At the turn of the 20th century, a wealthy lady in New York City wouldn’t think of leaving home for a grand celebration or event without pinning a corsage of violets on her gown. Chances are, that bunch of blooms came from a community in western Dutchess County.

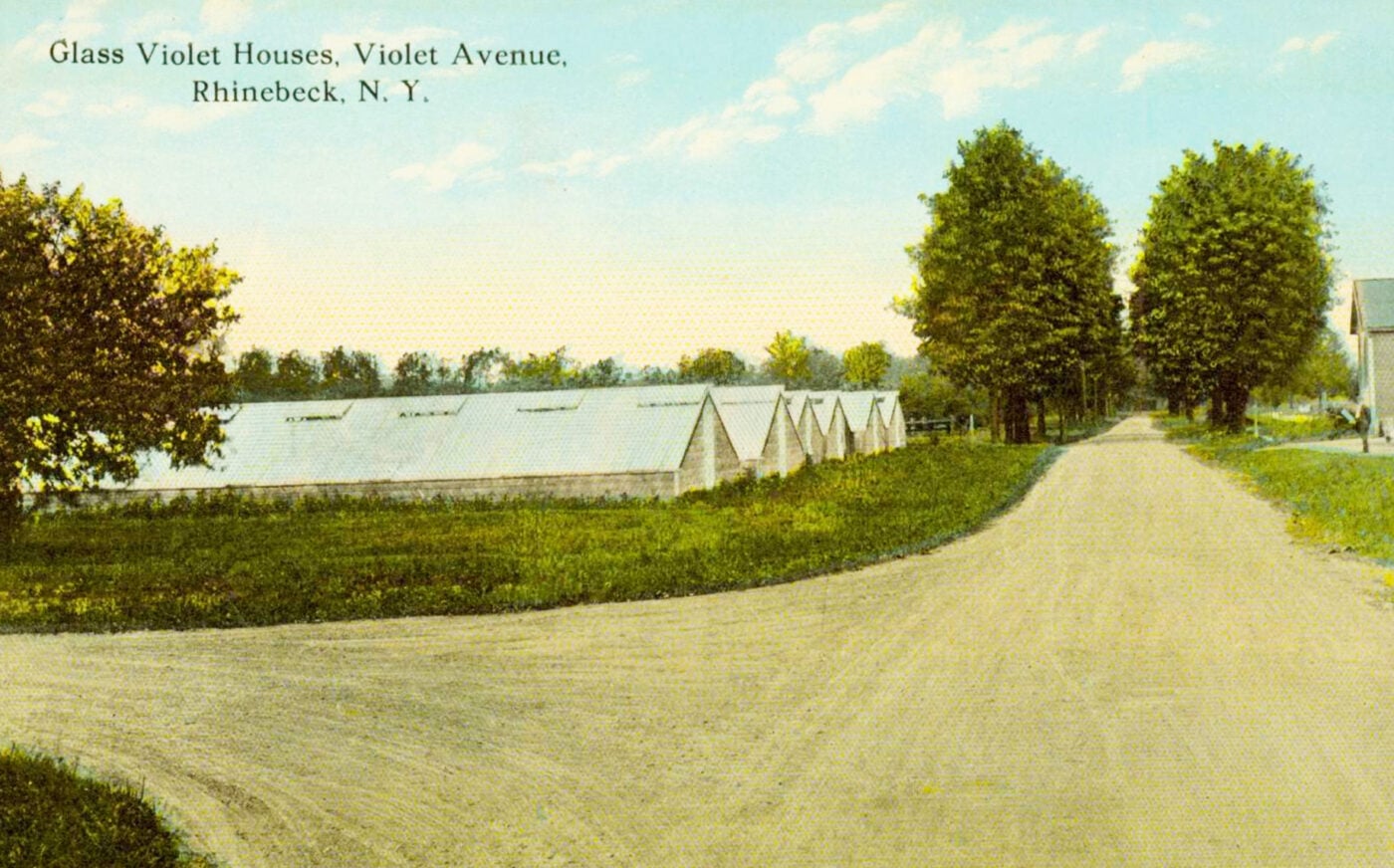

For about 30 years, from the 1890s to the 1920s, growers from Fishkill to Red Hook exported so many of the delicate, pastel-colored, and fragrant flowers that it became known as America’s “Violet Belt.” Pride of place as the belt’s “buckle” belonged to Rhinebeck, which contained up to 400 greenhouses at the height of violet mania. The glare of the sun shining off those expanses of glass gave the village its elegant nickname: the Crystal City.

The boom began when florist William Saltford, an immigrant from England, imported some Marie Louise violets from Europe to grow in his Poughkeepsie greenhouses. Unlike the puny violets that overrun garden beds today — which happen to be edible and make delicious (and colorful) teas and syrups — the Marie Louise (named after Napoleon’s second wife) boasts a profusion of large and sweet-smelling double blossoms. Saltford’s stock, picked and bunched in bouquets, sold out quickly in his flower shop. He shipped some to New York City, where they also became an immediate hit.

Dutchess County’s “blue gold”

Building on his brother’s success, George Saltford established a dedicated violet business in Rhinebeck, and others quickly followed suit — both growers with dozens of greenhouses and mom-and-pop operations in backyards. Wherever they sprouted, the plants required constant care from fall to spring — watering, fertilizing, weeding, tending the coal-fired stoves that heated the greenhouses — until the blooms were prime for picking.

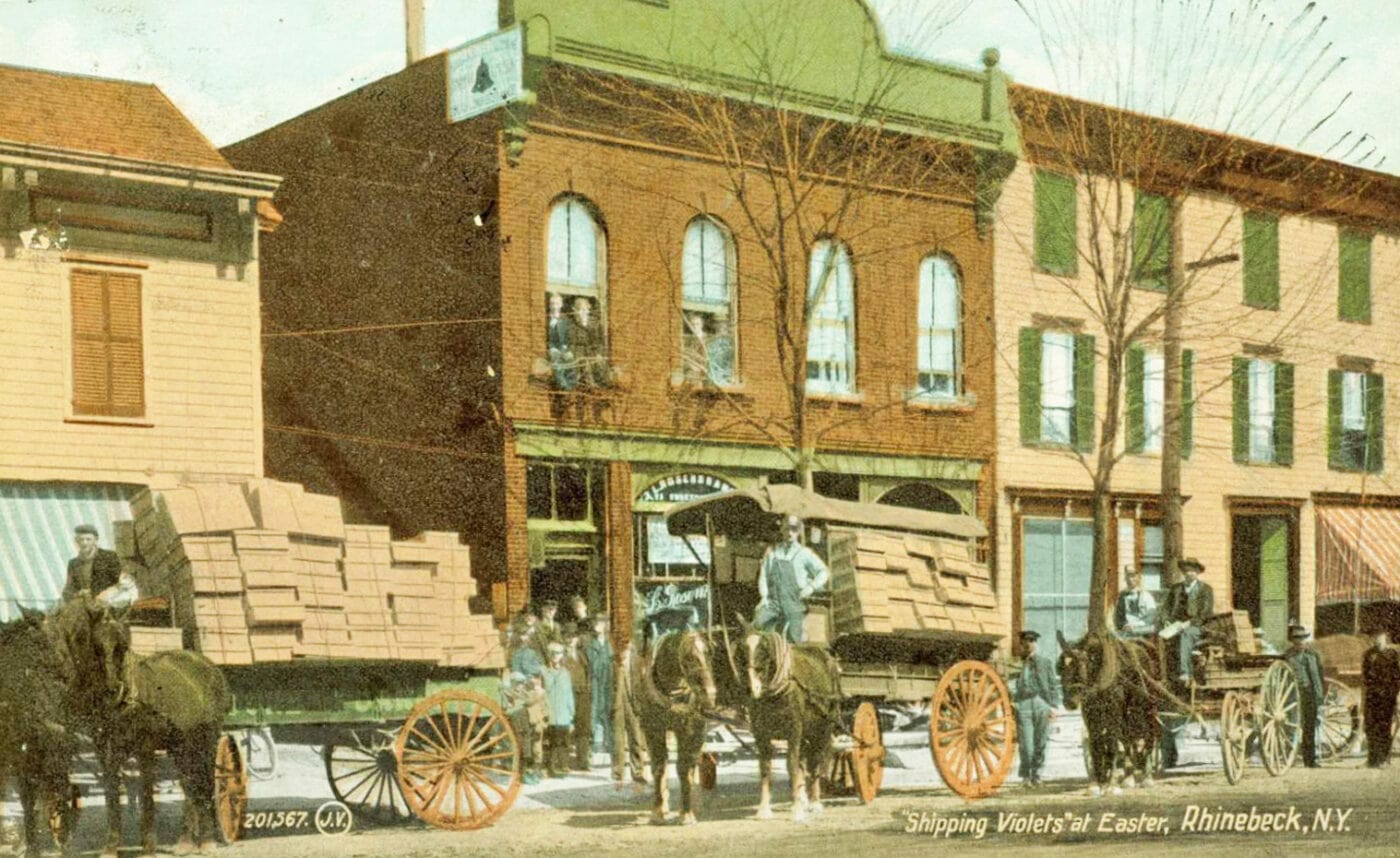

Around Easter, the Super Bowl of violet time, up to 1 million flowers were packed into boxes and loaded on horse-drawn wagons destined for the nearest train station. The sweet smell of success pervaded Rhinebeck and other violet-growing communities for days.

It didn’t take long for Dutchess County to glom onto the economic bonanza, by levying a tax on the plants. For a time, violets were the county’s biggest moneymaker — not surprising when you consider that a single grower, Rhinebeck’s Trombini family, cultivated 6 million violets per year. Overall, the region’s greenhouses harvested as many as 50 million flowers, which were called “blue gold,” annually.

The craze for violets wasn’t limited to Manhattan. Loaded on special trains, including one called the “Violet Special,” they made their way to Boston, Philadelphia, and even Chicago. They appeared in Christmas centerpieces, bridal bouquets, and corsages celebrating everything from Valentine’s Day to the Yale-Harvard football game. They also featured in culinary creations, including violet candy and jelly.

A victim of the Jazz Age

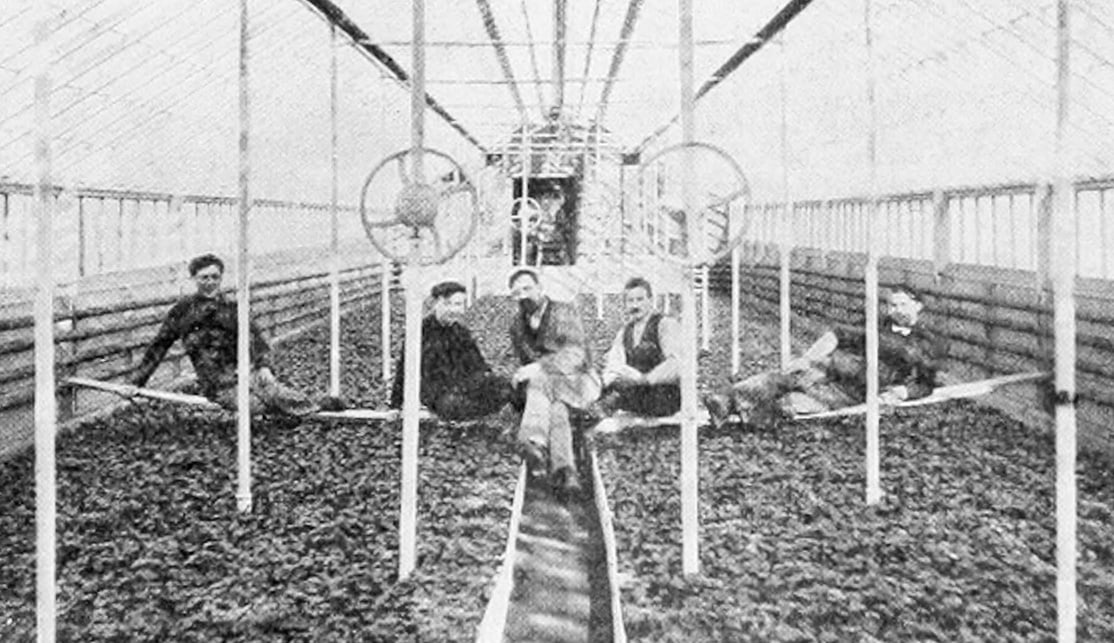

Harvesting such a delicate flower required an enormous amount of work from a specialized team. Pickers straddled boards placed above the beds — a top-notch picker could pluck 5,000 stems a day. “Leafers” surrounded the blossoms with a necklace of violet greenery, and sometimes a paper doily, before tying the bouquet with string. Packers loaded them into specially made wooden crates. Around holidays, housewives and schoolchildren would help meet demand, earning about $3 for 10 hours of work.

What was it about this region that made it so hospitable for violets? Horticultural experts aren’t sure, although all the communities that became centers for growing the plants contain a soil known as Dutchess stony loam. Filled with sand particles and studded with small stones, it requires considerable fertilization to be productive. It’s not ideal for cultivating vegetables, but apple trees thrive in it (hence, the many orchards in Red Hook). So did violets for a season — growers had to replace the soil yearly, at considerable expense.

The bottom started falling out of the violet boom in the Roaring Twenties. A number of factors did it in, beginning with a change in fashion. As a Poughkeepsie newspaper at the time bemoaned, “Women don’t wear enough clothes to hold up a corsage.” In that anything-goes era of the flapper, violets just weren’t considered hip. They hearkened back to the Victorian era.

At the same time, new manufacturing businesses in the region offered higher-paying and less labor-intensive employment opportunities for greenhouse workers. It also didn’t help that the lesbian protagonists of the 1926 Broadway play “The Captive” traded bouquets of violets as a sign of their then-controversial affection. Though the flower has been a symbol of lesbian love for 2,000 years, violet growers, perhaps in search of an easy scapegoat, cursed the play for dooming their business.

Many greenhouses gave up the ghost in that decade. Others soldiered on, enjoying a brief renewal of success in the 1930s thanks in part to the example set by Eleanor Roosevelt, who sported locally grown corsages at her husband’s inaugurations. Rhinebeck’s last violet holdout finally shut down in 1979. Today, the only place to get a bunch is Battenfeld’s Anemone Farm in Red Hook. Carrying on the tradition that started their business five generations ago, the family continues devoting a small portion of their greenhouse to the humble Viola odorata.

Reed Sparling is a staff writer and historian at Scenic Hudson. He is the former editor of Hudson Valley Magazine, and currently co-edits the Hudson River Valley Review, a scholarly journal published by the Hudson River Valley Institute at Marist College.