Normally, people who build hiking trails are a fun, collegial bunch — nature lovers united to blaze a path so others can share their enthusiasm for the outdoors. But in the 1920s and ’30s, the competition to create new trails in and around Harriman State Park took a decidedly confrontational turn. It led not only to what was dubbed the Great Ramapo Trail War, but also to the resurgence of the greatest guardian and maintainer of the Hudson Valley’s hiking trails: the New York-New Jersey Trail Conference (NYNJTC).

Prior to this “conflict,” trail-building in Harriman and Bear Mountain State Parks had proceeded peacefully under the supervision of Major William A. Welch. As general manager of the Palisades Interstate Park, he oversaw every aspect of infrastructure required to connect people to the land — dams, parkways, campsites, bridges, and trails. To facilitate creation of the latter, he founded the Palisades Interstate Park Trail Conference, forerunner of the NYNJTC. It united hiking clubs in the New York metropolitan region (including the all-female Inkowa Club) to create new pathways for enjoying the outdoors.

“Like the legions of the sorcerer’s apprentice“

With Welch serving as chairman of the trail conference in the early 1920s, its cadre of enthusiastic volunteers, both men and women, did superhuman work. In Harriman State Park alone, they created more than 100 miles of trails as well as the distinctive stone camping shelters still in use today. Then, as the decade came to a close, the need for more trails seemed superfluous and the conference’s work was at an end.

But some members of hiking clubs decided to keep right on blazing. “Like the legions of the sorcerer’s apprentice, these enthusiastic trail cutters knew not when or where to stop,” the book Forest and Crag: A History of Hiking, Trail Blazing and Adventures in the Northeast Mountains reported. What’s more, the trail builders didn’t fancy others horning in on “their” territory.

“A war has broken out on the Seven Hills Trail, a feud among mountain climbers, and the weapons are paint cans and brushes,” was how longtime NYNJTC volunteer Bill Hoeferlin described the fracas. “No less than five different markers adorn the trees from the Torne to Pine Meadow Brook: blue, orange, red and white, white and black are the fighting colors… Each battalion adds another color, and it is likely that more battles will take place. If this keeps on, the trees will soon resemble totem poles.”

(Photo: Bdbox / CC BY-SA 4.0)

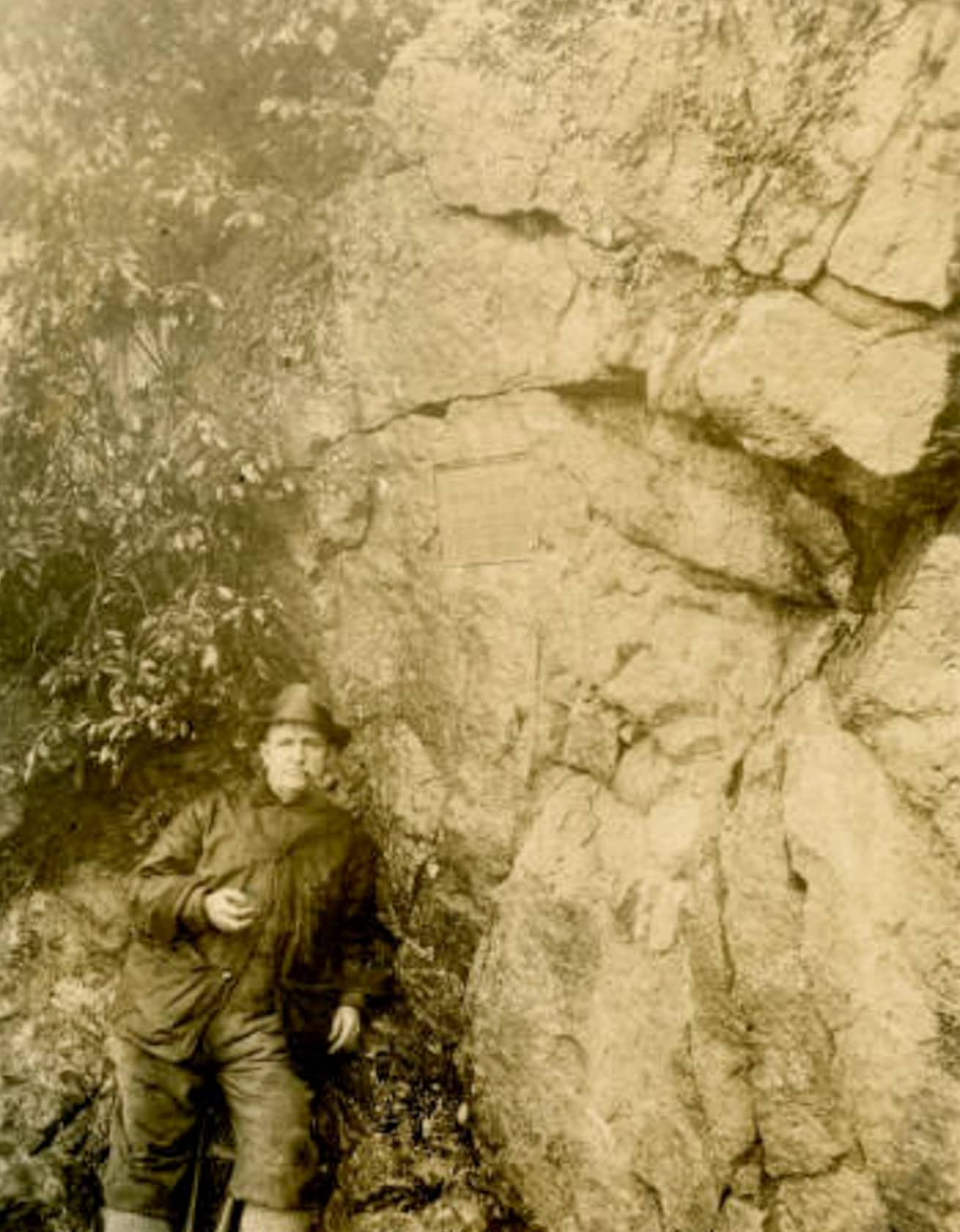

One of the foremost “combatants” in the Great Ramapo Trail War was Kerson Nurian. An electrical engineer who worked on submarines at the Brooklyn Navy Yard, he possessed real skill in blazing routes — many of them, including one bearing his name, continue delighting hikers. On the debit side, Nurian was known for his “independence and insistence on having his own way,” according to the NYNJTC’s Harriman Trails: A Guide and History. “He was an eager trail marker, but never asked permission of the Park, of the Trail Conference, or of the [private] landowners.”

Not content just to add their own distinctive blazes, Nurian and his outlaw cohorts often carried cans of black paint to cover the markers of others before rerouting the trail to their satisfaction. Eventually, a confusing array of paths wound through the woods, posing a directional hazard to hikers and threatening the closure of private lands whose owners had previously allowed hiking on a single, authorized trail.

Diplomacy and arm-twisting

Something had to be done. The first steps were taken in 1931 with the revival of the NYNJTC. Amazingly, almost all of the outlaw trail builders agreed to fall in line behind the organization and abide by its renewed authority to approve new trails. (The NYNJTC also established guidelines for trail colors and the size and spacing of blazes.) Achieving consensus has been attributed to the diplomatic skill — and arm-twisting — of conference chair and journalist Raymond Torrey. He credited a “spirit of harmony and willingness to subordinate individual ideas to the general good.”

Some trail “skirmishes” continued — as late as 1937, Torrey still was complaining to Welch about the “rather absurd situation” Nurian was causing in the Ramapo Plateau by painting over others’ blazes. “He has become furious over what he regards as an invasion of his trail,” Torrey wrote.

Still, by the late ’30s, the war had largely ended, and the NYNJTC had “a new authority and respect it had not enjoyed since the early 1920s,” reported a fascinating history of the conference written in 1995. “This strengthening of the organization was fortunate,” it continued, “for as developers put increased pressure on the Highlands, the [hiking] clubs would need to work closely together to relocate trails and lobby government for land preservation measures.”

Ironically, the man once nicknamed the “Demon Trail Painter of the Ramapos” went on to become an iconic figure in the NYNJTC. Born in Vienna, Joseph Bartha immigrated to the U.S. in 1914 and spent the next 35 years as a maître d’ in New York City restaurants. Every chance he got, he ventured upstate to hike, build trails, and savor the fresh air and natural light. From 1940-55, Bartha served as the NYNJTC’s trail chairman, supervising upkeep of the 500 miles of trails maintained by the organization’s volunteers.

On Bartha’s 95th birthday in 1966, a plaque in his honor was dedicated atop Bear Mountain. When Bartha died three years later, Hoeferlin penned this tribute to him and fellow trail builders: “To them a trail is a living thing, to be cared for, spruced up and opened wide for those who walk in the woods. No orchids for them, no ‘Oscars,’ but the heartfelt appreciation of their fellow hikers and the everlasting satisfaction in their own hearts for a public-spirited job very well done.”