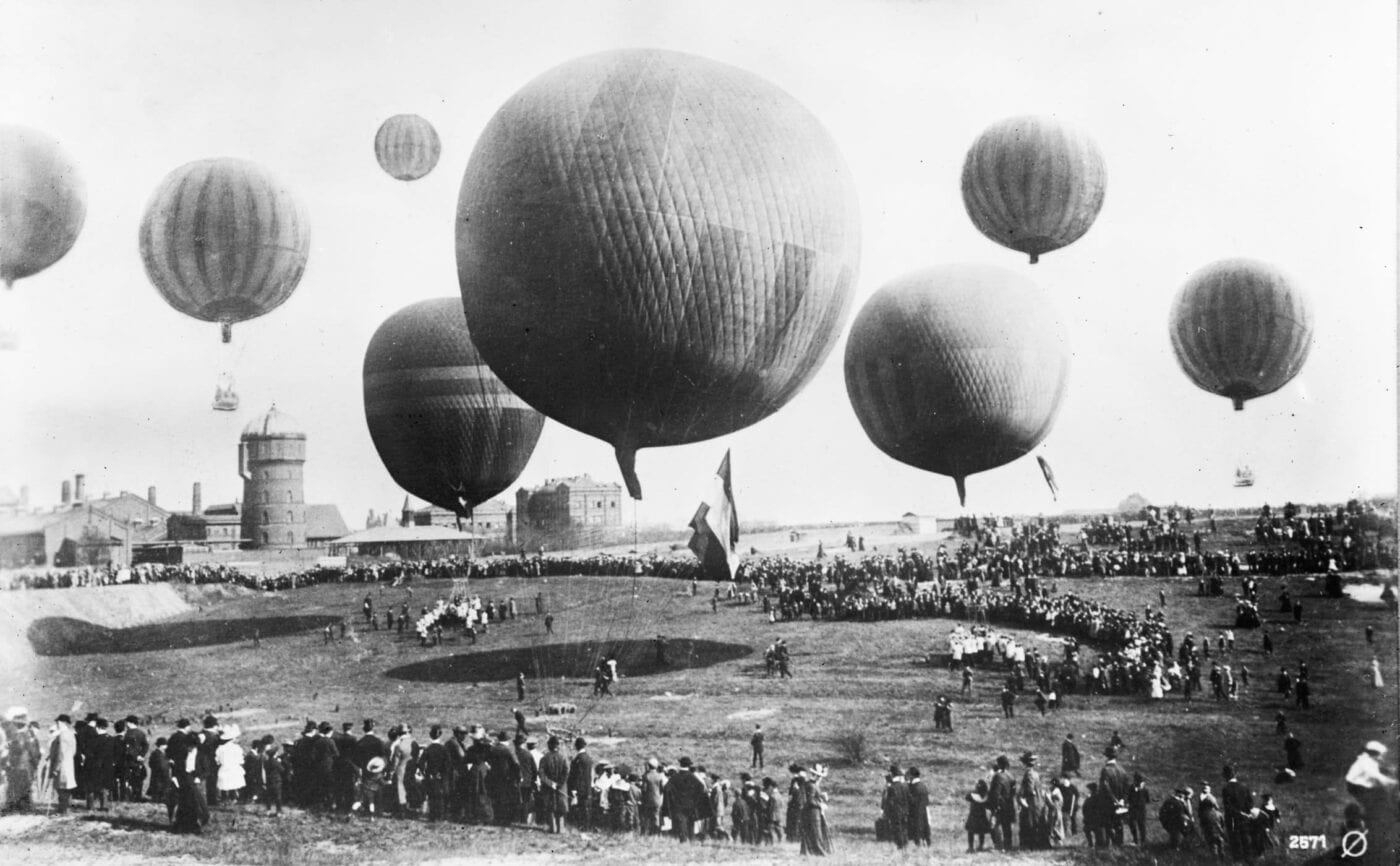

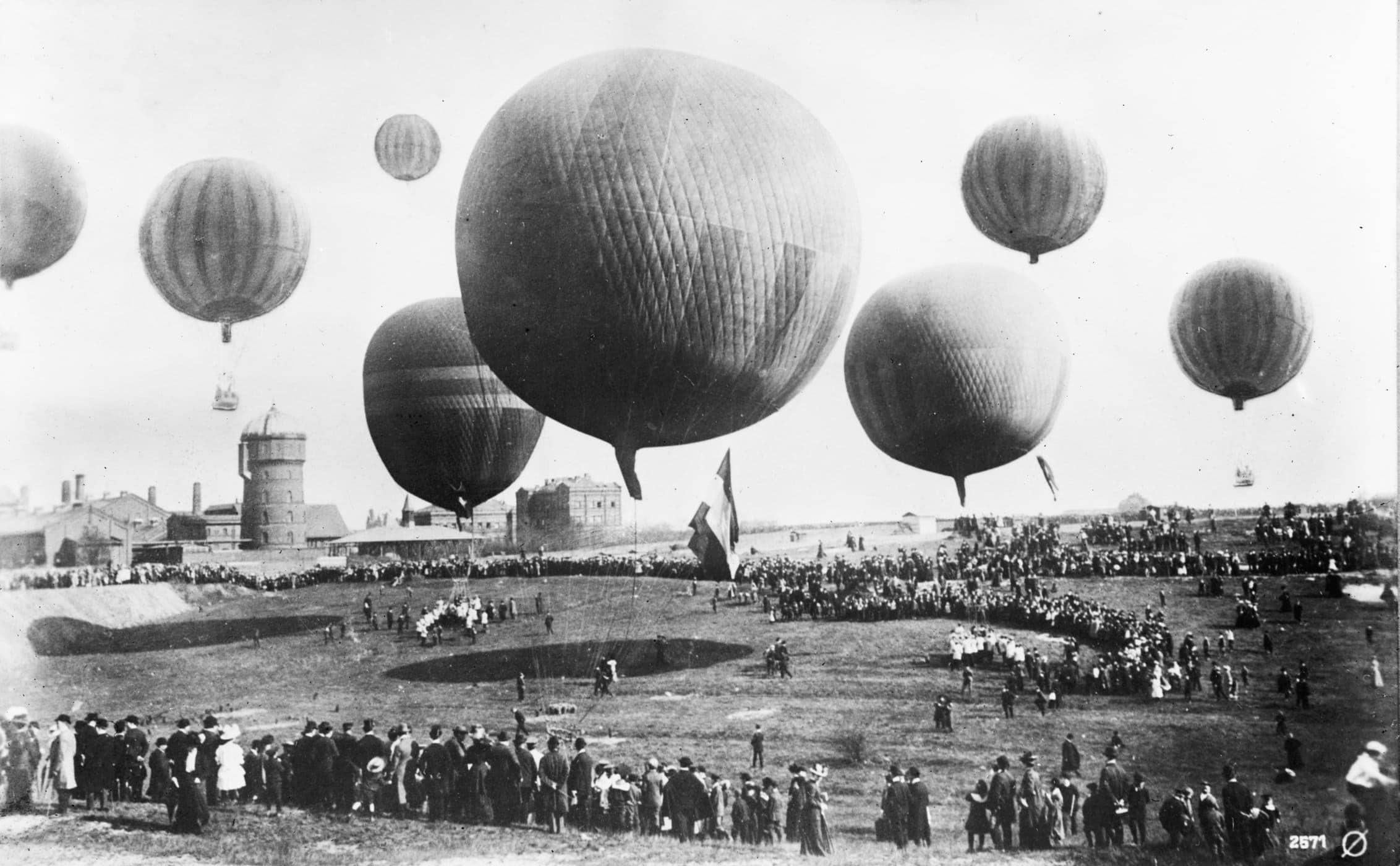

The massive Fourth of July contest and exposition drew more than 10,000 spectators to Poughkeepsie. Most of those who came to Eastman Park that day arrived early to witness the fascinating — and highly dangerous — spectacle of filling the fabric balloons, which took several hours.

Balloon races were thrilling events of the day, regularly drawing tens of thousands of spectators everywhere from Berlin to London, St. Louis to Indiana. The Victorian and later Edwardian crowds attended the festivities impeccably dressed in the full suits, elaborate dresses, and stylish hats.

Unlike today’s larger, tear-shaped balloons, which are inflated with hot air, the spherical craft back then were filled with flammable hydrogen, obtained by soaking iron filings in sulfuric acid and filtering the resulting gas through a layer of crushed limestone.

At 5 p.m., when the Atlantic and Golden Gate were filled and ready for takeoff, “All eyes were centered upon the lady,” noted the Poughkeepsie Daily Eagle. Describing Thurston as “small in stature” and “prepossessing in appearance,” it went on to note that she “was attired in a light suit, jaunty jockey and wore blue kids [gloves], dressed as though for an afternoon.”

The following day, Thurston provided the paper with this account of her history-making flight:

After I started I thought I would not ascend very high at first, as I wished to have a good view of your beautiful city. I floated along leisurely till I was satisfied, when I concluded to leave for the clouds and commenced to throw out ballast [bags filled with sand].

Mr. Squire (interrupting) Well, but what made you throw out so much sand?

Miss Thurston — Why, I saw you going for the clouds and I didn’t want you to get ahead of me; I didn’t want you to beat me.

[In subsequent remarks to reporters, Squire had this to say about Thurston’s rapid ascent: “I thought she was crazy. I was afraid her balloon would burst, and I think it would had it been an old one.”]

As soon as my balloon was relieved of so much ballast my flight upwards was very rapid; I should think at the rate of forty miles an hour. I went through three distinct rows of clouds, and then emerged into glorious sunlight. Above me was the clear blue sky, while below rested huge billows of white silvery linings presenting a splendid, dazzling aspect.

Commencing to grow dizzy, and a feeling of drowsiness coming over me, I resolved to go no higher. Winding the valve rope around my body I threw my weight upon it, pulling the valve open, and came down rapidly, hoping to catch a glimpse of Mr. Squire. Not seeing him after getting below the clouds I went up again, and was once more disappointed. Then I gave it up and looked about for a landing place.

Soon after I saw him coming down [Squire landed across the river south of Kingston] and then felt satisfied. I alighted in a lot between Staatsburg and Rhinebeck, on the east shore. Seeing the clearing I made all preparations for striking it.

[Interviewed prior to takeoff, Thurston said pulling the valve to descend was the hardest part of the journey: “[It] takes all my strength. I have to wind the rope about my waist and throw my whole weight on the cord…[but] never fear, I’ll manage it.”]

My balloon bounded along before the high wind, striking the ground three times, and going up again as many, until finally it struck against a stone wall, the basket on one side and the balloon on the other. For fifteen minutes I worked hard to anchor safely.

Just then a dog came long and I thought a man must be close by, and I was not disappointed, as a Celtic head peered over the side of the basket in which I was curled up, and exclaimed, ‘Are you there me darlint?” The exclamation came out so pat that I could not help but laughing loudly.

Saving my balloon beyond any doubt I alighted, and was escorted to Mr. DeGroff’s house and then driven to Staatsburgh, where I arrived too late for the train, and remained all night. It was a beautiful trip throughout.

Although other female balloonists would challenge Thurston’s airborne supremacy, none exceeded her fame, which continued to increase until her retirement from the sport in the late 1880s. After that, she lived quietly in Prospect, a small village in central New York, until her death at age 85 in 1932 — coincidentally the year Amelia Earhart became the first woman to fly solo across the Atlantic Ocean.