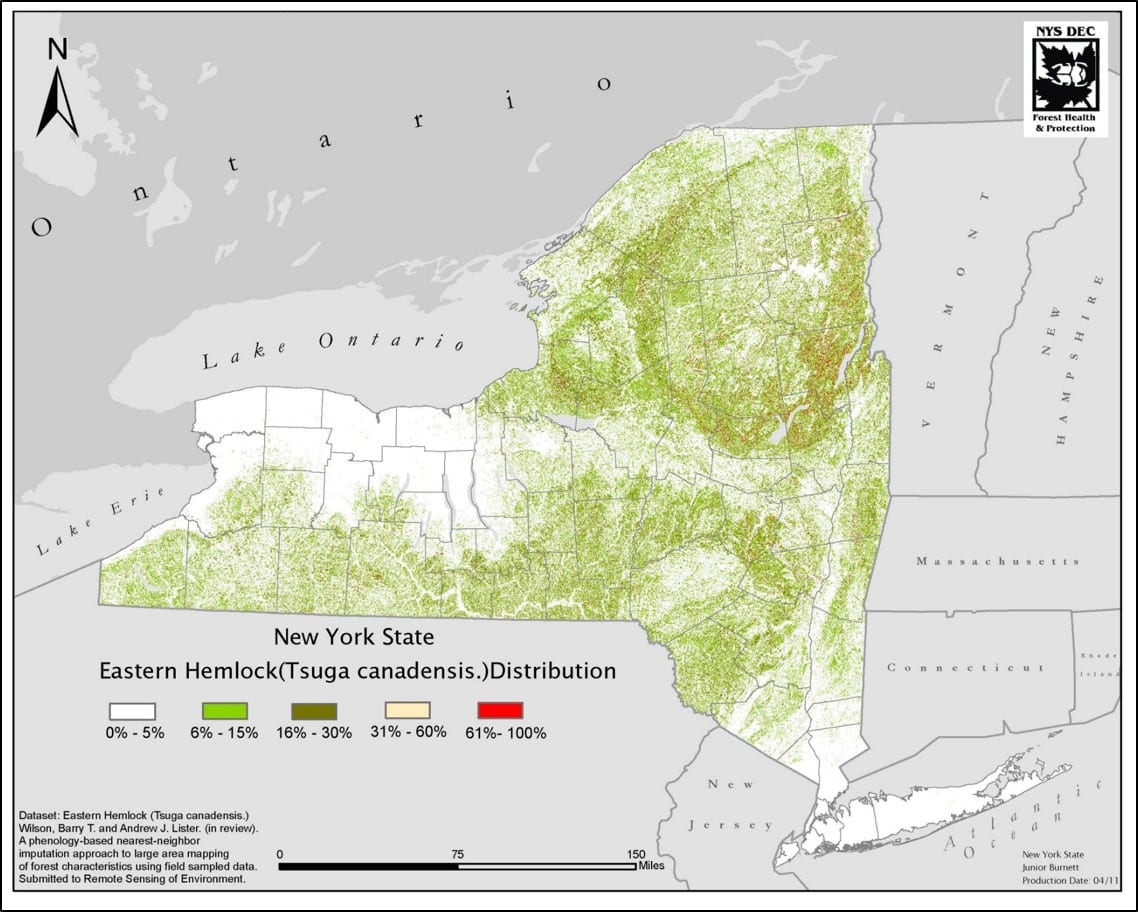

For generations, the canopies provided by the Eastern hemlock trees have been integral to the Empire State’s forest ecosystems. Although more plentiful in the Adirondacks, the Catskills and Hudson Valley area also host the needled evergreen — the Eastern hemlock is the third most common tree in the region.

As centuries have gone by and the inhabitants of the area have changed, the hemlocks have weathered all nature has had to offer, until now. Swaths of Eastern hemlocks in New York State have been hit hard by a never-ending infestation of hemlock woolly adelgid, an invasive insect that’s managed to worm its way into most of the native tree populations in the country. While the pests can still be visible as tiny black nymphs during their period of hibernation (known as aestivation) throughout much of spring and summer, their most noticeable attribute — the white, waxy, “woolly” puffs of material that grow on the base of the needles and twigs — sprout up once winter rolls around in a bid to fight off the cold.

After hitching a ride on a contaminated stock of nursery trees from Southern Japan in the early 20th century, the hemlock woolly adelgid quickly spread all across the East coast, from the southern tip of Nova Scotia all the way to northern Georgia. Even though the adelgid problem in New York has gotten extra attention these last couple of years due to recent outbreaks in the Adirondacks and Finger Lakes, the Catskills have been dealing with these puffy pests since the 1980s, according to Mark C. Whitmore, a forest entomologist at Cornell University’s Department of Natural Resources and the principal researcher at the New York State Hemlock Initiative.

“I think the most important thing is for people to look at the hemlocks and realize how important they are to them. There’s the old adage ‘You don’t know what you got till it’s gone,'” Whitmore says. Whitmore and his colleagues decided to form the Hemlock Initiative to combine their decades worth of research on adelgids as well as raise awareness of the problem on public and private lands. It’s far too late to eradicate the hemlock woolly adelgid; they’ve been detected in 43 counties across the state.

“Basically the short-term fix is treatment with insecticides to keep trees alive,” he says. “The long-term fix is to introduce predators in hopes that we can stop using insecticides at some point in time.”

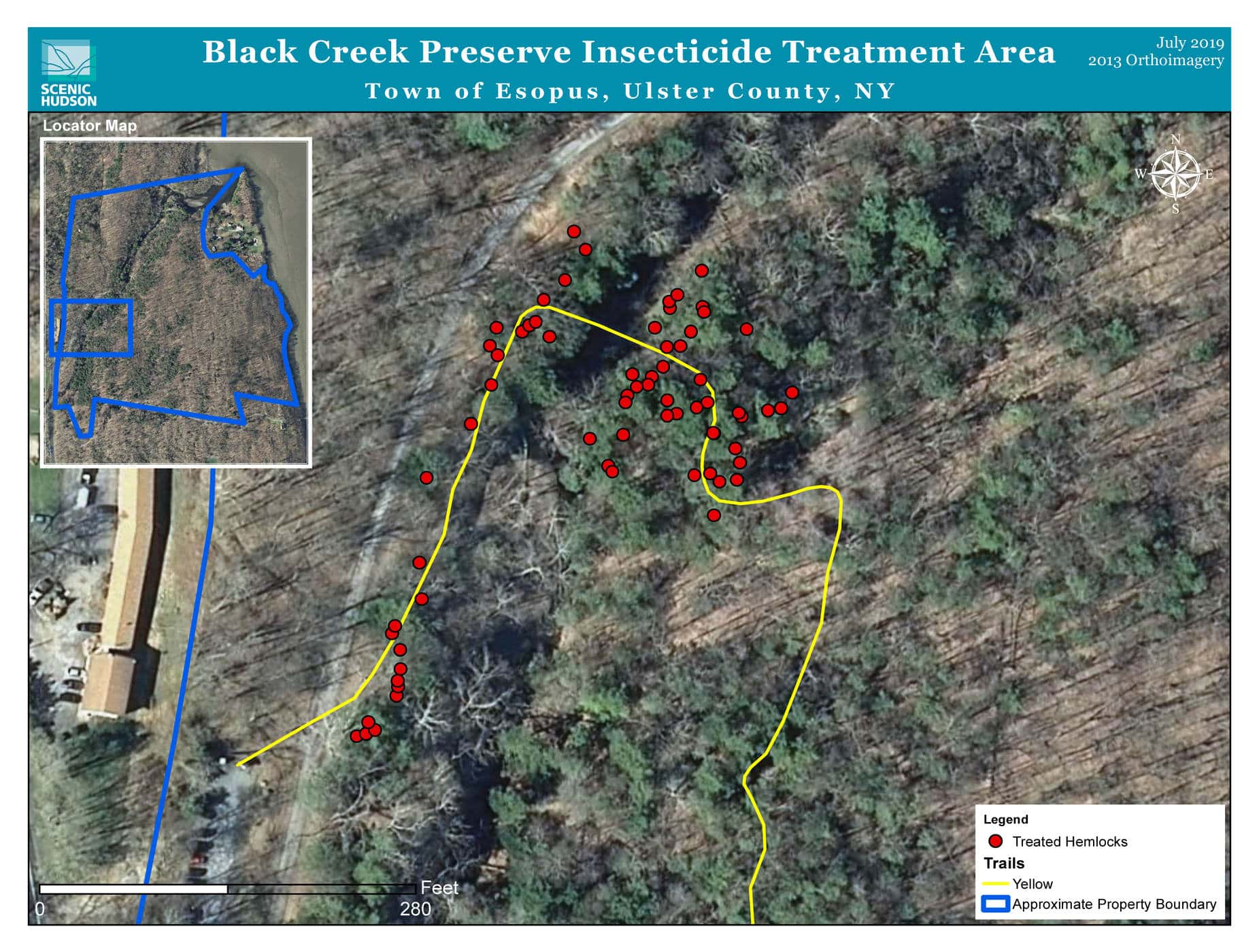

Given the acreage covered by Scenic Hudson’s 45 parks, the Eastern hemlocks within those spaces haven’t been spared either. Land stewardship coordinator Dan Smith and other staff have diligently worked with a certified pesticide applicator over the past year to treat trees afflicted with woolly adelgid on the 130-acre Black Creek Preserve in Esopus. As the adelgid slowly feeds, the tree begins to die from the bottom up as fine twigs with pale greenish-yellowish needles start to pile up and the damage ascends upwards, Smith explains.

“I found a tree on one of our properties this spring that had fallen down in one of the storms and I could see the adelgid in the top of the tree, which I wouldn’t have been able to find if the tree hadn’t fallen down,” he says. The go-to means of treatment tends to be a combination of dinotefuran — a fast-acting sprayable pesticide that kills heavier instances of adelgid — and imidacloprid — a long-lasting pesticide that works its way into the tree’s root system and provides protection for a number of years.

The window to save an infected tree is easy to reach if done early; Smith has heard from some arborists that a hemlock can be saved if around a third or more of the crown is still intact. The chances of the tree surviving are slim once it gets below that point.

With around three-fourths of the state’s forested lands under private ownership, New York’s residents hold a disproportionate amount of responsibility when it comes to salvaging New York’s hemlock forests. In nearby New Jersey, green enthusiasts like Linda Amerman are already doing so by treating the hemlocks on her 1-acre property in Bergen County. As an avid gardener and supporter of native planting, Amerman decided to treat the hemlocks on her property with a store-bought pesticide containing imidacloprid last spring. After successfully staving off the adelgid’s spread, she planted more hemlocks and plans to continue.

“I like the woodlands look of the gardens. Here we have ferns, a lot of shade and a pond, so I like it natural,” Amerman says. “If I can just water my plants with that [pesticide], how easy is that?” She also credits the longevity of the worst-hit trees on her emphasis on cultivating native greenery in her garden; her backyard is both an Audobon Certified Backyard Habitat and National Wildlife Federation-certified wildlife habitat garden.

As a foundation species, hemlocks are a backbone of any healthy forest ecosystem; besides sheltering wildlife, the shade from their towering canopies and underground root networks are crucial to cooling and cleaning nearby bodies of water such as streams and reservoirs.

When he worked on a hemlock project in the Delaware Water Gap National Recreation Area several years ago, Smith saw how the entire makeup of the forest could change once hemlock mortality rates approached 30 percent. “What was regenerating underneath where the hemlocks had died was striped maple and black birch and other kinds of fast-growing, early successional species,” Smith says.

Pesticide use helps curb the spread until Whitmore and other researchers can effectively implement biological control: a form of pest control that uses another predator species that preys explicitly on the target pest. Several years of live testing and tracking out in the field by the Hemlock Initiative team point to two promising candidates: Laricobius beetles and Leucopis silver flies.