When West Point Foundry Preserve reopened in 2013, after a 16-month construction project and years of planning, the new “historical park” became an instant hit, both with the public and landscape architects.

In addition to earning a cover story in Landscape Architecture Magazine — pretty much like winning an Oscar in the field — it was one of the nation’s first natural areas certified by the Sustainable Sites Initiative, recognizing its positive environmental impact. Leading the planning and design of the “new” preserve was Kim Mathews, a founding partner of Mathews Nielsen Landscape Architects (MNLA).

A native of Florida’s Pandhandle and a fellow of the American Society of Landscape Architects, Mathews earned a BFA in painting from the University of North Carolina and a master’s in landscape architecture from the University of Pennsylvania. During her 35-year career, she combined her skills in “reading the landscape” with an interest in storytelling to design some of the firm’s signature projects — among which West Point Foundry Preserve is her favorite. Though retired from MNLA, she does pro bono work creating parks in communities of need and has resumed painting landscapes, which she put on hold during her career.

What do you remember creating as a child?

A lot of my childhood revolved around the upkeep of our family’s wooden sailboat, so I learned about painting, sanding, scraping and woodworking at an early age. My mom taught me how to sew, the whole process of making patterns and detailing. I think I got my creative side from her. When I was a kid, we also loved to build these whole villages in our backyard, making houses and farm fields and rivers and roads and bridges out of sticks and stones and pine bark. That was probably my early adventure as a budding landscape architect.

Any favorite outdoor experiences?

I grew up in North Florida, which has a karst topography — a limestone landscape, lots of sinkholes. There was this place, which we called in our childhood language the Big Ditch. It was this mysterious, wonderful place. We’d stand at the rim and look down into it — and whole trees grew up inside of it. I realized later on it was kind of like the ravine of West Point Foundry Preserve.

You got your bachelor’s degree in painting. How did that translate into landscape architecture?

I’d never even heard of a landscape architect until I was, I think, 26. I moved from the South to the North thinking I wanted to be an architect, and I soon realized that’s not what I wanted. In the process, I met a landscape architect, and I thought his profession sounded wonderful. I think my background in painting is what helped me learn to see a landscape. It certainly helped me in graduate school, to build a portfolio and visualize projects.

What prepared you for designing West Point Foundry Preserve?

I had just finished up in Buffalo at the historic terminus of the Erie Canal. At that site, we unearthed the canal, the towpaths, the building foundations around it. And we worked with a team of archaeologists and engineers and exhibit designers, and it was the same kind of process from master plan to design to construction.

In Buffalo, I also learned the importance of authenticity when you’re doing a preservation project. I don’t mean that you have to reconstruct something to look like it did then, because first off, you can hardly ever do that, and it’s usually too expensive. But people want to feel like they’re in the exact spot where this thing was or this person stood, and they really want to be able to immerse themselves in that history.

What were your first impression of the West Point Foundry site?

First off, I was most taken by the natural framework: the ravine, the sound of water, the relationship to the river, the cove. It kind of blew me away. But then I think the thing that was really of interest to me is the fact that we had to tease the story out of this site and figure out a way to leave it more or less intact as a functioning ecosystem, but still allow people to get in there and see and discover and touch the places that the site represented.

It wasn’t until I got into the project that I realized the significance of the industrial archeology and the foundry’s importance — locally, nationally, even internationally. And then I became a bit of a foundry nerd; I would go to any site I could. On vacations, I would drag my husband.

Was public input an important part of the way it finally came out?

What I learned from the public process is that the people and the Village of Cold Spring cared so much about the site, and it became for me almost a personal commitment to do it the right way. At the grand opening, this gentleman who lived in the village shook my hand and said, “Thank you. You didn’t screw it up.” He was really glad that I hadn’t made it something it wasn’t. I took that as a high compliment.

Did the research by Michigan Technological University’s Industrial Archaeology program help?

Absolutely. When we started this project, we were really overloaded with information. We had it coming from all directions — all the different ecological habitats, the edge of the Superfund site, the archeological areas, things that had been uncovered, things that hadn’t been uncovered, the soils issues. And in the end, we realized the most important framework was to map out the areas that Michigan Tech had already investigated and covered over. If we needed to disturb an area or build something across it, or over it, we could do it there because that had already been properly documented.

I remember when they were in the middle of constructing the foundations for the stairs next to the water wheel. The footings were placed within an inch of every historic element — we had to get them in carefully so we wouldn’t disturb anything. And then I got this phone call from the contractor, who said, “Oh my God, we just dug the hole and there’s a privy there.” If you know anything about archaeology, privies are like gold mines because people used to throw stuff down them. So everything had to stop and be investigated. Finally, we had to move one of the footings a little bit.

Do you have a favorite part of the preserve?

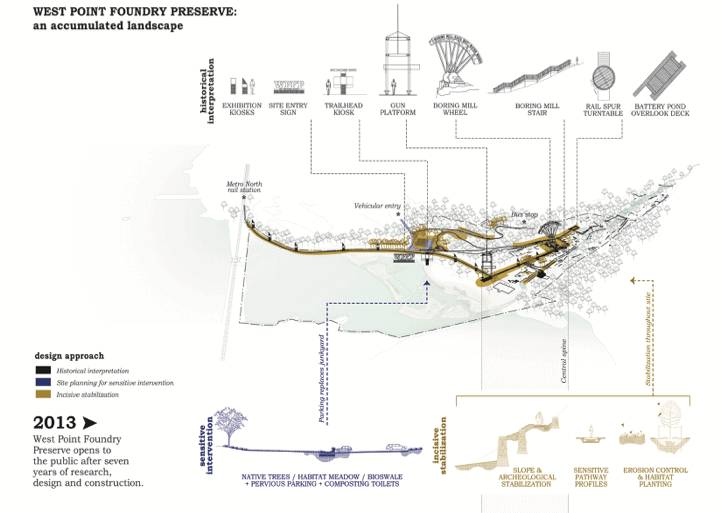

I really love the central spine, and the fact that it reveals the site in all seasons. You can look down to the cove in the fog. You can be there when all the trees are turning brilliant yellow in the fall. You can be there in the spring and hear the brook. It sort of stitches the whole thing together.

What would you say was the biggest design challenge?

Access. As a site planner and designer, circulation is the most important thing. If you don’t get that right, then it’s hard to recover because you’ve laid it down. I was very cognizant of the fact that I was the first designer to touch this site, and probably the last for a long time, and I wanted to really make sure that the circulation respected the very complicated features. We had archeological protection zones, we had wetlands, we had other environmentally sensitive sites. We had to really thread everything in.