Of course, Christmas — one of many holiday traditions celebrated today in the Hudson Valley — didn’t originate here. But the region can take credit for turning it into the joyous social occasion that many people celebrate today, a holiday season famous on the streets of New York City and beyond. Plus, the valley helped introduce the world to Santa Claus.

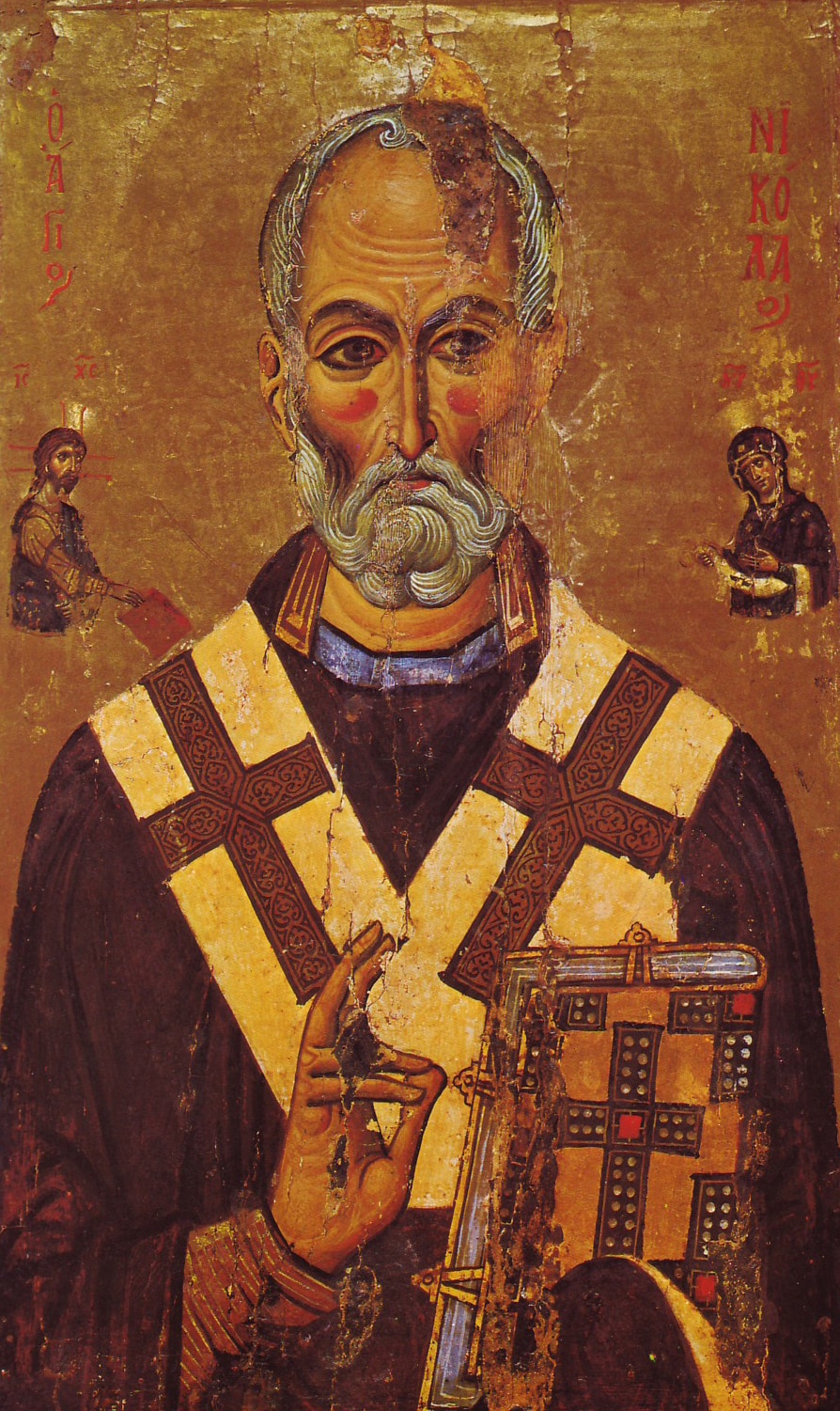

In the early 19th century, Christmas in the U.S. was a somber affair, if it was celebrated at all. St. Nicholas was portrayed with a dour, even severe demeanor.

“The country as a whole could not determine whether [Christmas] was to be considered sacred, secular or entirely blasphemous,” says author Andrew Burstein. As a result, he continues, “Observation was irregular at best.” Some places actually banned holiday festivities because of the potential for drunkenness.

Washington Irving changed all that. The author who based so many of his best-loved tales on the people and places of the valley (and who got inspiration for some while rambling through the grounds of Scenic Hudson’s Poets’ Walk Park) loved the Christmas traditions he saw during visits to England beginning in 1815. Through his writing, he began lobbying for their adoption back in the States, both because they brought people together and helped offset the dreariness of winter.

Along with his masterpiece “The Legend of Sleepy Hollow,” Irving’s The Sketch Book of Geoffrey Crayon, Gent., published in 1819, features four essays talking up the joys of an English Christmas — lavish dinners, singing and dancing, gift-giving, kissing beneath the mistletoe, sitting before a roaring fire. “Amidst the general call to happiness, the bustle of the spirits, and stir of the affections, which prevail at this period,” he asked, “what bosom can remain insensible?”

Very few, apparently. Quickly, Irving’s notion of a Merry Christmas swept the nation. “While a number of other stories in The Sketch Book were better known, none would have a greater impact on American culture than these four Christmas essays,” Irving biographer Brian Jay Jones notes. “[Irving] did not ‘invent’ the holiday,” adds Burstein, “but he did all he could to make minor customs into major customs — to make them enriching signs of family and social togetherness.”

A sign of Irving’s influence, says Burstein, is that within a decade of The Sketch Book’s publication, “New Yorkers were greeting each other with Christmas wishes, and stores on Broadway extended their hours to accommodate holiday shoppers.” (By then, Irving had become a Hudson Valley resident, living along the banks of the Hudson in Westchester.)

The emergence of Santa Claus

A decade prior to The Sketch Book, Irving also popularized another holiday mainstay: Santa Claus. His A History of New York, a parody of New York’s Dutch roots in America, contains several references to the city’s patron saint. “[I]n the sylvan days of New Amsterdam the good St. Nicholas would often make his appearance in his beloved city of a holiday afternoon, riding jollily among the tree tops or over the roofs of the houses, now and then drawing forth magnificent presents from his breeches pockets and dropping them down the chimneys of his favorites,” he writes.

The St. Nicholas portrayed by Irving is a plump, merry, and pipe-smoking Dutchman — a far cry from the tall, solemn figure venerated in Europe. Charles W. Jones, a prominent scholar of the saint’s history, goes so far as to say, “The significance of Washington Irving in the story of Santa Claus can’t be understated. Without Irving there would be no Santa Claus.”

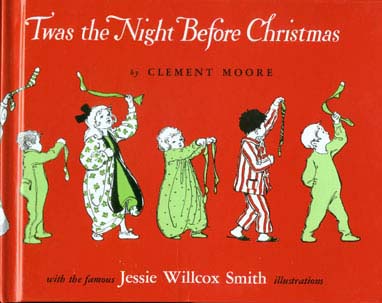

But the Santa known and loved for nearly two centuries owes its existence to a poem published in the Troy Sentinel on Dec. 23, 1823. Originally titled “A Visit from Saint Nicholas,” it later became known by its first five words: “’Twas the Night Before Christmas.”

The poem introduced the world to all the hallmarks of the Santa known worldwide today — his white beard and round belly; the flying sleigh pulled by reindeer Dasher, Prancer, Vixen, etc.; his descent into homes through chimneys. It also changed the traditional date of St. Nicholas’s visit from New Year’s Eve to Christmas Eve.

“The significance of Washington Irving in the story of Santa Claus can’t be understated. Without Irving there would be no Santa Claus.”

Charles W. Jones, St. Nicholas scholar

“A Visit from Saint Nicholas” was published anonymously, which has led to a debate concerning its authorship that has raged for decades. However, the work is generally attributed to Clement Clarke Moore, a professor at Manhattan’s General Theological Seminary. He eventually acknowledged authorship, and included it in a collection of poetry published in 1844.

Whether or not Moore wrote it, the New York Public Library is on the mark when it states that “’Twas the Night Before Christmas” — introduced to the world by a Hudson Valley newspaper — has “left a lasting imprint on American culture, forever changing Christmas lore.”