Jacqueline Dooley

Continue readingCandid Camera

What takes place in Scenic Hudson parks once the sun goes down and people go home? A series of motion-activated cameras in the forest at Shaupeneak Ridge and Black Creek Preserve give us a peek into the nocturnal activities of the park’s resident wildlife.

The cameras have been placed strategically to aid work by members of Scenic Hudson’s Science, Climate and Stewardship Team. At Shaupeneak Ridge, they help team members study “connectivity” — how animals pass from one patch of habitat to another — by gauging when (and if) forest-dependent animals move across intervening meadow habitats, roads and developed areas. They also support research into which forest wildlife use the preserve’s seasonal waterbodies, known as vernal pools.

At Black Creek Preserve, the cameras help locate any weak points in a deer exclosure, an area fenced in to support the growth of plants harmed by the animals’ over-browsing.

Still, team members admit part of the thrill of the cameras is discovering what’s “on the roll of film,” so to speak. Since their installation in early 2020, the cameras have taken thousands of infrared, no-flash photographs. Squirrels, turkeys and raccoons figure prominently, though strangely no chipmunks (which may be too small to detect). A fisher and an owl are two of the more exciting animals to be captured. But by far, the most picturesque image is one of a coyote in an early morning light that looks like an artist’s rendering from a bygone era.

What animals would the stewardship team like to find? “I’d really like to see a bear, or a bobcat that’s more than a blur,” says Land Stewardship Coordinator Dan Smith, who maintains the cameras. In time, the team hopes to install more cameras in more of our parks, both for research and to increase the likelihood of exciting new discoveries.

The Mastodon’s Return

A fascinating — and extremely large — piece of Hudson Valley history has returned to America for a brief visit. With any luck, we’ll be able to see it.

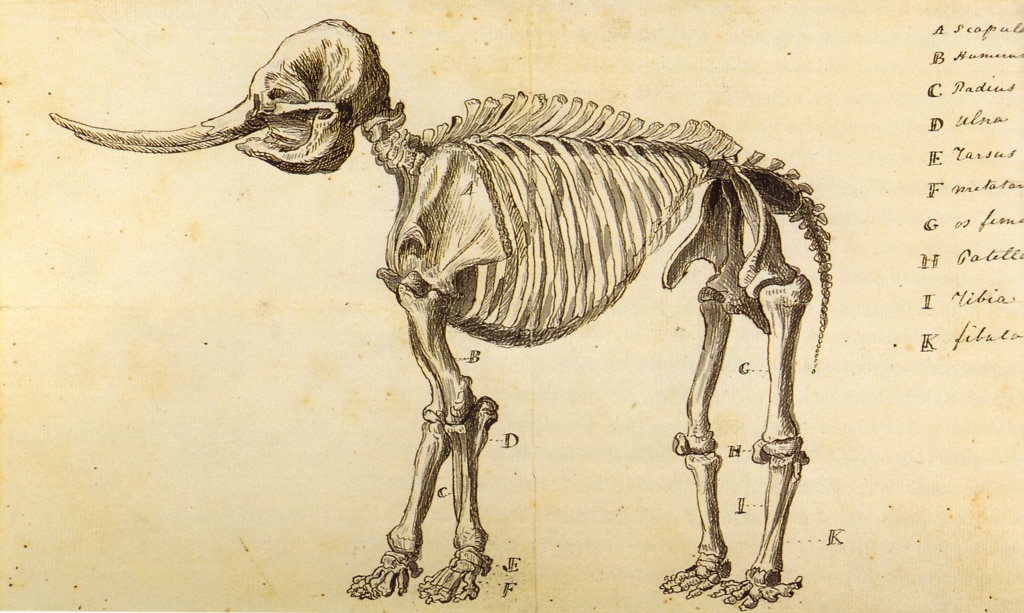

As part of the exhibit “Alexander von Humboldt and the United States: Art, Nature, and Culture,” the Smithsonian Museum of American Art in Washington, D.C., secured the loan of “Peale’s Mastodon” from a museum in Darmstadt, Germany. The bones of this great beast caused a huge stir upon their discovery in 1801 on a farm in Montgomery, Ulster County. In essence, they offered undeniable proof that America had a storied past.

With funding from the federal government — the first ever dedicated to a scientific endeavor — the American Philosophical Society dispatched Charles Willson Peale to recover the remains of this 10,000-year-old mammal. Peale was a wise choice: As well as an accomplished painter, he operated America’s first natural history museum. His painting Exhumation of the Mastodon evinces both his skills as an artist and early paleontologist. It portrays the large team of workers he assembled and the ingenious contraption he devised to prevent water from flooding the dig site.

What made this find truly remarkable was the skeleton’s virtual completeness. Individual mastodon bones had been unearthed around the new nation, but they failed to convey the animal’s immensity. At the time, European scholars ridiculed America for lacking any “important” natural history. They contended that the country’s wildlife sprang from weak, puny ancestors. Here at last—to the great joy of the nation—was solid evidence to the contrary. “There’s a huge amount of civic pride attached to this mastodon skeleton,” explains Smithsonian senior curator Eleanor Harvey. The scientific name accorded the beast — Mammut americanum — honored its country of origin.

For nearly half a century, Peale’s Mastodon proved the main attraction at his Philadelphia museum, attracting thousands of visitors. So how did it wind up in Germany? Following the museum’s closure in the mid-1800s, the Peale family sold it. After spending some time in France and England, the skeleton settled in at Darmstadt’s Hessiches Landesmuseum. (Read this compelling account of curators’ efforts to prepare it for the homeward journey.)

“Alexander von Humboldt and the United States” was scheduled to run from March 20-August 16, but the museum remains closed during the coronavirus crisis. Hope springs eternal that it will reopen in time, or the exhibit’s dates will be revised. And while this most famous of all mastodons eventually will re-cross the Atlantic, a skeleton unearthed in Cohoes in 1866 will continue delighting visitors to the New York State Museum in Albany.

Exhumation of the Mastodon by Charles Willson Peale / Public domain (Credit: From Wikimedia Commons, the free media repository)

Cohoes Mastodon (Photo: O World of Photos on Flicker (CC BY-NC-ND-2.0))

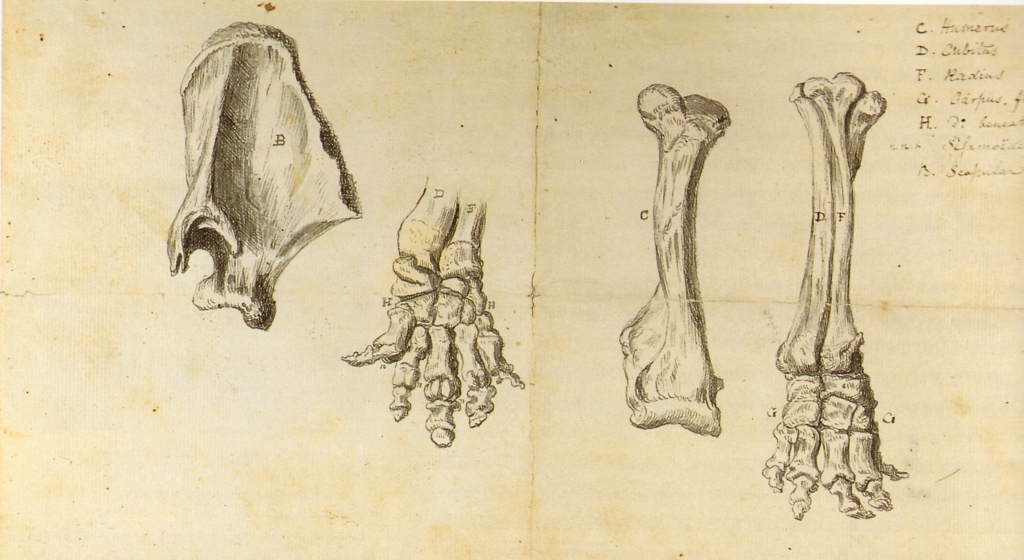

Working Sketch of the Mastodon by Rembrandt Peale (Credit: Rembrandt Peale – Public domain)

Working Sketch of the Mastodon by Rembrandt Peale (Credit: Rembrandt Peale – Public domain)

Current image Peale’s Exhumation of Mastodon site – Montgomery, NY

Big Beasts

Occasionally we hear about mountain lion sightings in the Hudson Valley. And within short order, the stories are usually debunked.

While the DEC states that New York has not sustained a native population of mountain lions (aka cougars) since the late 1800s, the agency does admit there have been occasional, verified sightings of mountain lions that escaped from licensed breeding facilities in the state or, in one very special case, a male cougar who passed through New York on an epic 1,500-mile trek from South Dakota in search of a mate. His quest ended tragically in 2011, when the 140-pound beast was killed while trying to cross a Connecticut parkway.

So while there’s little likelihood you’ll spot a specimen of our nation’s largest cat (even if one is around — they’re extremely shy and excellent at hiding), you have a better opportunity of seeing several large mammals that, while not exactly common, do have a definite presence in the region.

The most prevalent of these are black bears. The DEC estimates that some 3,000 of these hefty omnivores — males weigh up to 300 lbs., females a little over half that — reside in Southeastern New York. Sightings in Westchester and Rockland counties have become more common. In the mid-Valley, black bears wander into backyards with some regularity.

The best way to keep them off your property is to limit their access to food by keeping trash cans lidded, fencing the compost pile and taking down bird feeders once spring arrives. (State law forbids the deliberate feeding of bears.)

If you plan to hike or camp in “bear country,” read these DEC guidelines for avoiding conflicts.

Black Bear (Photo: Jitze Couperus on Flickr (CC BY 2.0))

Black Bear (Photo: Jean-Guy on Flickr (CC BY-NC-ND 2.0))

Black Bear (Photo: Jim Mulhaupt on Flickr (CC BY-NC-ND 2.0))

Black Bear (Photo: Bryan Wilkins on Flickr (CC BY-SA 2.0))

Black Bear (Photo: Bob White on Flickr (CC BY-NC-ND 2.0))

While they lack the heft of cougars, bobcats still elicit a thrill when spotted. Roughly twice the size of house cats, they sport black tufts at the ends of their ears and a stubby (“bobbed”) tail. Bobcats live on both sides of the Hudson, especially in the Catskills and the Taconic Mountains, on the valley’s border with Massachusetts. They roam widely for prey, primarily deer and rabbits, but tend to seek out rocky ledges and rock piles for shelter and breeding.

Bobcats are extremely shy and rarely aggressive, so it’s unlikely you’ll need to take any defensive measures if you’re lucky enough to spot one.

Bobcat (Photo: Valerie on Flickr (CC BY-NC-ND-2.0))

Bobcat (Photo: dbarronoss on Flickr (CC BY-NC-ND-2.0))

Bobcat (Photo: Len Blumin on Flickr (CC BY-NC-ND-2.0))

Bobcat (Photo: Mike McBride on Flickr (CC BY-NC-2.0))

And that brings us to New York’s largest land mammal — the moose. Once prevalent in the Valley, they became extinct here by the late 1800s. As populations in their home range of northern New England have expanded, they’ve begun migrating southward in greater frequency.

Today, they’re occasionally reported in the region and have become permanent residents in the Taconic Mountains. (Still, your best bet for seeing a moose in NY is the Adirondacks; consider a road trip to one of these sighting “hotspots.”) The best time for moose watching is at dawn and twilight, when they feed. Be sure to keep a respectful distance.

Despite their usual shyness, a threatened moose will attack and definitely can outrun you. The last thing you want is to be chased by an angry, 1,400-lb. beast with 6-foot antlers, so give them a wide berth.

Moose (Photo: Dan Pierce on Flickr (CC BY-NC-ND-2.0))

Moose (Photo: Alex Butterfield on Flickr (CC BY-ND-2.0))

Moose (Photo: PLF73 on Flickr (CC BY 2.0))

Moose (Photo: Elliott Black on Flickr (CC BY-NC-2.0))

Red, White & Bluebird

“When nature made the blue-bird she wished to propitiate both the sky and the earth, so she gave him the color of the one on his back and the hue of the other on his breast.” —John Burroughs

Spotting a male eastern bluebird adds a special thrill to any outdoor excursion. Its patriotic plumage — vivid blue back, rusty red breast and white belly — makes it one of the most colorful animals in the natural world. Perhaps for this reason, it has the rare honor of being the official bird of two states: New York and Missouri.

While a treat for birdwatchers, the male eastern bluebird’s beauty has a more important function — to attract a female bluebird. To prove he’s a responsible mate, he takes some very rudimentary strides to build a nest in a tree cavity, often a hole created by a woodpecker. He spends most of his time perched near the hole, flapping his azure wings to “hook” an interested female. He leaves it entirely up to her to complete the housekeeping — gathering and fitting together the twigs and grasses to build the cup-shaped nest.

Once the 3 to 7 eggs in a typical brood hatch, the male helps feed the young. The normal bluebird diet consists of insects, fruits and berries, although they have been known to chow down on salamanders, snakes and tree frogs.

Unlike most bird species, eastern bluebirds typically hatch two broods a season. The first batch is pushed out of the nest in the summer. Those born in the second hatching tend to overwinter with their parents. Sadly Eastern bluebirds have a very high mortality rate — most die within the first year of life from starvation, freezing or falling prey to other animals. Still, their overall population has remained relatively stable.

How can you help Eastern bluebirds? If your yard is relatively open — they don’t like shady, forested areas — consider building a nest box. You can find tips for this here. And stop using pesticides: the bluebirds will take care of your lawn’s insects.

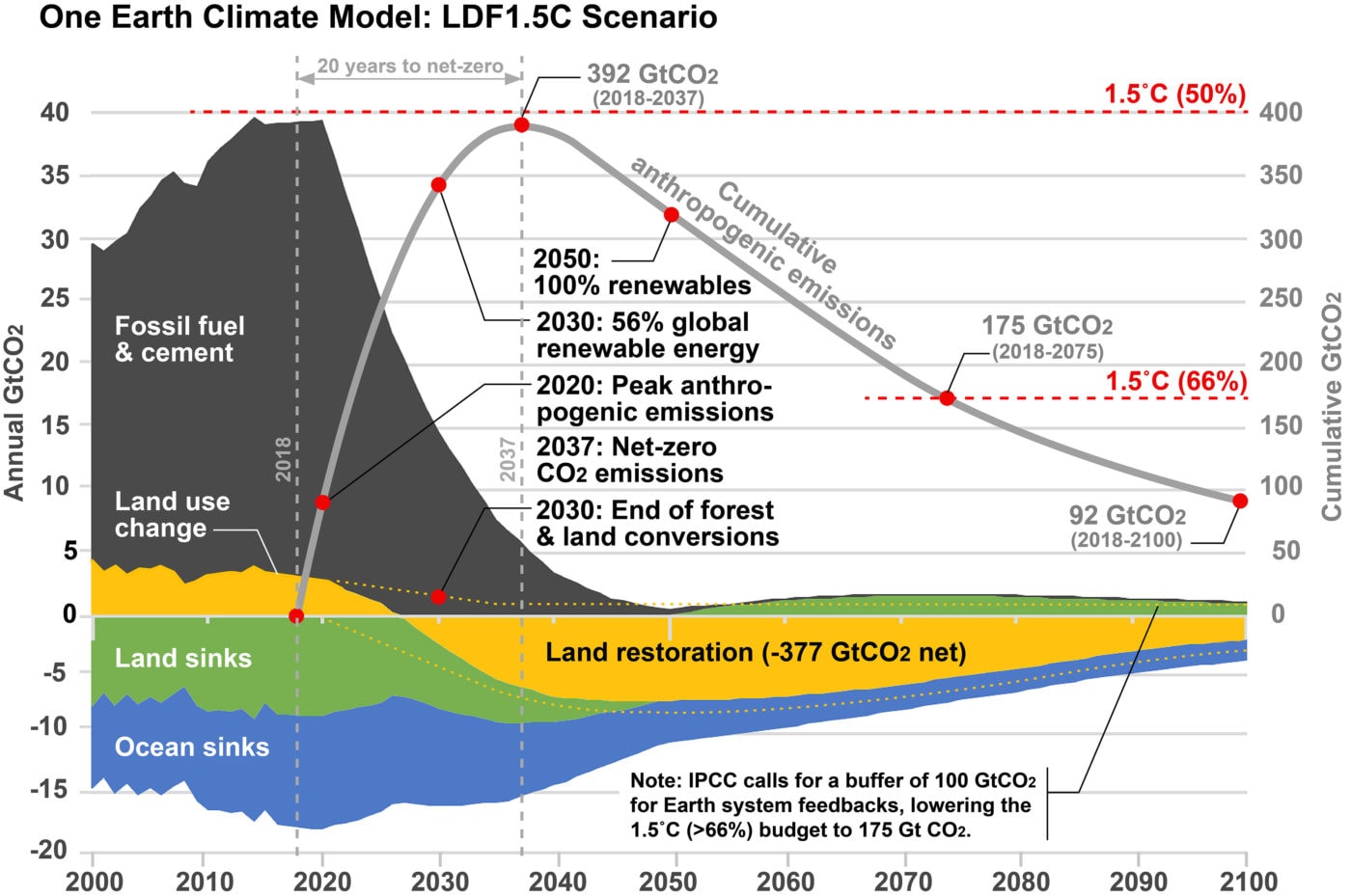

Global Deal for Nature

UN researchers estimate that 1 million plant and animal species face extinction. Meanwhile, January 2020 was the warmest in the 141 years of record-keeping. Hoping to roll back alarming statistics like these, a group of scientists have suggested making 30% of the planet a nature preserve by 2030, with an additional 20% to secure our terrestrial carbon sinks and promote climate resilience.

Their ambitious plan, called the Global Deal for Nature, has garnered wide-ranging support since its proposal last spring. Nearly 3 million people worldwide have signed a petition backing it, while several nations—from Costa Rica to Senegal—have begun taking steps to help reach the target.

But would it work? In terms of replenishing habitat, signs definitely point to yes. Animals don’t seem choosy about the lands they occupy, even if they have been degraded by humans. For example, in the decade since residents around the site of Japan’s Fukushima nuclear disaster were forced to leave their homes because of health concerns, more than 20 wildlife species—from Macaques to pheasants—have begun thriving.

“We know from many studies all around the world that when we give space to nature, she comes back spectacularly,” says National Geographic’s Enric Sala. “And we know that when nature comes back, all the services that nature provides for us come back, too.” Those services include sequestering carbon, which is essential for combatting the climate crisis.

The thornier question: Is the Global Deal for Nature doable? About 15% of the Earth’s land mass and 7% of its oceans are currently protected, so there’s a long way to go in a little time. And the forces lined up against its success—timber, large-scale commercial farming and mining industries (groups eager “to make money in the casino of the Titanic after hitting the iceberg,” according to Sala)—have deep pockets and powerful lobbyists.

Still, proponents of the Global Deal for Nature remain optimistic for the very reason that the planet’s future depends on it. “Even if [our energy system] went 100% renewable,” notes Sala, “we still need forests and wetlands and healthy ecosystems to help us absorb all the CO2 we’ve put in the atmosphere… There is no solution to climate without biodiversity.”

Smart City

Talk about sustainable urban planning: A Milan-based architecture firm has proposed a remarkable green development — 100% food and energy self-sufficient — on the 1,375-acre site of a sand quarry in Cancun, Mexico. The outside-the-box, planet-friendly concept would replace plans to build yet another shopping district in the tourist mecca.

Smart Forest City would include housing for 130,000 residents and habitat for 200,000 new trees, which works out to about 2.3 trees per person. And that marks just a small portion of proposed new greenery — a staggering 7.5 million plants of 400 different species. “Thanks to the new public parks and private gardens, thanks to the green roofs and to the green facades, the areas actually occupied will be given back [to] nature through a perfect balance between the amount of green areas and building footprint,” the firm says.

If constructed, the city will be ringed by arrays of solar panels and agricultural fields that can meet energy and food needs, respectively. Community amenities will be sited within walking or bicycling distance of all homes; if needed, vehicle transportation — whether on-road or via boat along a series of canals — would be all-electric, with traditional cars relegated to the outskirts.

Credit: The Big Picture

Credit courtesy of Stefano Boeri Architetti

Credit courtesy of Stefano Boeri Architetti

Bird’s-eye View

In addition to facilitating travel across the Hudson River’s Tappan Zee, the New NY Bridge offers a seasonal home to peregrine falcons. The state Thruway Authority provided a nest box for a couple of the endangered birds to raise their young. The box also offers a great high perch for them to spot prey in the river below. Falcons dive at speeds reaching more than 200 mph, making them the world’s fastest animal.

In addition to the box, the Thruway Authority kindly provided a camera that allows the public to play peeping Tom, keeping track of the birds’ comings and goings.