UN researchers estimate that 1 million plant and animal species face extinction. Meanwhile, January 2020 was the warmest in the 141 years of record-keeping. Hoping to roll back alarming statistics like these, a group of scientists have suggested making 30% of the planet a nature preserve by 2030, with an additional 20% to secure our terrestrial carbon sinks and promote climate resilience.

Their ambitious plan, called the Global Deal for Nature, has garnered wide-ranging support since its proposal last spring. Nearly 3 million people worldwide have signed a petition backing it, while several nations—from Costa Rica to Senegal—have begun taking steps to help reach the target.

But would it work? In terms of replenishing habitat, signs definitely point to yes. Animals don’t seem choosy about the lands they occupy, even if they have been degraded by humans. For example, in the decade since residents around the site of Japan’s Fukushima nuclear disaster were forced to leave their homes because of health concerns, more than 20 wildlife species—from Macaques to pheasants—have begun thriving.

“We know from many studies all around the world that when we give space to nature, she comes back spectacularly,” says National Geographic’s Enric Sala. “And we know that when nature comes back, all the services that nature provides for us come back, too.” Those services include sequestering carbon, which is essential for combatting the climate crisis.

The thornier question: Is the Global Deal for Nature doable? About 15% of the Earth’s land mass and 7% of its oceans are currently protected, so there’s a long way to go in a little time. And the forces lined up against its success—timber, large-scale commercial farming and mining industries (groups eager “to make money in the casino of the Titanic after hitting the iceberg,” according to Sala)—have deep pockets and powerful lobbyists.

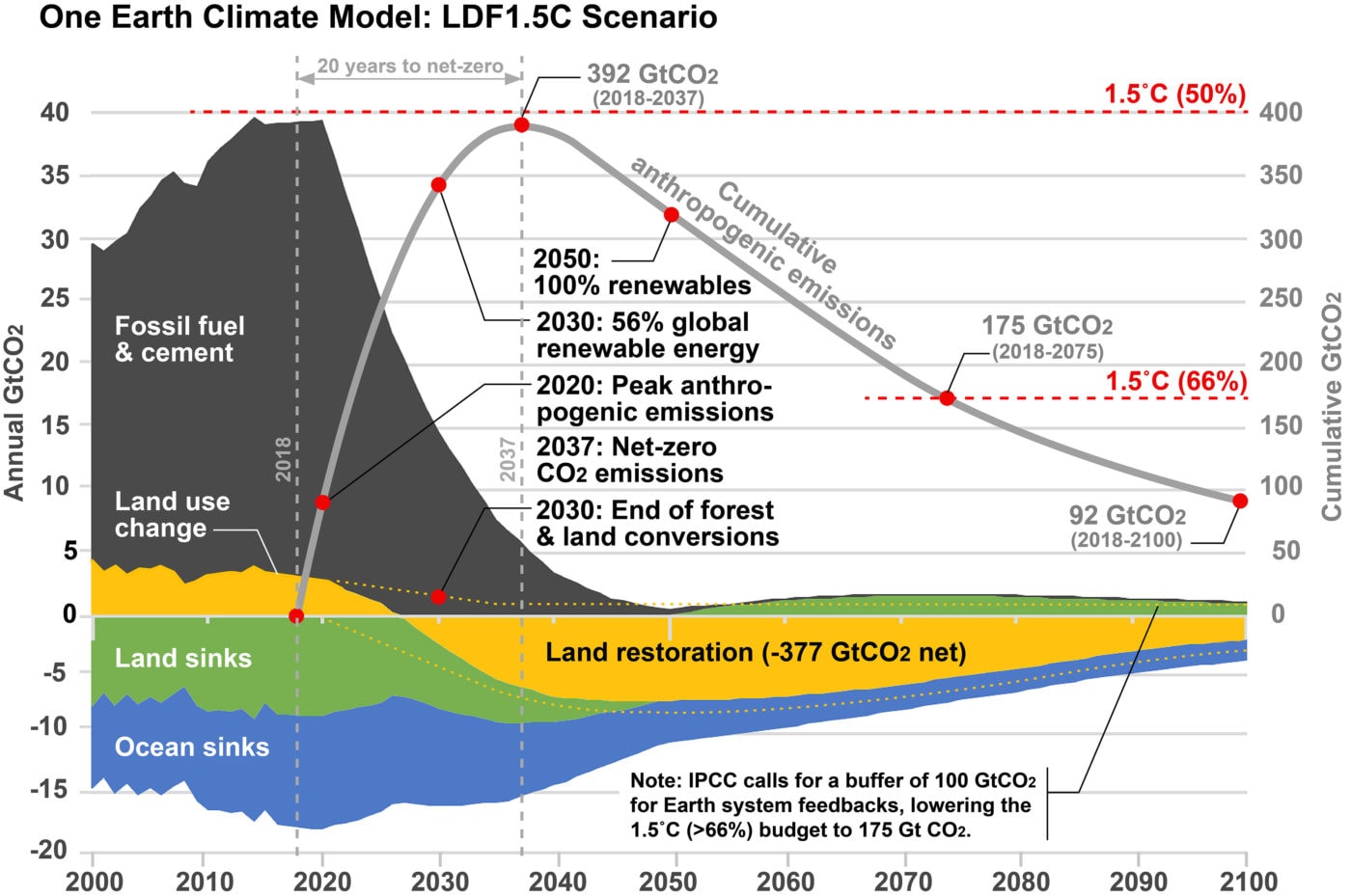

Still, proponents of the Global Deal for Nature remain optimistic for the very reason that the planet’s future depends on it. “Even if [our energy system] went 100% renewable,” notes Sala, “we still need forests and wetlands and healthy ecosystems to help us absorb all the CO2 we’ve put in the atmosphere… There is no solution to climate without biodiversity.”