Poets’ Walk Park remains one of the Hudson Valley’s most popular destinations for enjoying spectacular views of the Hudson River and Catskill Mountains — a place where landscape becomes poetry. Yet it turns out the story we’ve been telling about that landscape isn’t quite right. The park opened to the public on June 22, 1996, and its anniversary this month seems like a fitting moment to set the record straight.

For many years, the park’s “romantic” design was attributed to Hans Jacob Ehlers (1804-58), one of the pioneers of American landscape architecture. But writing history is often a process of making new discoveries as you go. That has been the case with Ehlers, whom we recently discovered isn’t really responsible for the park’s design at all.

“Ehlers had nothing to do with the pastoral look of those meadows, hedgerows, tree lines, and westerly views!” Wint Aldrich says emphatically. Aldrich should know: He is co-owner of the Rokeby estate north of the park and former deputy commissioner at the state Office of Parks, Recreation and Historic Preservation. His family has meticulously maintained historical records of the area going back to the 18th century.

“All the land remained pretty much as developed in the 18th century by tenant farmers,” Aldrich adds. “I know it would be wonderful to be able to say that Poets’ Walk Park reflects a master’s romantic landscape design, tying in with the literary lights of the era, but it simply would not be true.”

Correcting the record

So where did the story of Ehlers’ role in designing Poets’ Walk Park originate? Not clear. But perhaps it was assumed because much of his documented work took place around it.

A graduate of the Royal Danish Forestry School in his native Denmark, Ehlers immigrated to the U.S. in the 1840s. On the transatlantic passage, he met Samuel Ward, the son-in-law of William B. Astor. Astor owned Rokeby, whose lands included today’s Poets’ Walk Park. Ward realized that Ehlers would need employment. He also knew that the Astors were keen on horticultural improvements at Rokeby. So Ehlers and his young son Louis (who went on to have his own successful landscape design career in the Hudson Valley) wound up in Red Hook.

Rokeby has remained in the same family for 11 generations. Among the estate’s extensive historical collection are plans prepared by Ehlers for the estate’s front drive and landscaping around the house. Another set of plans for Steen Valetje, the 100-acre estate south of Poets’ Walk Park (located on land gifted by William B. Astor to his daughter and son-in-law Franklin Hughes Delano), reveal work Ehlers did around that house as well. But the land encompassing today’s park? No record exists to suggest Ehlers contributed anything to its overall design.

Aldrich admits that Ehlers could be responsible for one aspect of the park: its actual Poets’ Walk. “As to whether Ehlers had a hand in improving the old haul-way up from the river with bridge, summerhouse, etc., leading it to be named by the Astors in honor of Washington Irving and Fitz-Greene Halleck, we have no documentary proof, but it is certainly possible,” he says.

Inspired nature

Historic design pedigree or not, Poets’ Walk Park has what Andrew Jackson Downing, the “father” of American landscape architecture, called “spirited irregularity,” critical for generating excitement, emotion, and inspiration. (Incidentally, Downing did not hold Ehlers in high esteem; he criticized his work in an essay titled “Note on Professional Quackery.”)

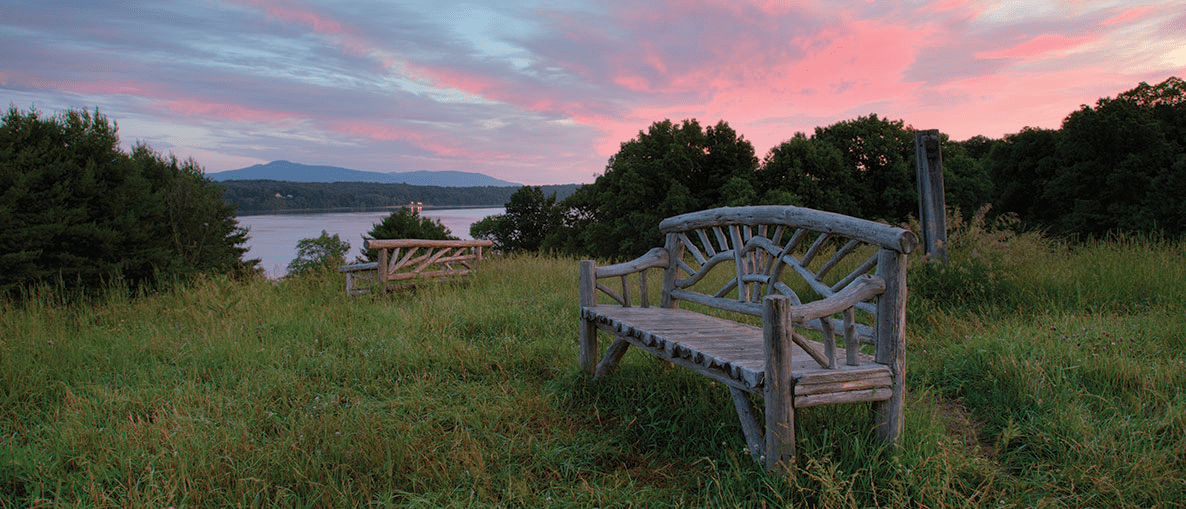

The park’s winding trails pass through a stunning procession of natural features — enveloping woods, wind-swept meadows, a shaded ravine, and at last the all-encompassing view of river and mountains. Its vistas contract and expand, and viewers’ perspectives change with nearly every footstep. Both increase suspense and mystery, a chief goal of romantic landscape design.

Ehlers, along with Downing, might be delighted to have their names associated with a place offering so much beauty and pleasure, a place that achieves their design ideals. Correcting the record is an inevitable part of the historic evaluation and reassessment process. And so it turns out the real story at Poets’ Walk Park is that nobody created this extraordinary romantic landscape. It simply created itself with an assist from some 18th-century farmers.

Poets’ Walk. (Past photo: Rokeby archives; present photo: Tyler Blodgett / Scenic Hudson)

The long-forgotten poet at Poets’ Walk

Of the two writers for whom Poets’ Walk is named, both visitors at Rokeby, Washington Irving has retained the renown he earned during his lifetime, while Fitz-Greene Halleck has dropped off the literary map. Halleck was once a literary rock star. He was hailed as the “American Byron,” admired by Charles Dickens, read aloud in the White House by Abraham Lincoln, and honored with a statue in Manhattan’s Central Park. At the same time, he served as private secretary to William B. Astor’s father, John Jacob.

Halleck penned dozens of poems, but who today can remember the name of one, let alone recite a few verses? There’s good reason for that. He tended to write in a turgid Victorian style (Edgar Allan Poe said reading one of his poems was “little less than torture”). But in this bright, evocative excerpt from “The World is Bright Before Thee,” Halleck succeeds in melding nature with poetry, exactly what attracts people to Poets’ Walk Park.

The world is bright before thee,

From “The World is Bright Before Thee,”

Its summer flowers are thine,

Its calm blue sky is o’er thee,

Thy bosom Pleasure’s shrine;

And thine the sunbeam given

To Nature’s morning hour,

Pure, warm, as when from heaven

It burst on Eden’s bower.

by Fitz-Greene Halleck