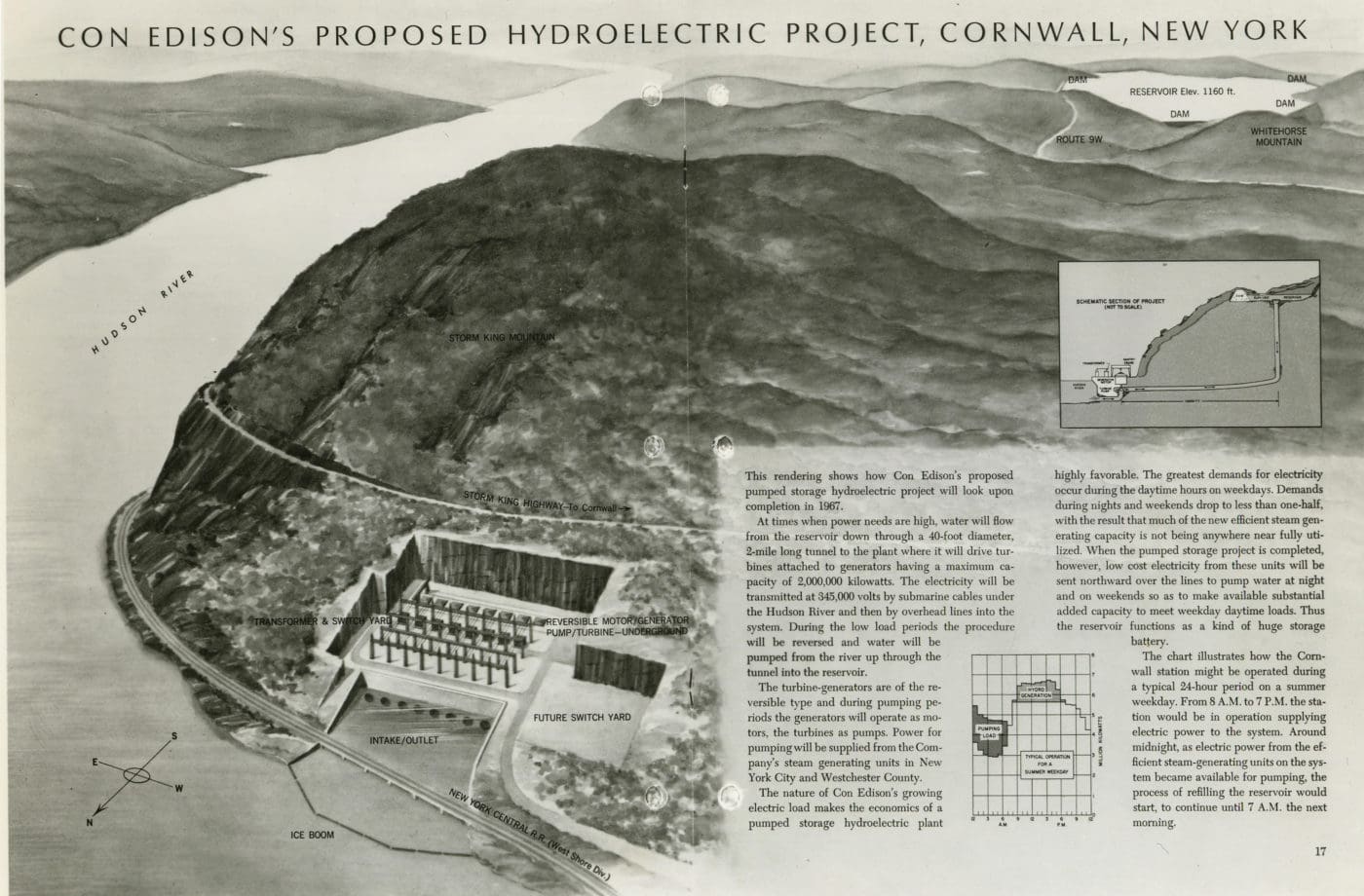

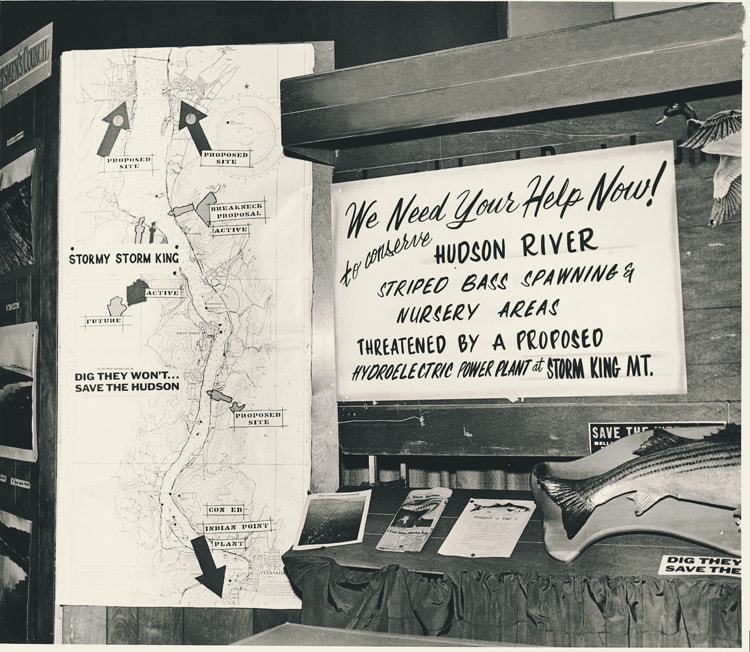

When the 6 people who founded Scenic Hudson gathered to protect Storm King Mountain in 1963, they knew they faced an uphill battle. When it came to big industrial projects like the hydroelectric plant Con Edison proposed to build on this Hudson Highlands landmark, developers and agencies dedicated to their interests held sway over decision-making. Potential impacts on the lives of advertising executives, antiques dealers and school superintendents (the careers of 3 of Scenic Hudson’s founders) didn’t seem to matter.

The Federal Power Commission, which had to license the plant, made this abundantly clear when it denied Scenic Hudson’s request to present their case that by disfiguring Storm King, the plant would destroy the public’s enjoyment of hiking, taking in world-class views and catching fish (whose eggs would be sucked into the facility’s turbines). True to form, the FPC gave Con Ed the go-ahead.

At that point, Scenic Hudson could have folded up its tent. Instead, in 1965 it took the FPC to court, setting the stage for a milestone moment in America’s environmental history — one that would give people a fighting chance forever more to protect the lands and waters they cherish. December 29 marks the 56th anniversary of the “Scenic Hudson” decision, the legal ruling granting people this right.

On the side of Scenic Hudson was Albert Butzel, a young attorney on the case. Of those who were instrumental in getting us to this landmark decision, Butzel is among the last still living. Luckily, he has written a fascinating eyewitness account of the steps leading up to the victory. To celebrate the anniversary, we’re thrilled to share it.

Right case, right time — yet victory surprising

In his reminiscence, Butzel admits the case was a long shot. “To the extent there was hope,” he writes, “it was because, as Bob Dylan sang, ‘the times, they were a-changin’.’ This was 1965, 3 years after Rachel Carson had published Silent Spring, which in many ways changed Americans’ way of thinking about the environment. Increasing concern was being expressed about the new interstate highways being slashed through cherished landscapes, and more and more Americans found themselves impacted by the web of new transmission wires being woven across the country to meet soaring demand for electricity.

“The times, in short, were ripe for a case like Storm King.” Still, Butzel stresses that no one on Scenic Hudson’s side had high hopes.

But to the surprise of everyone, especially the FPC, the Second Circuit U.S. Court of Appeals sided with Scenic Hudson. Its ruling, written by Judge Paul R. Hays, concurs that Storm King Mountain is “located in an area of unique beauty and major historical significance…one of the finest pieces of river scenery in the world.” It goes on to declare that “The principal issue which must be decided is whether the project’s effect on the scenic, historical and recreational values of the area are such that we should deny the application.”

The court’s 3 judges decided unanimously that it was. Their ruling, which took the FPC to task for failing to consider Scenic Hudson’s concerns, forced the commission to restart the licensing process, this time allowing public participation.

Decision paves way for environmental regs, orgs

Today, public input has become such an essential part of determining a project’s fate that it’s hard to imagine the impact this ruling had. For the first time, the “Scenic Hudson decision” gave people the legal right, known as standing, to press their case against industrial or residential developments that could limit benefits they derive from their environment. It stated that natural beauty and the enjoyment of it have value equal to, or even surpassing, a project’s potential profits.

The Scenic Hudson decision paved the way for groundbreaking legislation providing a regulatory framework for giving people a voice, including the National Environmental Policy Act, which requires public input in projects requiring federal approval, as well as New York’s State Environmental Quality Review Act. It also led to the establishment of dozens of new environmental organizations encouraged by this legal milestone.

Butzel, who attributes this great court victory to the eloquence of Scenic Hudson lead attorney Lloyd Garrison, writes modestly, “Neither Lloyd nor I nor any of the others who helped write the briefs had any idea that the case would have the broad implications that it did. We were simply trying to save Storm King.”

That would take 15 more years, a story for another time.