Amid the brick and brownstone homes of Hudson, Nkoula Badila is teaching fellow residents within the city’s communities of color to sow seeds of green.

After launching a GoFundMe campaign in June, Badila’s community gardening initiative, Grow Black Hudson, shot past the initial $10,000 funding goal within 6 days. It amassed an extra $3,000 that’ll let organizers gather more supplies, plants and seeds. Thanks to this funding, plus in-kind donations, Badila and fellow community members have already set up up 17 raised-bed gardens and a handful of potted ones, with more to come.

Each extra dollar will help them operate beyond the next couple of growing seasons until they can become a nonprofit. The extra funding also helped cover the cost of acquiring the group’s car for transporting items.

Along with giving her another chance to indulge her lifelong love of nature, Badila rejoices at the pride felt by first-time growers — especially children — when they watch their tiny green sprouts develop into fresh tomatoes, ears of corn and other produce. She’s keeping things as broad as possible by introducing variety through veggies like kale, beets and eggplants, and fruits such as strawberries, raspberries and blueberries.

“It’s always like, ‘Oh word, you’re growing that [plant] right there! That’s gonna come through and then you can cook it,’ you know? We’re just making that connection — those vegetables they eat can be grown here and they get to do it,” Badila says. It’s that exact connection that Grow Black Hudson wants to cultivate among communities of color.

For Badila, that philosophy was intrinsically entwined with the practices her Congolese father shared with her and her 10 siblings while raising them in the Hudson Valley. Hudson’s small-town atmosphere and Badila’s Congolese roots melded into an adolescence she remembers as culturally rich, as she and her family shared songs, dances and artwork at many local school and theater programs.

Badila’s appreciation for nature was nurtured attending Ghent’s Hawthorne Valley Waldorf School, where she visited nearby farms and completed harvesting practicums. Her skills widened after she spent a few years post-high school WOOFing, or volunteering for an organic-farming exchange program in which can participants live and work at different partner farms around the world. Badila helped farm in Mexico, Colombia, Guatemala and other parts of Central and South America.

There’s no end goal with Grow Black Hudson as much as there’s an ongoing mission. It’s to build a deeper bond between people of color, agriculture, and all that land can offer — whether that be food, freedom, or just fresh air.

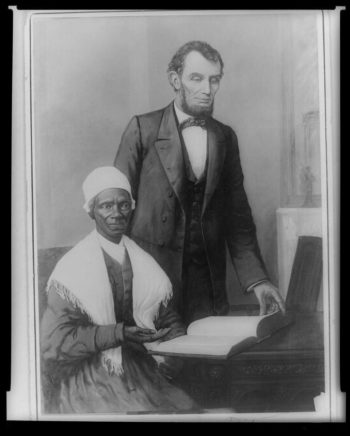

Before the Americas were colonized, the Indigenous groups that called the continents home maintained just that kind of relationship with the natural world. Colonial takeover beginning in the 1500s upended that, turning the relationship with the land into a transactional one that afforded wealth and status to those who had it, usually leaving out people of color.

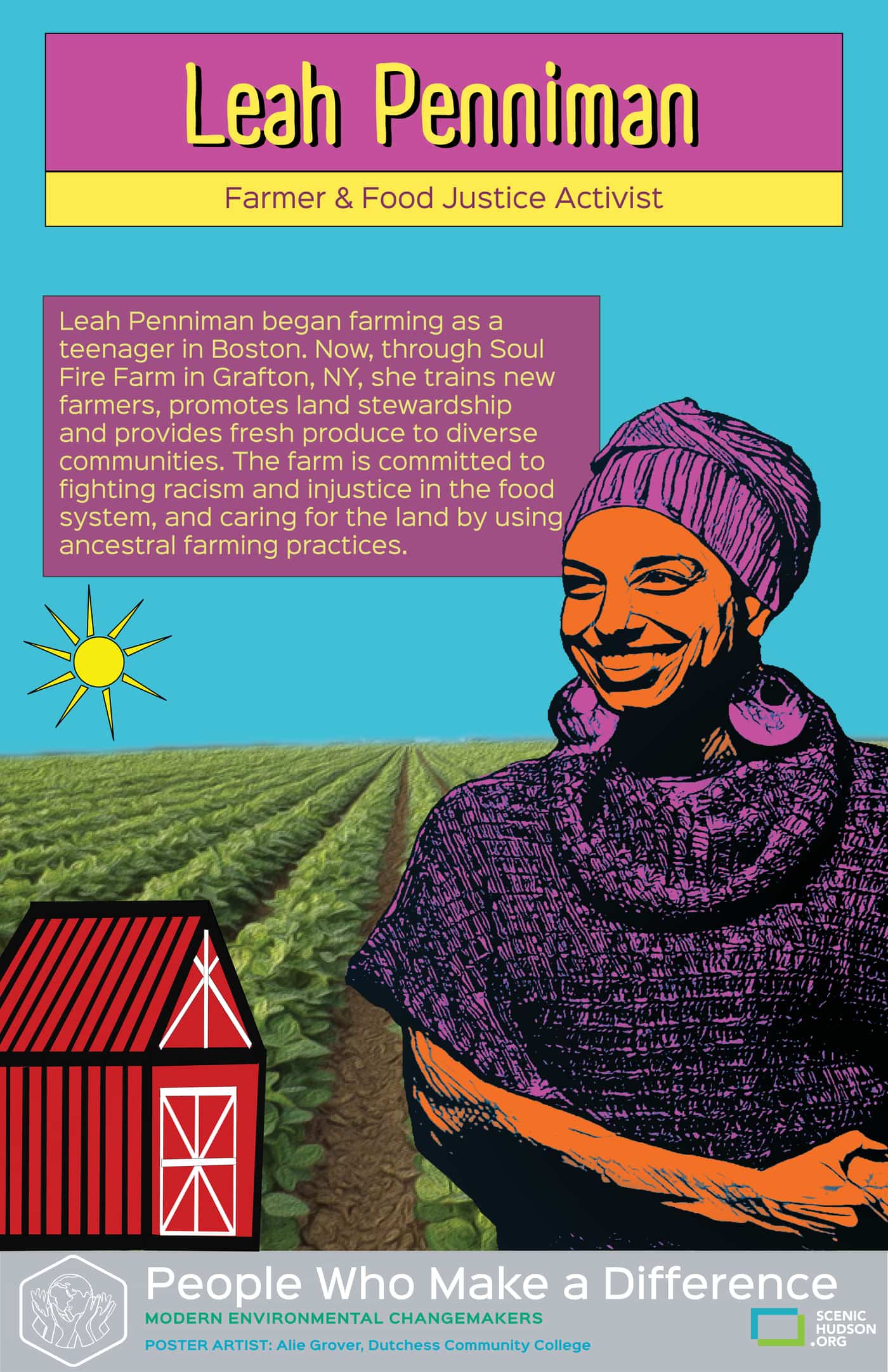

“For me, land is crucial to our ability to access our power and do for ourselves what they can’t,” Carmen Mouzon, a member of the board of directors at the Northeast Farmers of Color Land Trust, says. The Trust was started by Soul Fire Farms owner and educator Leah Penniman to combat the disparities that left nonwhites with only 2 percent ownership of all the farmland in the country.

Renewed calls to rectify history and systemic harms inspired by the protests following George Floyd’s death coupled with the mutual aid networks that appeared in numerous cities at the start the pandemic signaled to Badila that now would be as good a time as any for a homegrown initiative led by people of color, for people of color.

Badila channeled her energy toward food justice, and activists like Mouzon have been happy to see it. “People want to see that [type of project] where they are — rural or urban — and create that where they are,” Mouzon says.

The healing projects like hers could bring is twofold. Not only would it help resolve the complicated association with the land some Black Americans have due to the legacy of slavery and the subsequent period of sharecropping during the 19th and early 20th centuries, but it could also remediate the problem of food insecurity and related health issues that disproportionately affect communities of color the most.

“Especially with COVID[-19], I think people are seeing health a lot differently as far as how we can have a little more connection to natural healing,” Badila says. Aside from greater access to fresh fruits and vegetables, Grow Black Hudson participants will also have a chance to try the teas, tinctures and elixirs she’s making using the medicinal herbs like Saint John’s wort, mint and motherwort that also grow in the gardens.

Grow Black Hudson plans to expand into in-person workshops covering topics like food preservation in the coming weeks. Follow the organization and its progress on Instagram here.