Thousands are expected to line the streets of Pearl River, N.Y., this year to watch the 62nd annual Rockland County St. Patrick’s Day Parade — one of the biggest parades of green in the nation. It’s no surprise that so many people in the county are eager to get their emerald on; Pearl River has one of the largest Irish populations in the state.

But many parts of the Hudson Valley have been shaped — culturally, economically and beyond — by the influx of Irish immigrants who settled here, especially starting in the 19th century.

One of the earliest recorded histories of the Irish in the Hudson Valley surrounds “Thomas, the Irishman” who, in court records dating to October 17, 1662, was involved in a dispute over ownership of a “barque” and was ordered to pay the other party “the equivalent of five beavers.” Apparently, Thomas Lewis owned land in what is now Marlboro in Ulster County, and frequently traded with Indigenous peoples. Around the same time, Irish settlers sailed up what is now the Hudson River from New Amsterdam (New York City) and started moving into Fort Orange, present-day Albany.

Many new Irish Americans immediately dedicated themselves to their adopted homeland. In 1779, General Anthony Wayne and Colonel Richard Butler, who had both emigrated from Ireland, fought at the Battle of Stony Point, which was an overwhelming victory for the Americans and the last major battle in the northern colonies. After the Revolution, Rockland County’s first judge, John Suffern, founded the town that now bears his name, although he had originally named it New Antrim after his birthplace in County Antrim, Ireland.

The church was long the center of Irish life in America. “People lived in small houses. It was difficult to have people over to your home, but the church was a way they could socialize,” said Elizabeth Stack, the former director of the Irish American Heritage Museum in Albany. St. Mary’s, the first Catholic church in upstate New York, opened in Albany in 1796 after a group of Irish residents petitioned the Vatican. It was the second parish in the state, following St. Peter’s, established several years earlier in what is now lower Manhattan. By 1807, parishioners of St. Mary’s numbered more than 300, although Catholics made up only one-twentieth of Albany’s population. Although a few older Catholic families were prosperous, most of the congregation was composed of poorer Irish immigrants.

Irish immigration to the Hudson Valley picked up steam in the early 1800s and continued through the “Great Famine,” which struck Ireland from 1845 to 1852 when the potato crop — the main source of sustenance — became infected, and the island nation suffered a period of extreme disease and starvation. The “potato blight” left a million dead, and another million fled the country. In the 1840s half of all immigrants coming to the U.S. were Irish.

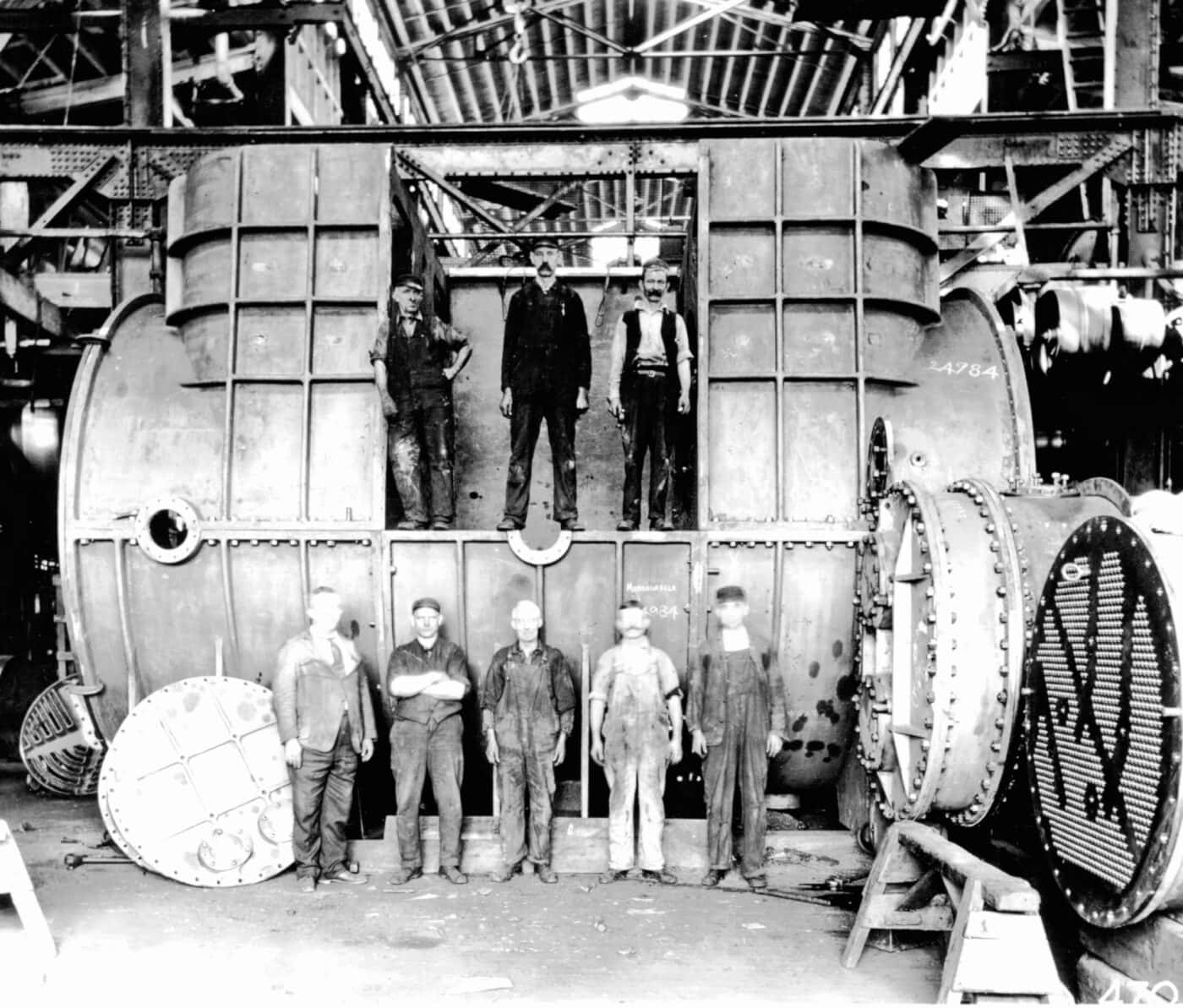

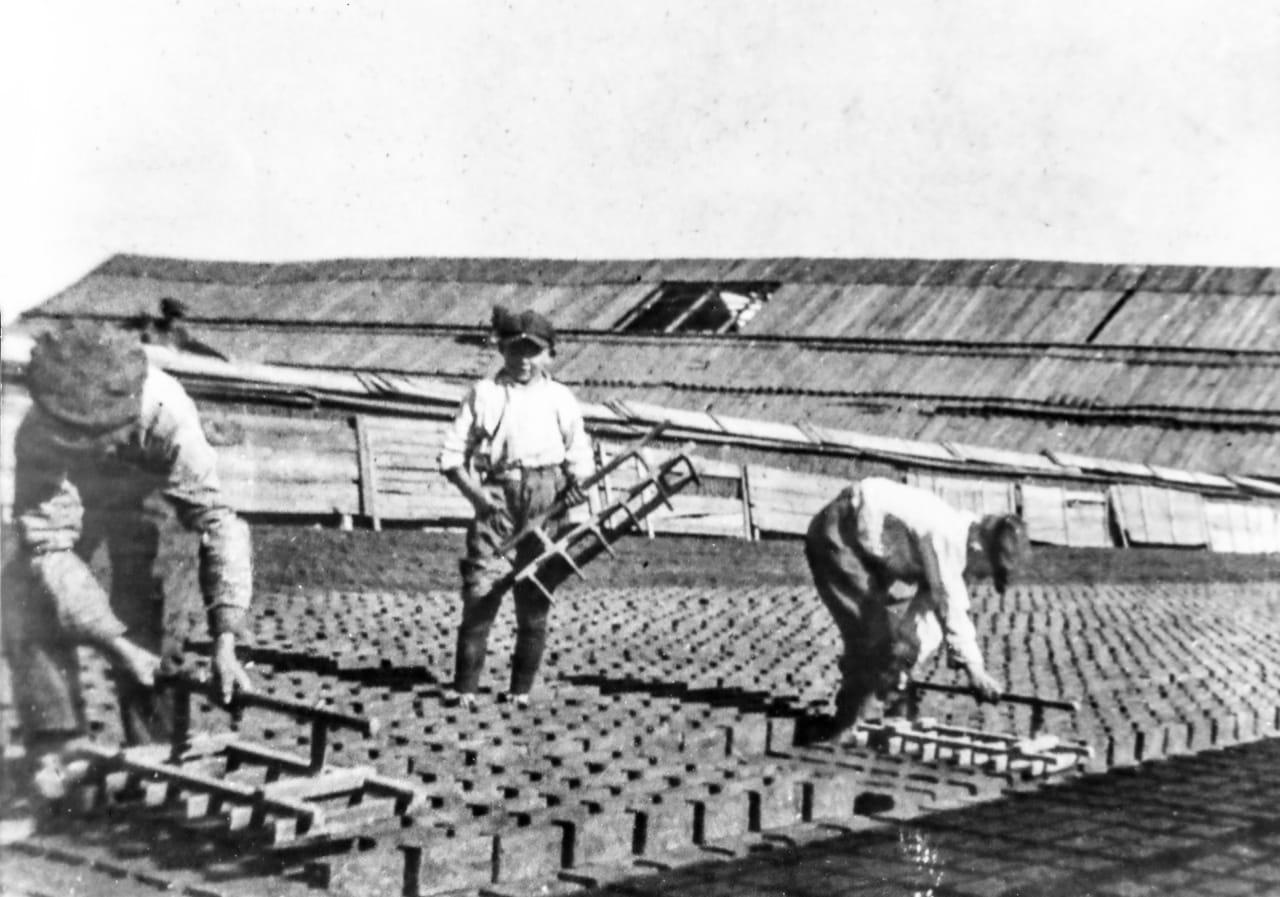

Luckily, several booming industries in the Hudson Valley provided a soft landing spot for the refugees. The Hudson River brick industry began in 1771 when Dutch settler Jacob Van Dyke discovered huge deposits of clay in the Hudson River and began making bricks by hand in Haverstraw. A century later, Haverstraw would be the undisputed brick-making capital of the world; at one time, about two-thirds of the buildings in New York City were built with Haverstraw bricks. In 1883, the bustling town had 42 brickyards — and at least 10 of them had Irish owners.

In the 1840s, Irish immigrants were the first to come en masse to work in the brick factories. “Entire families worked in the brickyards,” says Rachel Whitlow, executive director of the Haverstraw Brick Museum. “Kids started as young as 8 years old ‘spatting’ the bricks — basically knocking off the excess clay so they would be ready for the kiln. By the time they were 18, they had learned every bit of the brick industry. Women worked here too, but were paid less.”

The Malley Brickyard, started by Irish brothers Will and Tom, was one of the first and most successful in the region. After several years they added another brickyard up river in Fishkill. “It was one of the first integrated brickyards. In general, the Irish-owned brickyards tended to be the most diverse and welcoming of other ethnicities. The brickyards owned by the Italians and the Polish tended to employ their own,” Whitlow says. “But while everyone worked well together, when they left the brickyards it was a different story. Everyone was very segregated. The Irish on one block, the Italians on another. They even had their own fire departments.”

The Rockland County Ancient Order of Hibernians organized in Haverstraw in 1882. There were no parades at that time, but newspaper clips mention Hibernian picnics, where tens of thousands gathered in a local park to enjoy Irish dancing and singing competitions. (Today, the annual Rockland County Feis continues this tradition.)

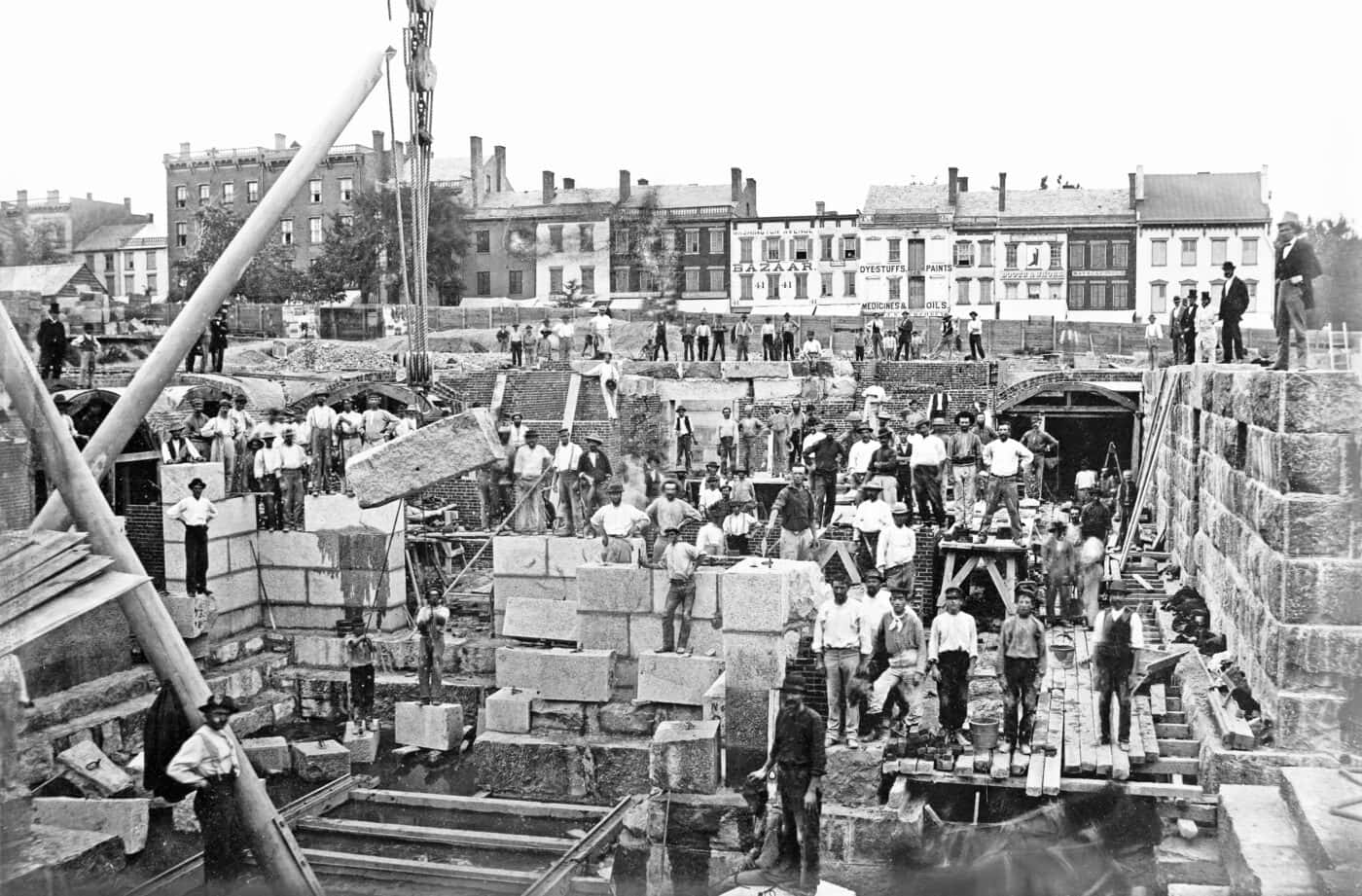

Irish immigrants also flocked to the business of building canals. The Erie Canal, an unprecedented engineering marvel, stretched 360 miles from the Hudson River to the Great Lakes when it opened in 1825. It was built over the previous eight years by raw hands — including those of many Irish laborers.

The 108-mile Delaware & Hudson (D&H) Canal broke ground in 1825 and opened just three years later. Its impact on the Hudson Valley was monumental, making Kingston the busiest port between New York City and Albany. Once again, few locals would work for the low wages that the newly arrived Irish would. In the book Canal Days in America, Harry Drago wrote: “As usual, the labor contractors brought in hordes of immigrant Irish and several hundred Germans as well. The Irish fought the Germans … The German laborers and the ‘wild Irish’ could not be housed together.”

Like the brick factories, the D&H Canal provided hardworking Irish immigrants the opportunity to slowly move up in the world. Take the story of John Murray. Born in Ireland around 1824, he came to New York at 14 or 15, and immediately began working for a boat captain hauling coal for the D&H Canal Company. He was illiterate and first worked as a driver or “hoggee,” walking the towpath to guide the mule, for five dollars a month. The next season he worked as a bowman, assisting onboard for eight dollars monthly. From 1853-1856, he was captain on a “full river boat” for the Pennsylvania Coal Company, running coal up the canal from Waymart, Penn., to Rondout, N.Y., and then down the Hudson to NYC. Murray’s progress through the ranks was typical; boys started working on the canal as young as seven years old, some making captain by 14.

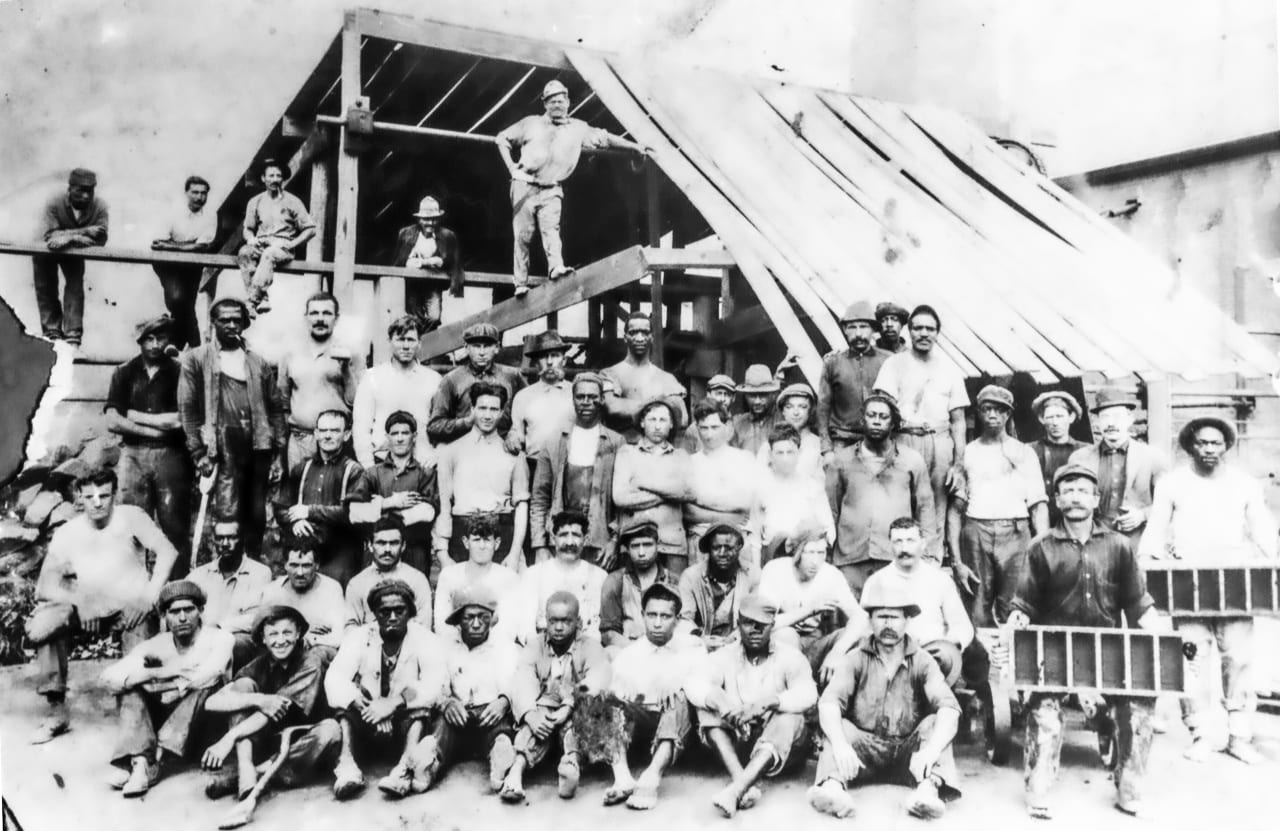

In the early 1900s, Irish immigration in the U.S. slowed considerably, due to the fact that Ireland’s economic situation had recovered somewhat, but also because the Emergency Immigration Acts of 1921 and 1924 reduced the numbers of all immigrants coming into the country. Still, Irish immigrants in these years often became construction laborers, helping to build New York City, Boston, and Chicago in particular. As U2 sings in the band’s popular song: “These are the hands that built America.”