Raise a tall glass (of water) to Poughkeepsie! Erin Brockovich’s new book, “Superman’s Not Coming,” calls for everyday citizens to speak up on community and environmental issues, including clean water. The famous activist highlights Poughkeepsie as an example of doing it right.

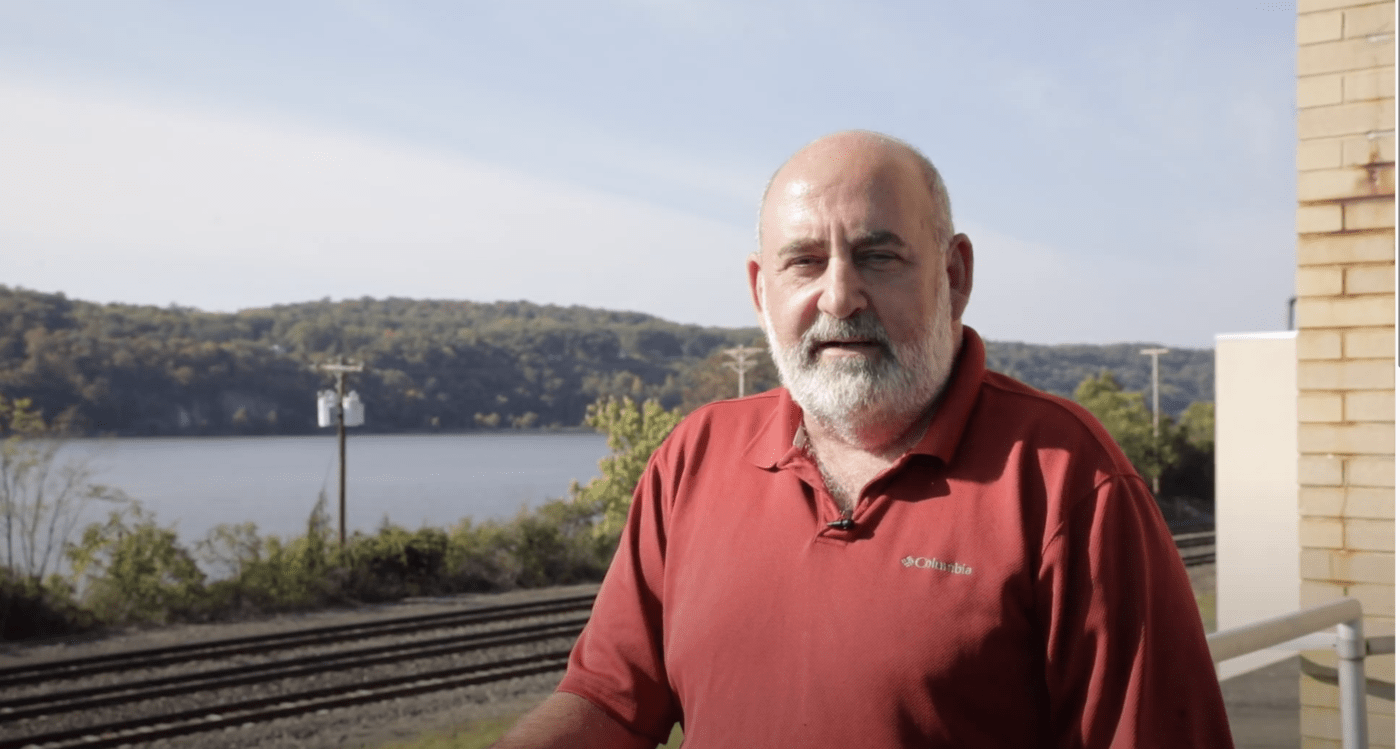

Brockovitch specifically praises Randy Alstadt, water plant administrator at the Poughkeepsie Water Treatment Facility. Alstadt, she says, acknowledged a water-treatment “fix” that was actually making things worse — and voluntarily corrected the process because it would be safer and healthier for residents.

Here’s how Brockovich and co-author Suzanne Boothby describe Alstadt’s experience in Poughkeepsie:

The plant started using chloramines, a mixture of ammonia and chlorine, in 2000 to help control the amount of DBPs (disinfection byproducts) in the water to meet EPA regulations. It was a cheap fix that only required a chemical feed pump, a chemical storage tank, and the cost of the ammonia. At the time, Randy said he was satisfied with the low-cost solution, and if he encountered any future problems, he would explore alternatives.

As soon as the water plant turned on the chloramine, they started to see increased corrosion activity in the distribution system, along with gaskets failing—both at the plant and in customers’ homes. Randy’s customers reported brown water coming out of their taps, no matter how many times he flushed the distribution system. Health problems, such as skin and respiratory issues, showed up too.

“Right when we made the switch, we had people calling and complaining about skin rashes and breathing problems, and they said their houseplants were dying,” he told me.

He was not aware of the health effects at that time, and to be fair, we did not have as much information then as we have today. These issues are consistent with what I’ve seen in so many of the communities that use chloramine today. The difference is that not all water companies seem to be as self-aware and honest as Randy. The water board approached him repeatedly, frustrated with the continuing rust and corrosion in the system as well as the customer complaints, so he hired an outside engineer to study the system and find a better solution. In 2010, he stopped using ammonia altogether.

“As soon as we turned off the chloramine, the brown water went away,” he told me. So did the health complaints. The problem with chloramine, Randy said, is that it masks the problem of organics in the water. It doesn’t get rid of them and it forms even more byproducts, which are currently unregulated. We certainly don’t need more unknowns when it comes to treating our water. Since then, the Poughkeepsie plant has approved funding and finished building a new $18 million system using ozone and biologically activated filters to help remove organic material from the water. The new system not only eliminates the need for chloramines but also reduces the amount of chlorine needed to clean the water.

Chloramines cost the city about $25,000 a year, so a new multi-million-dollar system was a big ask.

“It’s a lot of money, but if there’s one customer out there suffering because of my water, that’s not right. I don’t agree with that,” Randy said. “Nobody likes to hear that it will cost more than a million dollars to make upgrades. But I think that the health effects of chloramine don’t justify using it. Once the cost of the upgrade is divided amongst all the customers, the monthly increase is typically not that great. It turns out to be about the price of a meal per month. I let customers know it’s for better quality water, and people can agree to that.”

Randy says he’s a salesman as much as a water treatment operator. It’s all about doing what’s right to get the best quality drinking water to his customers. Think about paying $2 for a bottle of water when Randy can make clean water at a cost of $1 per thousand gallons. Which would you choose?

The new ozone system has been up and running in Poughkeepsie since October 2016. Randy says the disinfection byproducts have gone down to about a third to a half of what they were, depending on the time of year. That’s effective in reducing DBPs and exactly the kind of numbers any operator would hope for. In addition, using ozone has also helped him reduce the amount of chlorine needed to clean the water. While PCBs remain a concern in his area, he says he’s never detected them at the plant.

Randy makes it look easy. He has integrity and used his common sense to provide the safest drinking water possible to his customers. I applaud his efforts and I hope that Poughkeepsie can stand as a model for more cities and towns that are still weighing their options.

Watch Randy explain how Poughkeepsie cleans its water here: