From the beginning, stargazing has been part of the curriculum at Poughkeepsie’s Vassar College. That’s because Maria Mitchell — America’s first female professional astronomer — was one of nine instructors selected to join the school’s founding faculty in 1865.

Along with her expertise in exploring the heavens, Mitchell brought teaching methods to Vassar that broke conventions of the time. Her demand that students engage in firsthand observation and research has been an essential and invaluable aspect of learning at the college ever since.

“Maria’s legacy fills the campus,” says Debra Elmegreen, who just retired as chair of Vassar’s Department of Physics and Astronomy. Signaling Mitchell’s continued presence, Elmegreen’s post as professor of astronomy was named after her pioneering predecessor.

Spotting a comet leads to fame

Mitchell was born in 1818 on the island of Nantucket, where she picked up her interest in otherworldly exploration from her father. William Mitchell was an accomplished amateur astronomer who positioned a telescope on top of the bank where he was employed. After working days as librarian of the Nantucket Atheneum, young Maria Mitchell would climb to the rooftop observatory and join him in scanning the night sky.

In October 1847, peering through the lens paid off when Mitchell spied a blurry streak. After repeated observations, she announced her find: a comet. She became first American scientist to discover one of these extraterrestrial bodies, subsequently named “Miss Mitchell’s comet.”

The accolades came rushing in. She was awarded a gold medal by King Frederick VI of Denmark. The following year, she became the first woman elected to the American Academy of Arts and Sciences.

Shy by nature, Mitchell was startled by the sudden acclaim. “It is really amusing to find one’s self lionized … to see the doors of fashionable mansions open wide to receive you, which never opened before,” she wrote in her diary. “One does enjoy acting the part of greatness for a while [but] I was tired after three days of it.”

A “new era of learning”

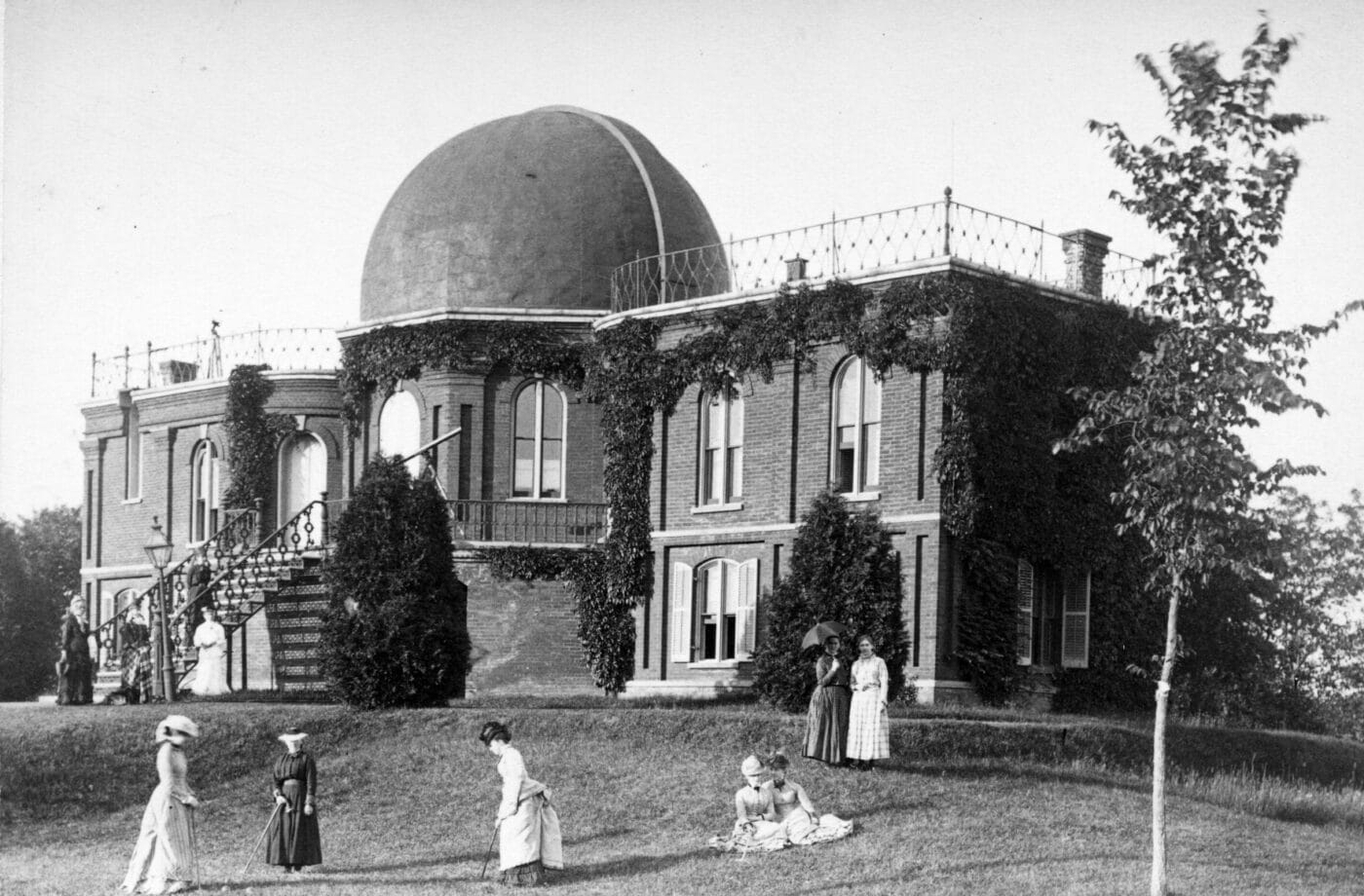

Mitchell’s arrival at Vassar coincided with construction of the college’s first building, an observatory that would serve as her workplace, classroom, and residence for the next 23 years. Through the building’s 12-inch telescope, then one of the country’s largest, she continued making important observations — of sunspots, nebulae, stars, and the moons of Saturn and Jupiter.

In 1963, the telescope was donated to the Smithsonian. Elmegreen, then only 12 years old but already already determined to become an astronomer, still recalls the excitement of seeing it on display there.

Mitchell also developed a technique for photographing the sun. These groundbreaking plates remained in an observatory closet until their “rediscovery” during a housecleaning in 1997.

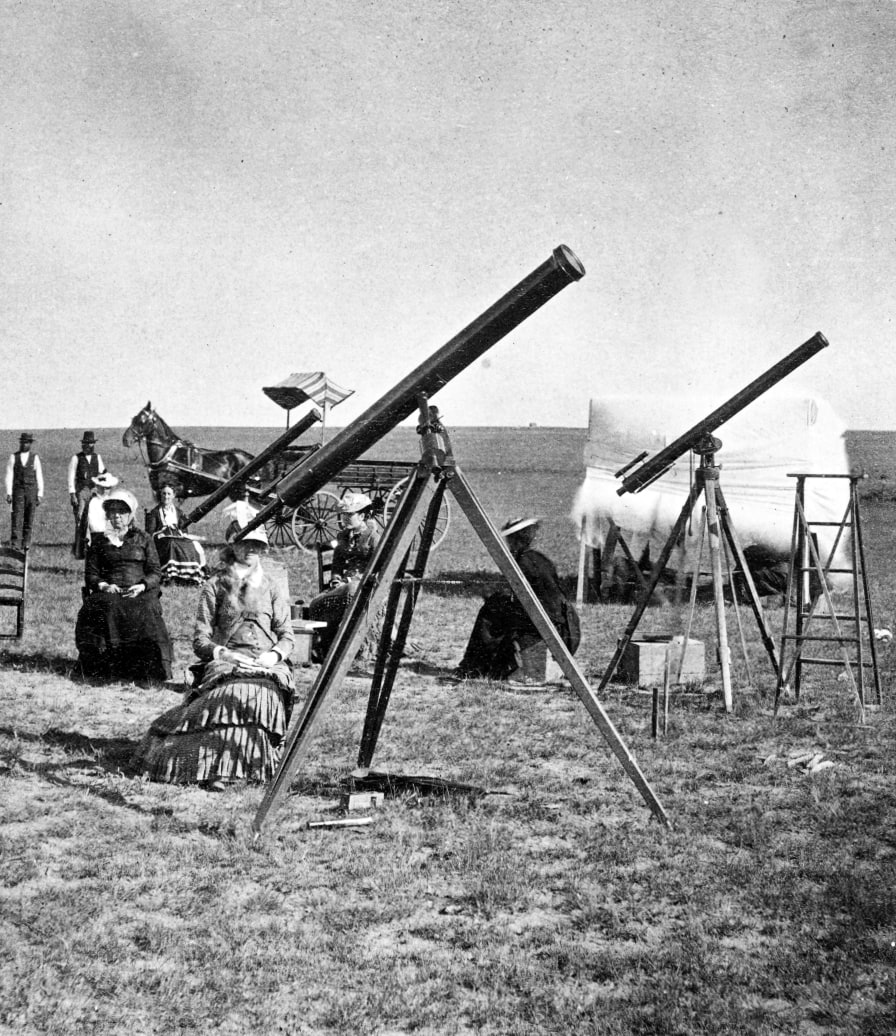

But Mitchell’s most significant contribution at Vassar may have been the way she taught and inspired her students at the then all-female school. At a time when women were expected to be in their beds at night, she demanded their presence at the observatory during these optimum hours to conduct research. She also led them in cross-country expeditions to enhance their observations, to Iowa in 1869 and Colorado in 1878 to watch eclipses.

“When I went to Kansas City for the 2017 solar eclipse, I thought with admiration about Maria’s two eclipse trips, traveling by train across the country with her young female students and her equipment,” says Elmegreen. “She was the only woman scientist on those expeditions.” Indeed, as noted by Vassar’s online encyclopedia, “At a time when men’s colleges seldom engaged science students with direct field experience of this kind, [Mitchell’s] students were entering the new era of learning for women.”

Mitchell’s methods have remained a hallmark at the college. “Throughout my 37 years at Vassar, I have been guided by Maria’s method of wanting students to learn by observing, not just by reading something in a book,” says Elmegreen. “I’ve incorporated hands-on exercises in the classroom, as well as engaging students in summer research projects. Now they also reduce data from the Hubble Space Telescope and other national observatories through remote observing, or gather data at our Class of ’51 Observatory on campus. Either way, they learn to observe and analyze for themselves, just as Maria encouraged her students.”

A number of women who studied under Mitchell went on to prominent careers in astronomy, but her encouragement wasn’t confined to that field. She was outspoken in the women’s suffrage movement and in 1873 helped found the American Association for the Advancement of Women, created “to receive and present practical methods for securing to women higher intellectual, moral, and physical conditions, and thereby to improve all domestic and social relations.”

Imagination, beauty, and poetry

Elmegreen has been a astronomy pioneer in her own right — she was the first woman to graduate from Princeton with an undergraduate degree in astrophysics and the first female postdoctoral researcher to be a Carnegie Fellow. In her generation, she says women made up about 10% of the field. Today, the membership of the International Astronomical Union, of which she is president, is about 20% female. “The percentage is moving, but slowly still,” she admits.

For Elmegreen, as well as budding astronomers, Maria Mitchell remains an inspiration, both for her research methods and the amazement she felt — and shared — in connecting with worlds beyond our own. She quotes Mitchell as she says: “‘We especially need imagination in science. It is not all mathematics, nor all logic, but it is somewhat beauty and poetry.'”