They fought for working women’s rights, advocated for vulnerable children, even rescued drowning sailors. And of course, they called for cleaner river water and greater public access to the Hudson Valley’s natural abundance. To celebrate Women’s History Month, reflect on the commitment and courage of seven valley women who deserve great credit for blazing new trails. The quality of life in the region today owes them each real debts.

Jane Bolin:

Pioneering Advocate for Children

Jane Bolin (1908-2007) devoted her 30-year judicial career to fighting for women and children who faced discrimination.

She grew up in Poughkeepsie as the daughter of an English mother and a father of both Indigenous and Black heritage. Her mixed background meant she couldn’t shop in some stores, and a then-segregated Vassar College refused her admission. She went to Wellesley instead and then Yale Law School, where she was the first Black woman to graduate. Bolin endured violence and discrimination at both schools, especially Yale, where students from the South intentionally slammed doors in her face.

In 1939, New York City Mayor Fiorello LaGuardia appointed Bolin to the Domestic Relations Court (later renamed Family Court), making her the nation’s first Black female judge. From then until her retirement in 1970, Bolin filled her docket with thorny cases such as juvenile delinquency and child and spousal abuse. She also reformed the judicial system, ending rules that used race as the basis for assigning probation officers and placing children in care agencies, and she assisted Eleanor Roosevelt in establishing the Wiltwyck School, a racially integrated center for at-risk boys in Ulster County.

Summing up her pathbreaking career, Bolin said, “Families and children are so important to our society, and to dedicate your life to trying to improve their lives is completely satisfying.”

Kate Mullany:

Standing Up for Labor Justice

Kate Mullany (1845-1906) started working in a Troy laundry, washing, starching, and ironing detachable collars to support her Irish immigrant family. To keep clean this indispensable part of the 19th-century American man’s wardrobe (90% of detachable collars were manufactured in Troy, earning it the nickname the “Collar City”), Mullany and 3,000 colleagues toiled through 12- to 14-hour shifts, enduring hazardous and unhealthy conditions for about $3 a week ($53 today).

In February 1864, just a few months into the job, Mullany realized something had to change. Noticing that male neighbors belonging to unions had successfully campaigned for higher pay and other concessions, she mobilized 300 of her fellow workers to form the Collar Laundry Union, the country’s first female union.

Shortly after, the women went on strike, demanding a 25% pay increase and safer working conditions. Within the week, employers met their demands — a huge victory.

Until her death, Mullany kept working tirelessly to improve the workplace for women in Troy (where her house is now a National Historic Site) and across America. The reply she once made to a reporter who questioned women’s ability to unionize showed her resolve: “You show me the women and I’ll turn them into organizers.”

Toshi Seeger:

Brains Behind the Clearwater

Folk singer Pete Seeger freely admitted that his wife Toshi (1922-2013) was the “brains of the family.” “I’d get an idea and wouldn’t know how to make it work, and she’d figure out how to make it work,” he said.

Case in point: Her oft-overlooked role in turning the concept of a “classroom of the waves” into reality via creation of the nonprofit Hudson River Sloop Clearwater. This May, 66 years after the Seegers co-founded the organization, its namesake ship will continue connecting children and families with the beauty of the river while educating them about ongoing threats it faces.

Toshi Seeger also came up with the notion of holding an annual musical jamboree to support the Clearwater and its mission — the popular Great Hudson River Revival, a.k.a. the Clearwater Festival. Since 1978, it has drawn hundreds of thousands of people to the river for (as its inaugural program stated) “a celebration of our music, our awareness of our various ethnic heritages and our natural environment.” The festival’s zero-waste ethic — way ahead of its time — also traces its origins to Toshi Seeger.

While not outspoken like her husband, Toshi Seeger also stood up for her beliefs. Together, they joined Rev. Martin Luther King, Jr., in the 1965 march from Selma to Montgomery, Alabama, a landmark moment in the civil rights movement. When Pete sang to protest the Vietnam War, Toshi often was by his side. Yet she escaped notice and acclaim. As Pete Seeger biographer David Dunaway wrote, “Because Toshi was a woman, and because she disliked the spotlight, she never received her due.”

Katharine St. George:

Champion of Women’s Rights

As a conservative Republican who represented portions of Rockland, Orange, Sullivan, and Delaware counties in Congress from 1947 to 1965, Katharine St. George (1894-1983) was the political polar opposite of her first cousin, Franklin D. Roosevelt. But she skewed from her own party’s line when it came to rights for women.

As early as the 1950s, St. George proposed legislation banning wage discrimination against women, coining the phrase “equal pay for equal work.” She achieved her goal in 1963, when President Kennedy signed the Equal Pay Act.

The following year, St. George joined fellow Congresswomen to demand the Civil Rights Act make it unlawful for employers to discriminate against people based on sex (along with race, color, religion, and national origin.) “We are entitled to this little crumb of equality,” St. George said on the House floor. “The addition of that little, terrifying word ‘s-e-x’ will not hurt this legislation in any way. In fact, it will improve it. It will make it comprehensive. It will make it logical. It will make it right.” In part as a result of her persuasiveness, the act contains the “little, terrifying word.”

St. George bristled at being called a feminist, but through her actions she did much to advance the cause of women. “I think women are quite capable of holding their own if they’re given the opportunity,” she said. “What I wanted them to have was the opportunity.”

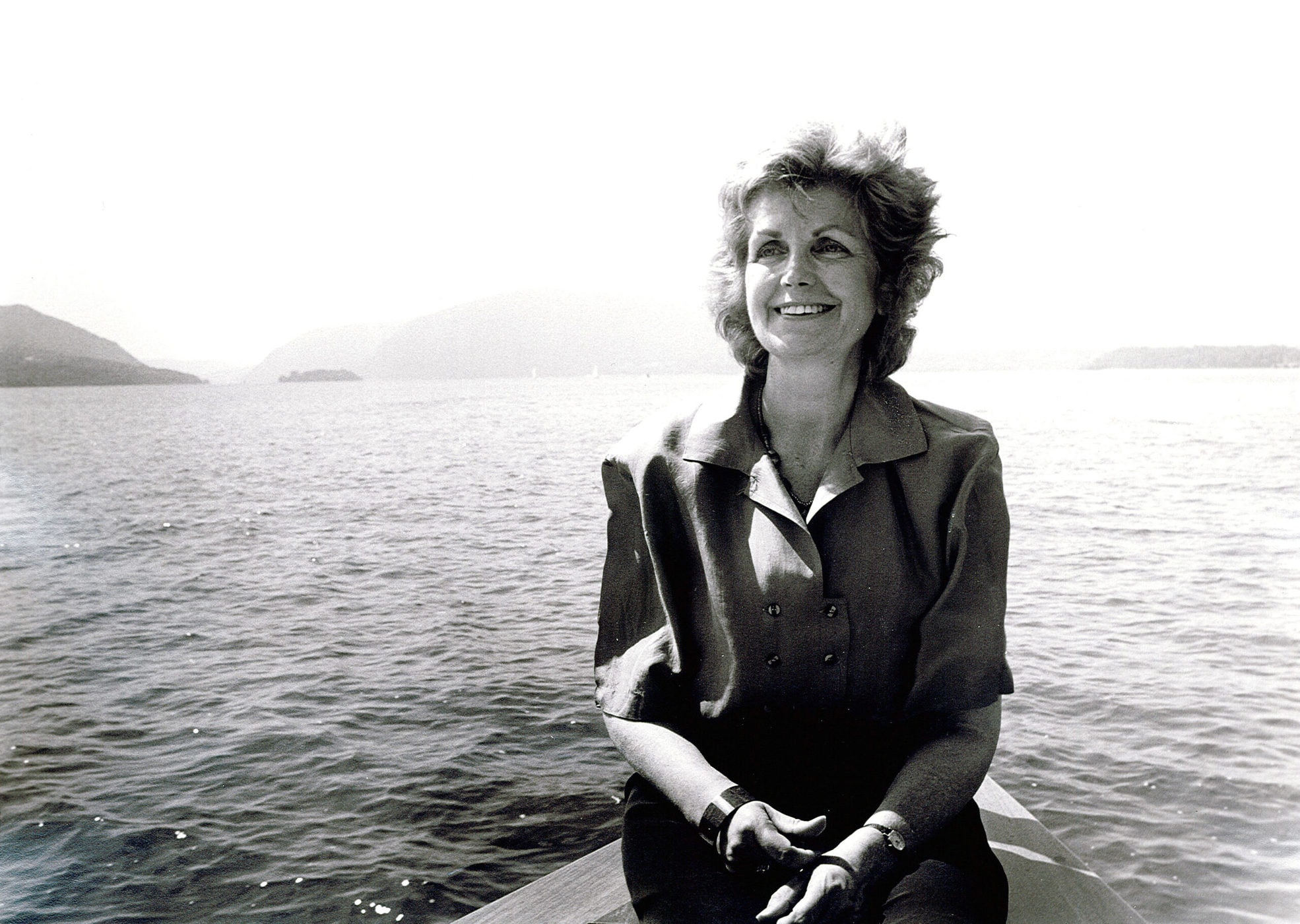

Klara Sauer:

Partnering for a Beautiful Valley

Did they have that “fire in the belly”? That’s what Klara Sauer (1935-2015) considered when hiring colleagues at Scenic Hudson, where she served as executive director from 1979-99. Throughout her life she had demonstrated that fire: Growing up in Germany, Sauer hunkered in a basement as protection from Allied bombers. Eventually immigrating to America, she had to help support family members and then care for her children. But her obligations didn’t dampen her desire for a college degree, which she earned at age 34.

Scenic Hudson was completing its long battle to protect Storm King Mountain when Sauer took leadership. Over the next 20 years, the organization helped reshape the prevailing “us vs. them” mentality of the U.S. environmental movement by fostering collaboration. Partnering with governments and businesses, Scenic Hudson conserved 20,000 acres of land, created 19 public parks, and halted dozens of subpar industrial and residential projects.

In her typical collaborative style, she spearheaded establishment of the Hudson River Valley Greenway. Since 1991, it has provided state resources to help communities preserve the region’s scenic, historic, and cultural resources. A primary goal of Sauer’s greenway vision — creating a multi-use trail from Manhattan to Washington County — became reality in 2020, with the opening of the Empire State Trail.

“Klara’s fierce passion, drive, and determination, laced with a more-than-healthy amount of human kindness, led her to become one of the Hudson Valley’s most respected environmentalists and relied-upon protectors of this special place,” said Steve Rosenberg, former executive director of The Scenic Hudson Land Trust. “Perhaps even more powerful was her belief that beauty had the intrinsic power to make the world better.”

Kate and Ellen Crowley:

Saving Lives on the Hudson

Female lighthouse keepers weren’t rare in the 19th century, even in the Hudson Valley, but few could match the fearlessness of Kate Crowley. With help from her sister Ellen, she tended the Saugerties lighthouse, taking over the duties from her invalid father as a teenager before receiving official appointment to the post at age 20 in 1873.

While the work was by and large routine — illuminating the beacon that alerted ships of the shallows at the mouth of Esopus Creek — the women earned nationwide renown for fearlessly responding to sailors in distress. On a number of occasions, they rowed into storm-tossed waters to pluck drowning mariners from the river.

At a time when few women were proficient at handling oars, the sisters earned great respect from veteran river pilots, not known for dishing out compliments. One called them “two gals as has-got-grit-enough,” while another dubbed them “bricks,” adding, “You couldn’t have got any river boatmen to do what those girls did.”

The sisters, who remained on duty at the lighthouse until 1885, seemed blasé about their derring-do. “We have not the opportunity of making ourselves heroines,” Ellen said, “but we do what we can…”