A decade ago, Bryan Meador was an art student in New York City alienated by too much concrete. He felt far from Oklahoma, where he’d grown up gardening with his Cherokee grandparents. Wandering city streets in search of natural inspiration, he found joy at the Brooklyn Botanic Garden. That gave him an idea. What if more greenery could lace through even the most built-up neighborhoods?

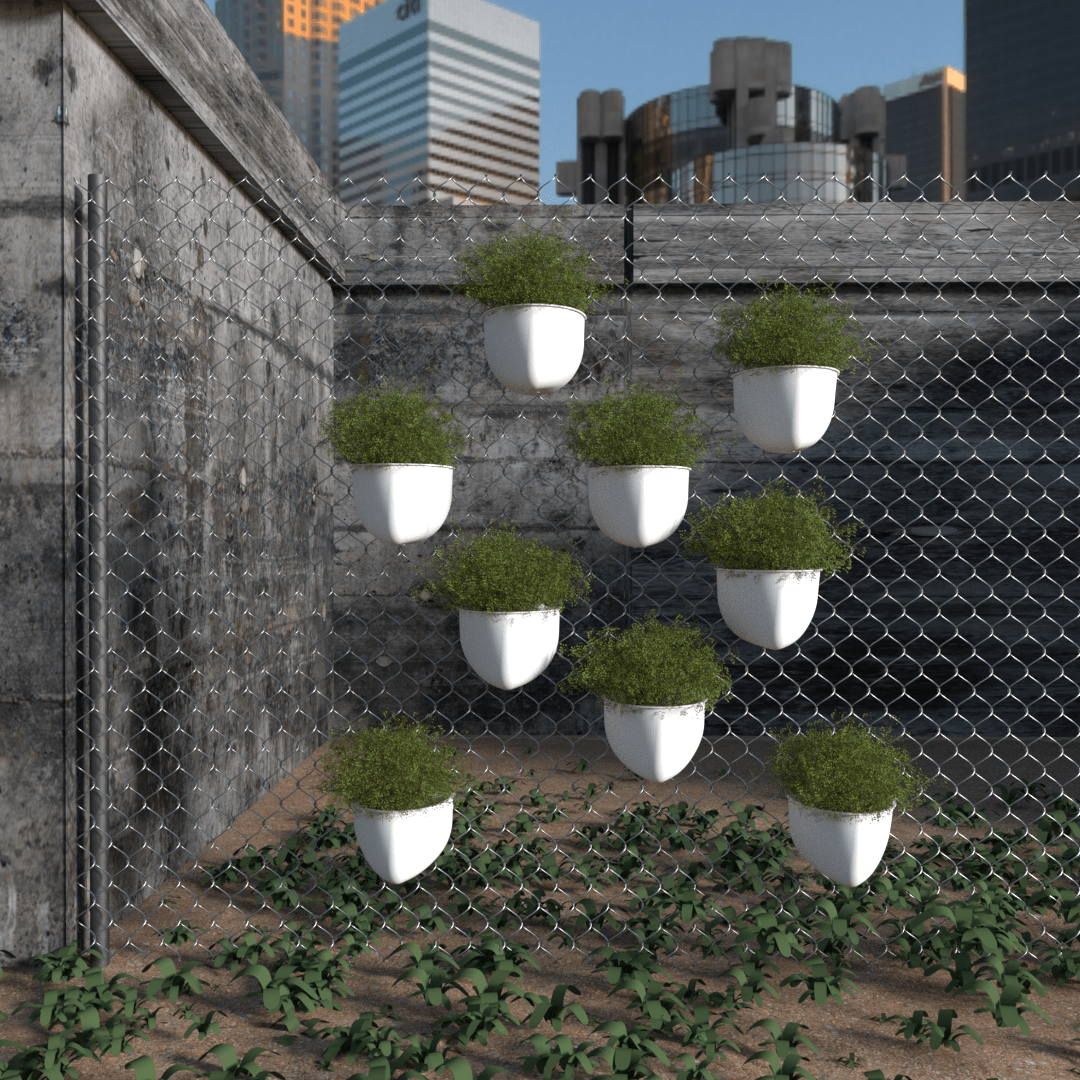

The idea germinated over about eight years. By then Meador had graduated from the Parsons School of Design and begun living upriver in Kingston. Even in the much smaller town, he’d walk toward the Hudson and see acres of chain link fence along the way. In 2018, he started working out a design: the Seadpod, a recycled-plastic microplanter that could hang on chain link in groups, transforming cold metal fences into lush vertical gardens.

Meador’s start-up, Plant Seads (yes, it’s spelled with an “a”—the word is an acronym for Sustainable Ecology, Adaptive Design) is placing its first installations this summer. Fifty will hang in Kingston at the YMCA Farm Project, and more will be placed around Hudson by the Kite’s Nest youth organization.

In Kingston, the vision is to grow plants like climbing peas. Kids can tend them for snack-off-the-vine veggies, but they’ll also cover the fence with blooms (and fill the air with a sweet orange-honey scent). Back in the city, Plant Seads is finalizing plans with organizations like the New York Restoration Project, Harlem Grown, and Grow NYC as well.

Plant Seads is part of a larger global movement toward vertical gardening, which injects green into areas that have no soil in order to reduce heat, improve air quality, and mitigate runoff. Meador, whose mother keeps bees, hopes they can serve as pollinator habitat as well.

“I’m really excited about how these planters can work within the built environment we have right now, offering sound insulation and water absorption and air purification and all the psychological benefits of plants.”

Bryan Meador, creator of Seadpods

As cities densify, using every bit of space will become critical. More plant life has proven benefits to climate and human health, helping people grow food and breathe cleaner air. “The majority of people on this earth live in urban spaces now,” Meador says. “What I’m interested in is the atomization of gardening. One individual has 10 planters, and you multiply that by 1,000—that suddenly becomes a significant amount of organic material injected into the city, and a significant amount of rainwater absorbed.”

Seadpods are true products of the Hudson Valley. Dan Freedman, dean of the School of Science and Engineering at SUNY-New Paltz and head of the Hudson Valley Additive Manufacturing Center, helped Meador perfect the design, along with Dan Young of M-Tech Design, Inc.

At 8.5-by-8.5-by-10 inches, the planters are carefully weighted to hold a gallon of soil each so they won’t collapse a fence. They mount using a keyhole and clamping key so they’ll swing flexibly to withstand high winds. Usheco, a local plastics manufacturer, is producing the containers, which are made from BPA-free recycled milk jugs and retail for $8 each.

At home along the Hudson, vertical Seadpod gardens would ideally act as sponges. Their collective soak-up could help improve water quality in the river. When stormwater overwhelms combined sewer systems, waste goes into streams and on into the river. Seadpods can be a solution to help people hold their rainwater and keep it out of the sewer system.

“By holding onto the rainwater where it is, these planters help the natural aquatic ecosystem.”

Bryan Meador, creator of Seadpods

Have a fence of your own that you’d like to turn into a green wall? Seadpods are available at plantseads.com.