Driving along the distinctly suburban stretch of Route 17K in Coldenham, a hamlet in Orange County’s Town of Montgomery, it’s hard to imagine a time when this could have been “the habitation only of wolves and bears and other wild animals.” Yet that’s how Cadwallader Colden described the 3,000 acres of wilderness he acquired around there in the 1720s.

Colden turned some of this acreage into farmland and created ornamental gardens near the (long-demolished) stone mansion built for his family. That left plenty of habitat for trees and wildflowers, which Colden loved to explore. In time, he shared this interest with his daughter, Jane, whose zeal for identifying plants would earn her distinction as America’s first woman botanist.

Born in 1724, Jane Colden was fortunate to have a father who wanted her to do more than run a household, the common fate of most 18th-century women. That he steered her toward botany was not serendipitous: Despite a demanding “day job” as a high-ranking official in New York’s colonial government, Cadwallader Colden avidly pursued his study of plants. He provided the first scientific documentation of New York’s flora using the new system of classification developed by Sweden’s Carolus Linnaeus.

Colden shared his findings with botanists around the world. When queries from his correspondents became too time-consuming, he recruited Jane. Around 1754 she began documenting plants around the family estate, quickly earning her father’s praise. “[S]he is more curious & accurate than I could have been…her descriptions are more perfect & I believe few or none exceed them,” he admitted.

Soon, renowned botanists were writing her. Among those who admired her work were Benjamin Franklin and John Bartram, the father of American botany.

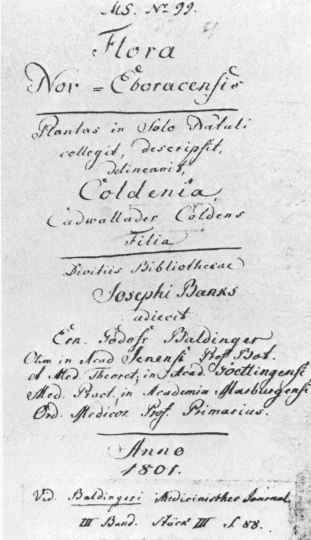

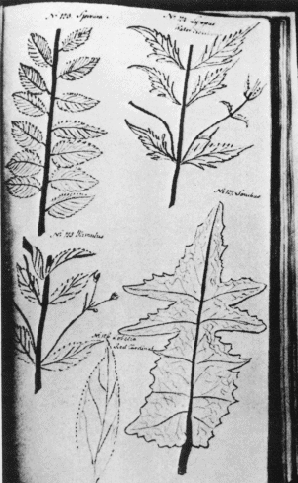

Going beyond identification, Jane sought out Native Americans to learn the medicinal and nutritional benefits of plants she “discovered.” She documented her findings in a manuscript containing written descriptions of 341 plants accompanied by 340 hand-drawn illustrations and leaf impressions. (It’s now in the British Museum’s collection.) She also shared her skills, perhaps most importantly with the young Samuel Bard, a future pioneer of American landscape design.

Throughout, Jane remained self-effacing about her talent. “You complasantly intimate that anything that I shall communicate to you, shall not be conceald,” she wrote a fellow botanist in 1756. “But this I must beg as a favour of you, that you will not make any thing publick from me, till (at least) I have gained more knowledge of Plants.”

Sadly, Jane Colden ended her studies in 1759, when she married. Even sadder, she died in childbirth 7 years later. For much of the next 200 years, her contributions were forgotten by all but hard-core botanists.

Over the last 50 years, the Garden Club of Orange & Dutchess County has worked hard to revive and sustain interest in this Hudson Valley pathbreaker. In 1963, it published a portion of her manuscript in book form. Later, it created a wildlife sanctuary at Knox’s Headquarters State Historic Site featuring native wildflowers identified in her manuscript. Most recently, in 2018 the club partnered with Bear Mountain State Park to build another garden filled with plants Jane Colden documented. Located near the park’s zoo, it helps to fulfill the wish of Peter Collinson, an English botanist who corresponded with Jane and later declared: “She deserves to be celebrated.”