Black Americans have been making important contributions to life in the Hudson Valley since the 17th century, but only in recent decades have their contributions been publicly recognized and celebrated. To continue appreciating Black history well beyond February, explore these 10 sites around the region in a safe, socially distanced way.

Ranging from compelling artworks to historic landmarks, some remind us of the hardships endured by Black Americans, whether during enslavement or while trying to secure their freedom, earn a living or just have a proper burial. Others honor Black people whose words and deeds (and songs) enriched our region and nation. While reminding us of the past, they also inspire us to continue the struggle for fair treatment for all.

Yonkers, Westchester County:

Ella Fitzgerald statue

(Photo: Len Holsborg / Alamy)

Though born in Virginia, the “First Lady of Song” (renowned for her virtuoso scat singing) spent most of her childhood in Yonkers, aspiring to be a dancer. Lucky for us she found her voice, which earned her worldwide acclaim and 13 Grammys. To create this statue, installed in 1996, the city chose Vinnie Bagwell (who also grew up in Yonkers), making her the first African American woman sculptor commissioned by a major municipality to create an artwork. [5 Buena Vista Avenue]

Irvington, Westchester County:

Villa Lewaro

This stately home belonged to Madam C.J. Walker (1867-1919), daughter of Louisiana sharecroppers — and the only sibling in her family not born into enslavement — who became America’s first Black female self-made millionaire. She donated much of her fortune, which she earned by developing and selling hair care products for Black women, to educational and other charitable causes working for fairness and justice. The mansion was designed by Vertner Tandy, the first Black architect registered in New York. [67 North Broadway (Route 9) — the house is private but visible from the street]

Peekskill, Westchester County:

MacGregory Brook

Piermont, Rockland County:

Piermont Paper Mill

This immense machinery, called a flywheel, is all that remains of a factory whose discriminatory hiring practices were all too common in the early 20th century. When workers went on strike, the owners enticed many Black people from the South to take their jobs. Promises of high wages and safe working conditions proved grossly exaggerated — a 1916 account described the new employees’ plight as modern-day enslavement. Worse, workers couldn’t quit before repaying travel costs the company incurred for their migration. [Flywheel Park (Ash Street & Roundhouse Road)]

Goshen-Harriman, Orange County:

Heritage Trail

Travel east to west on this trail — perfect for walking, biking or skiing — and replicate the journey taken by many enslaved African Americans. It sits on the bed of the Erie Railroad, which ran from Jersey City, N.J., to Lake Erie. America’s first long-haul railroad, it provided the quickest way for fugitives to reach Canada. They were helped by abolitionist Orange County residents who provided tickets and rail workers who shunted cars bearing enslaved people onto side tracks to elude federal marshals. [Click for access points]

New Paltz, Ulster County:

Historic Huguenot Street

Many don’t realize that by 1750, about 14% of colonial New York’s population were enslaved people, with as many as 10,000 forced to work on Hudson Valley farms. Ironically, New Paltz’s original settlers — who had immigrated to America to escape discrimination — kept up to four enslaved Africans each. Most resided (and were locked in at night) in cramped cellars like those in the Bevier-Elting and Abraham Hasbrouck houses. The cellar in the latter has been interpreted to portray their living conditions. [81 Huguenot Street]

Hyde Park, Dutchess County:

New Guinea Community

Follow the Red Trail to explore vestiges of the African American settlement that existed here from about 1790-1850. At its high point, up to 60 families — both free Black people and those who had escaped enslavement — lived here. Many worked as farm laborers on nearby estates, and several played prominent roles in the Underground Railroad. Today, house foundations and a stone wall along a former road, called Fredonia Lane by the settlers, serve as a testament to the site’s past. [Hackett Hill Park (59 E. Market Street)]

Port Ewen, Ulster County:

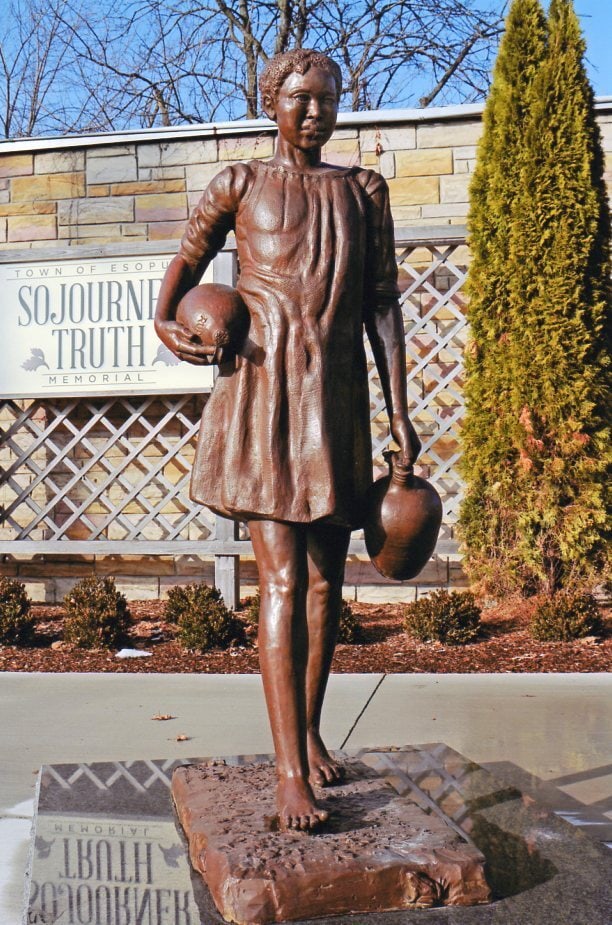

Sojourner Truth Memorial

(Photo: Susan DeMark / Mindful Walker)

During her 29 years of enslavement in Ulster County, Sojourner Truth (1797-1883) worked for local tavern keeper Martinus Schryver, likely performing chores like the one depicted in this sculpture — carrying jugs of molasses used to make rum. Created by Trina Greene in 2013, this is believed to be nation’s only statue depicting an enslaved child at work. At our nearby Shaupeneak Ridge preserve, learn more about the abolitionist and civil rights pioneer on a trail celebrating her life and legacy. [172 Broadway]

Kingston, Ulster County:

Pine Street African Burial Ground

Though this land was acquired for use as a cemetery in 1750, it likely began serving as the final resting place of enslaved Africans in the 1660s. Originally on Kingston’s outskirts (enslaved people were denied church burial), it remained a cemetery until 1853, when it was sold and basically forgotten, though the unmarked graves remained. Protected by the Kingston Land Trust, Scenic Hudson and the local group Harambee in 2019, the latter now is working to restore the site and create a memorial. [157 Pine Street]