When you drive out of the Village of New Paltz, west on Route 299, the Shawangunk Ridge immediately pops into view, towering like a fortress over the farmland below. For many outdoor enthusiasts, this first glance is akin to the Magic Kingdom beckoning to them. After all, the wide expanse of white cliffs is one of the world’s most famous rock-climbing destinations.

It’s easy to see why. Only 85 miles north of New York City, “the Gunks,” known for breathtaking overhangs, sit in a picture-perfect setting and offer up more than 1,200 climbs for every ability and interest. More experienced climbers love how the hard quartz rock tends to form unusual horizontal cracks, which makes for some very challenging routes. Of course, many enthusiasts flock here to be part of the Gunks’ storied tradition, which includes pioneering female climbers, a famous band of counterculture rebels who flipped the climbing world on its head, and today a band of upstart teenagers said to be bringing back the famous ridge’s glory days.

“The Gunks are special,” says Andrew Zalewski, the current owner of Rock & Snow in New Paltz, one of the oldest climbing gear shops in the nation. Growing up in nearby Rosendale, Zalewski knew nada about rock climbing. But after a buddy took him to a local climbing gym in high school, he was instantly hooked. “I chose to study at SUNY New Paltz because I realized that climbing was going to be a big part of my life forever,” he says.

Rock climbing in the Gunks dates to 1935, when German climber Fritz Wiessner, having scrambled to the top of Breakneck Ridge in Cold Spring, spotted the gleaming Gunks in the distance. Within weeks he had scaled and documented the area’s first climb: the Classic Route on the 1,600-foot Millbrook Cliff. He was soon joined by Austrian physician Hans Kraus, who later became President Kennedy’s “secret” personal doctor. Over the next few years the daring duo blazed numerous new routes, including High Exposure, a gasp-inducing sheer cliff face, now considered one of the best and most famous climbs for its difficulty level in the world. (Or as the Mountain Project calls it: “a must-do Gunks mega-classic.”)

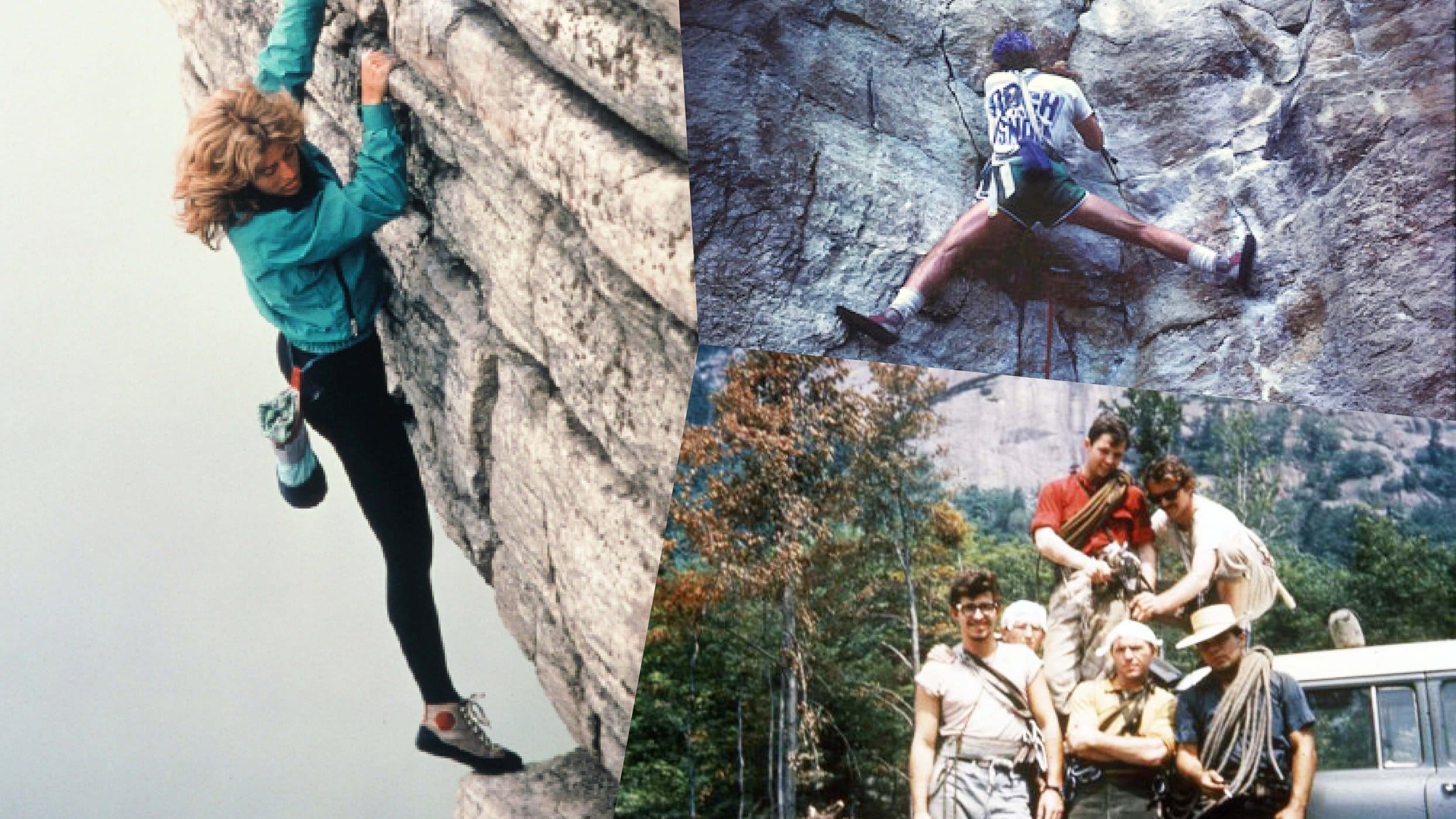

Bonnie Prudden could frequently be found hanging from a cliff alongside Wiessner and Kraus. A professional dancer in New York City by age 10, Prudden shattered her pelvis during a skiing accident at age 23, but went on to become the nation’s first female ski patroller while also claiming 30 first ascents in the Gunks. In 1952, while climbing with Kraus, she forged one of the Gunks’ most popular routes on a formidable ledge sticking straight out at 90 degrees. “It looked like the bottom of a boat jutting out from the cliff. It didn’t seem to have much in the way of standing support,” she later recalled about the daring Bonnie’s Roof.

Kraus also taught Prudden to respect the rocks. “People do not conquer climbs or mountains. The rocks let them pass,” she told Alpinist Magazine. “He showed me how he would lean into the rock’s base and silently ask, ‘May I climb today?’ He would then feel for the answer. You can bet that I did the same thing. If the feeling was wrong, we went to another route.”

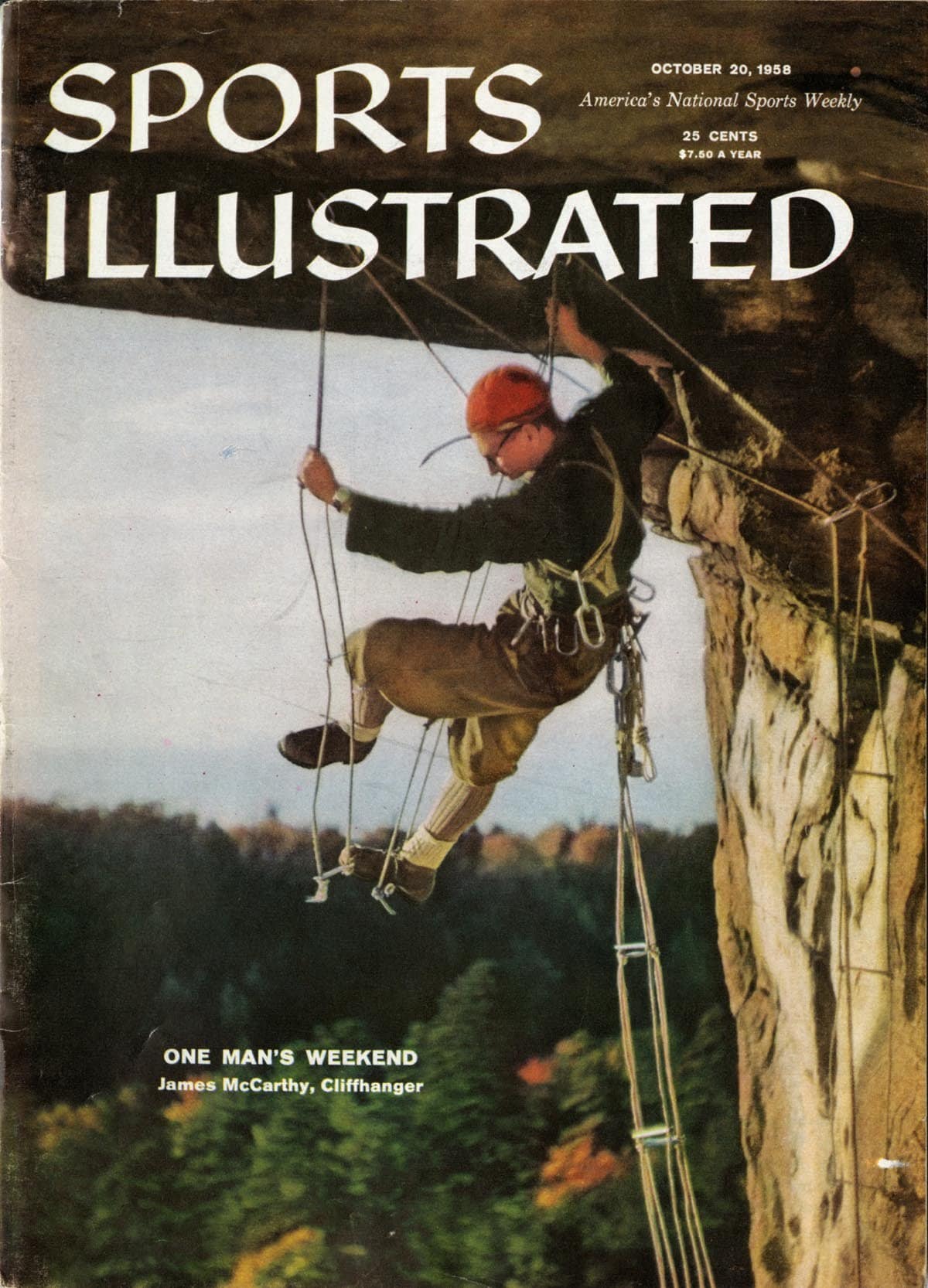

Jim McCarthy, later the president of the American Alpine Club, was known as the best Gunks climber of the 1950s and ’60s. He developed new techniques and forged classic routes, before appearing on the cover of Sports Illustrated in October 1958. McCarthy was hanging from a Gunks ledge, “like a spider” the publication said, on Foops, a difficult route he pioneered. It was the first time rock climbing was featured on the cover of the seminal publication.

By the 1950s, the Appalachian Mountain Club oversaw most climbing activities at the cliffs. Obsessed with safety procedures, perhaps the results of a fatal AMC accident at Arden, N.Y., in 1940, the club started to bristle at other groups, notably college clubs, who started flocking to the area. The bad blood between the strict and sometimes stodgy, “Appies” of the AMC and the rebels, who longed to do their own thing, continued to grow.

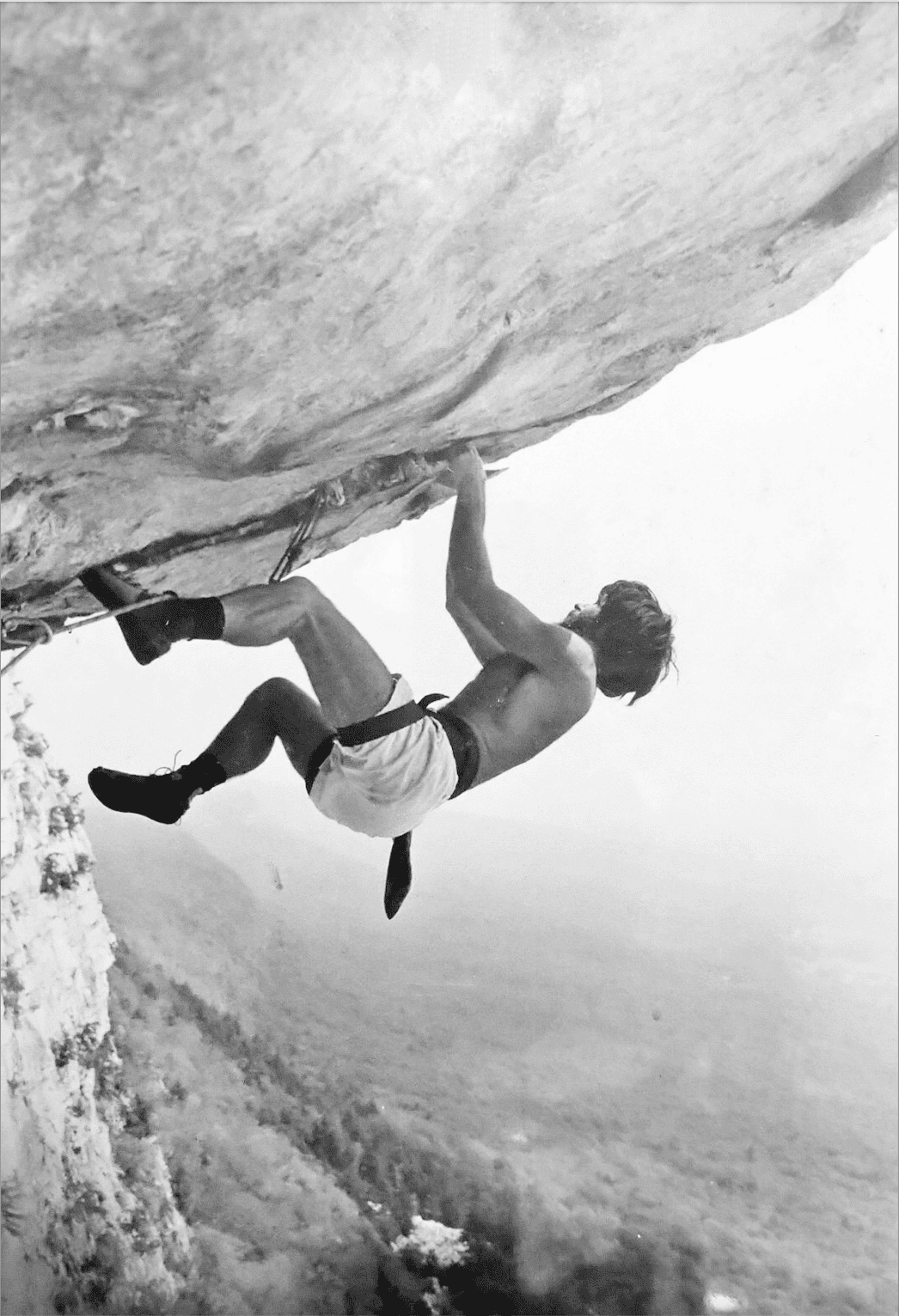

Enter the Vulgarians. A counterculture group of mostly 20-somethings, opposed to climbing rules and regulations, they became as well known for their hard-partying antics — including scaling cliffs in the buff — as they were for their climbing expertise. Camping out in the woods at night was the norm, as was throwing rowdy parties, called raves, at the base of the cliffs. “We’d rave ’til 3 a.m., but we’d always be up and climbing by 9,” says legendary Vulgarian Dick Williams, who went on to found Rock & Snow in an old auto mechanic shop in 1970. Williams’ 1964 nude ascent of Shockley’s Ceiling — with a famous black & white photo as evidence — is still buzzed about today. (To mark the 20th anniversary of this brazen feat, Williams gave fans an encore performance in 1984.)

Eventually, the family who owned the majority of the cliffs allowed the Vulgarians to climb, and the AMC lost control of the Gunks. The result of this new-found freedom: bold, new routes were established across the Gunks. Williams clocked multiple first ascents and in 1964 published the Gunks’ first official guidebook. The Vulgarians also helped diversify the climbing community — opening the sport up from a mostly white, upper-crust pastime to a pursuit for the masses. Suddenly, everybody wanted to climb the Gunks.

“I was part of the matching sweater and knicker socks crew,” says Rich Goldstone about his traditional climbing background. “I was in high school in the 1950s when I first came upon the Vulgarians in a campground in the Tetons. I was completely scandalized! They were partying and doing vulgar things.” Years later, Goldstone, who became famous for several difficult first ascents, as well as for being a bouldering pioneer, “fell in with the very welcoming” Vulgarians in the Gunks.

The 1970s ushered in the era of “clean climbing.” It was becoming increasingly obvious that hammering and extracting pitons was damaging the rock, so the introduction of climbing “nuts” — tools that were placed by hand in existing cracks and then easily removed — mostly replaced pitons. In 1971 John Standard began publishing a newsletter devoted to cliff conservation and educated climbers on how to use the new gear. (In 1967 Stannard had completed the first “free” ascent of Foops — the cliff that had appeared on Sports Illustrated.) By the end of 1972, most of the formerly “aided” routes at the Gunks had been turned to free climbs — and Rock & Snow stopped stocking pitons altogether.

In the late ’70s and early ’80s, Rich Romano became a legend for establishing nearly 50 new routes on the still-intimidating Millbrook cliff. He felt a calling to explore the dangerous rock face. “It’s the most alpine-feeling route, but it’s also spiritual. You either love it or you hate it — there is no in between,” says Romano. “The ’50s and ’60s were fabulous, but the ’70s may have been the best decade at the Gunks. The development was extraordinary. Many people thought I was too brave, but I knew what I was doing.”

One of the best climbers in the history of the sport, Californian Lynn Hill was already raising eyebrows when the 21-year-old instantly “fell in love” with the Gunks on a quick trip East — and moved to New Paltz lickety split to spend the late ’80s and early ’90s conquering the local cliffs. Performing the first free ascent of Vandals, the East Coast’s most difficult route at the time, was just one of the many feats that brought her international acclaim.

The rise in the ’80s of sport climbing, where climbers clip into pre-drilled permanent bolts, caused grave concern in the Gunks. Mid-decade, the Mohonk Preserve, which owns a large perentage of the cliffs, officially banned placing new bolts in the rock, turning the Gunks into a fully “traditional” climbing area. While a few bolted climbs remain at the Gunks, there are no sport climbs at all. Today, the Gunks are considered one of the best moderate “trad” climbing regions in the world.

While the ban was good for the cliffs, it was not so good for keeping the Gunks in the forefront of new climbing innovations. “Most hard modern climbs require the use of bolts drilled into the rock and left there,” says Zalewski. “So this ban made it difficult — and very risky — to forge new routes. So many people have moved on to other places where it is allowed.”

In the ’90s, many climbers turned to bouldering — a form of climbing that is performed on small, low rock formations without ropes or harnesses. It was common to see climbers with mats slung over their shoulders walking along the historic Mohonk carriage roads.

Zalewski says that some new routes are still being discovered in the Gunks, noting that Will Moss was a New York City high school student in 2023 when he established the hardest climb in the Gunks, now called Best Things in Life are Free. Moss is among the teenage upstarts who have been bringing fresh attention to the ridge. “It’s now among the hardest climbs in the country,” Zalewski says, “which is quite a feat because doing new routes here often involves quite a bit of risk.”

But Zalewski believes that the Gunks, and rock climbing in general, will continue to attract new devotees, with the same attributes that captivated him. “It’s physically challenging, it’s mentally challenging, it’s problem-solving,” Zalewski says. Sport Climbing was added to the Olympics in 2020, which will also likely increase interest in the activity.

In spring 2024, the Mohonk Mountain House announced the installation of the first Via Ferrata in the Eastern U.S. A recreational activity that involves ascending steep mountain routes by way of a system of fixed cables, rungs, and ladders, it allows participants to experience the thrill of technical rock climbing — with a much easier learning curve. “I think it’ll be a major draw,” says Zalewski. “I did my first Ferrata last year in France; it was awesome.”

He notes that many people are now introduced to the sport through climbing gyms. “In the past, people would get into rock climbing from an interest in hiking and then backpacking. Learning to climb was a way to further explore the outdoors,” he says. “But now, many don’t climb outdoors at all. But if you want, you can go outside and have the same experience as people who pioneered these routes in the ’30s, ’40s and ’50s. It’s all there for you.”